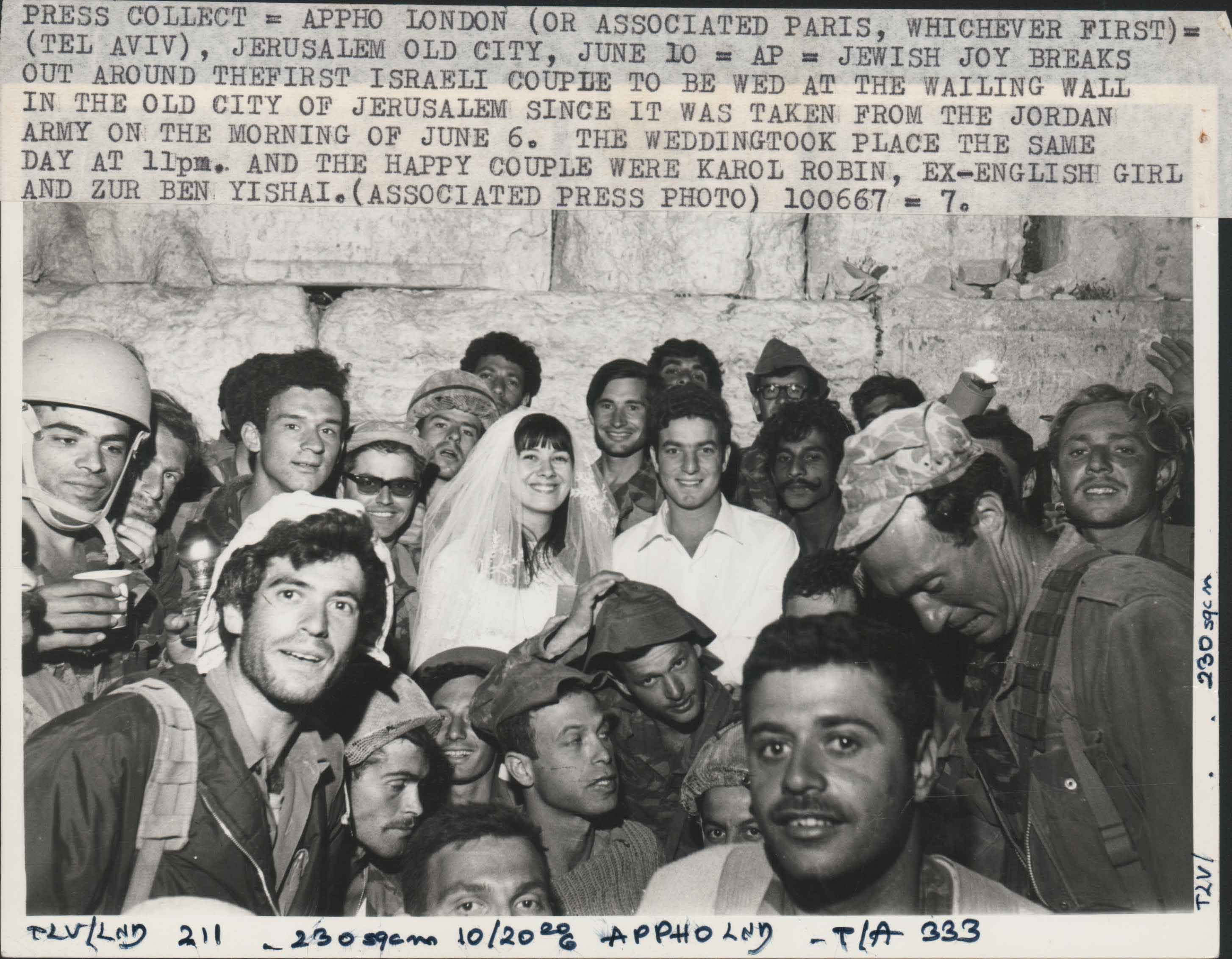

“…The realization of the age-old dream – the redemption of Israel”

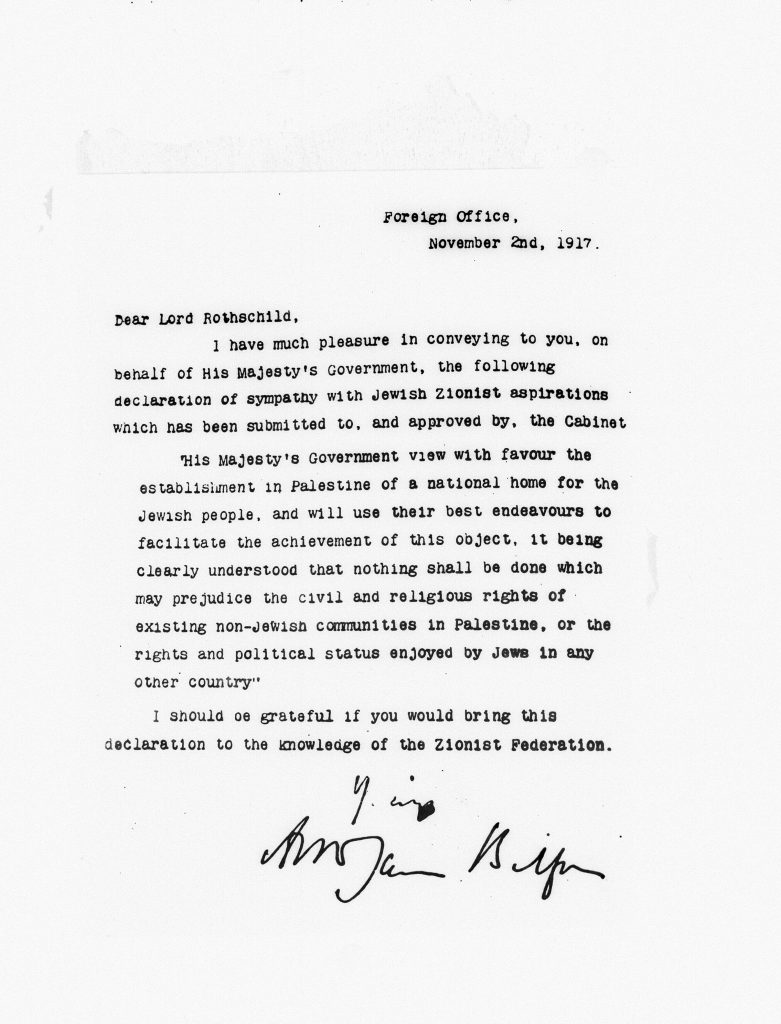

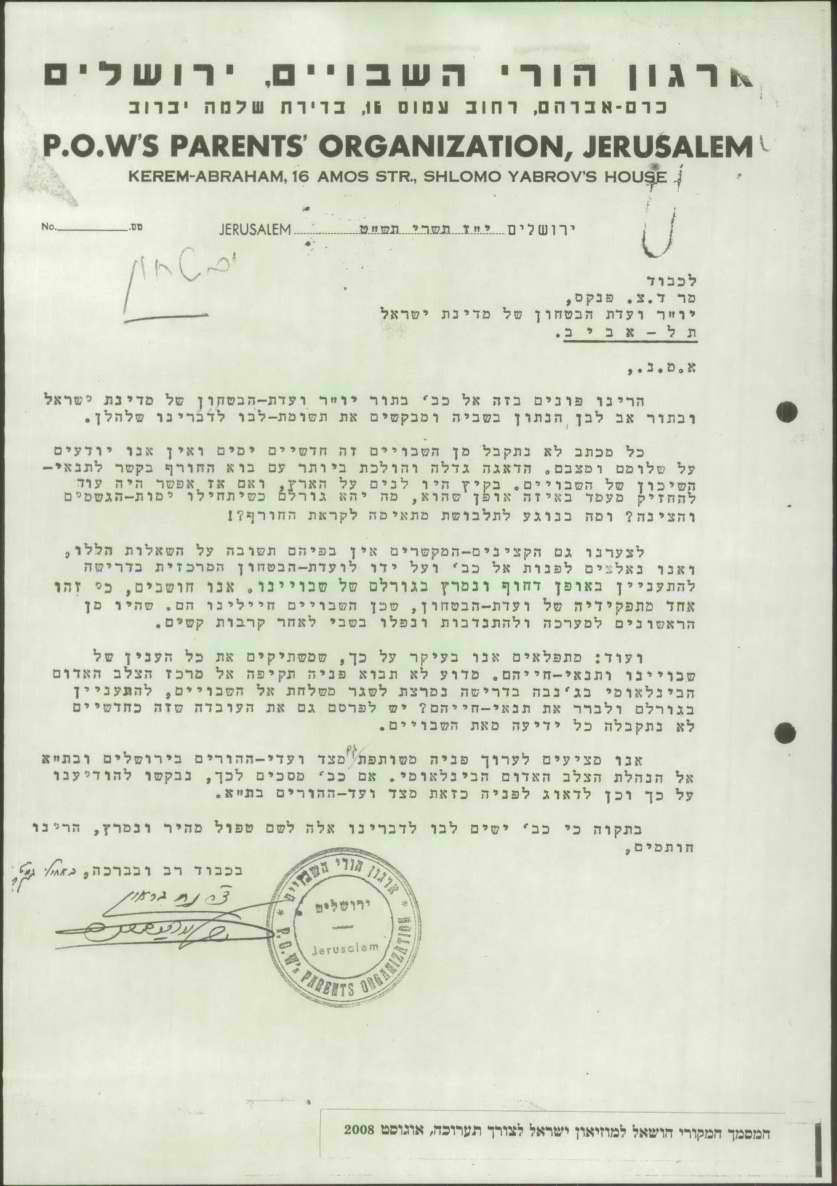

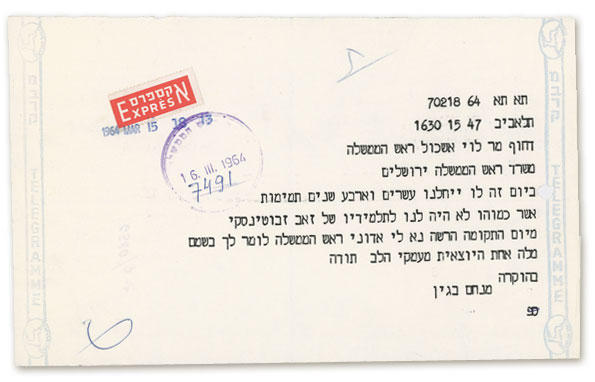

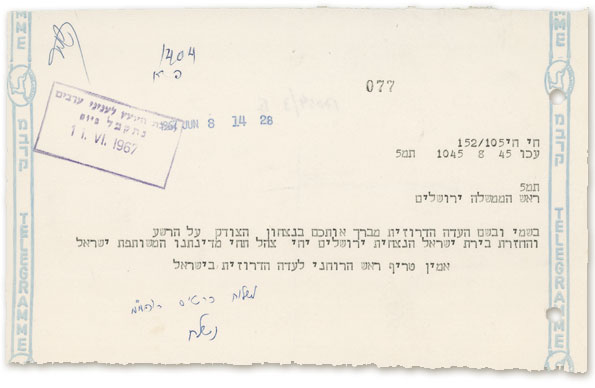

The Balfour Declaration

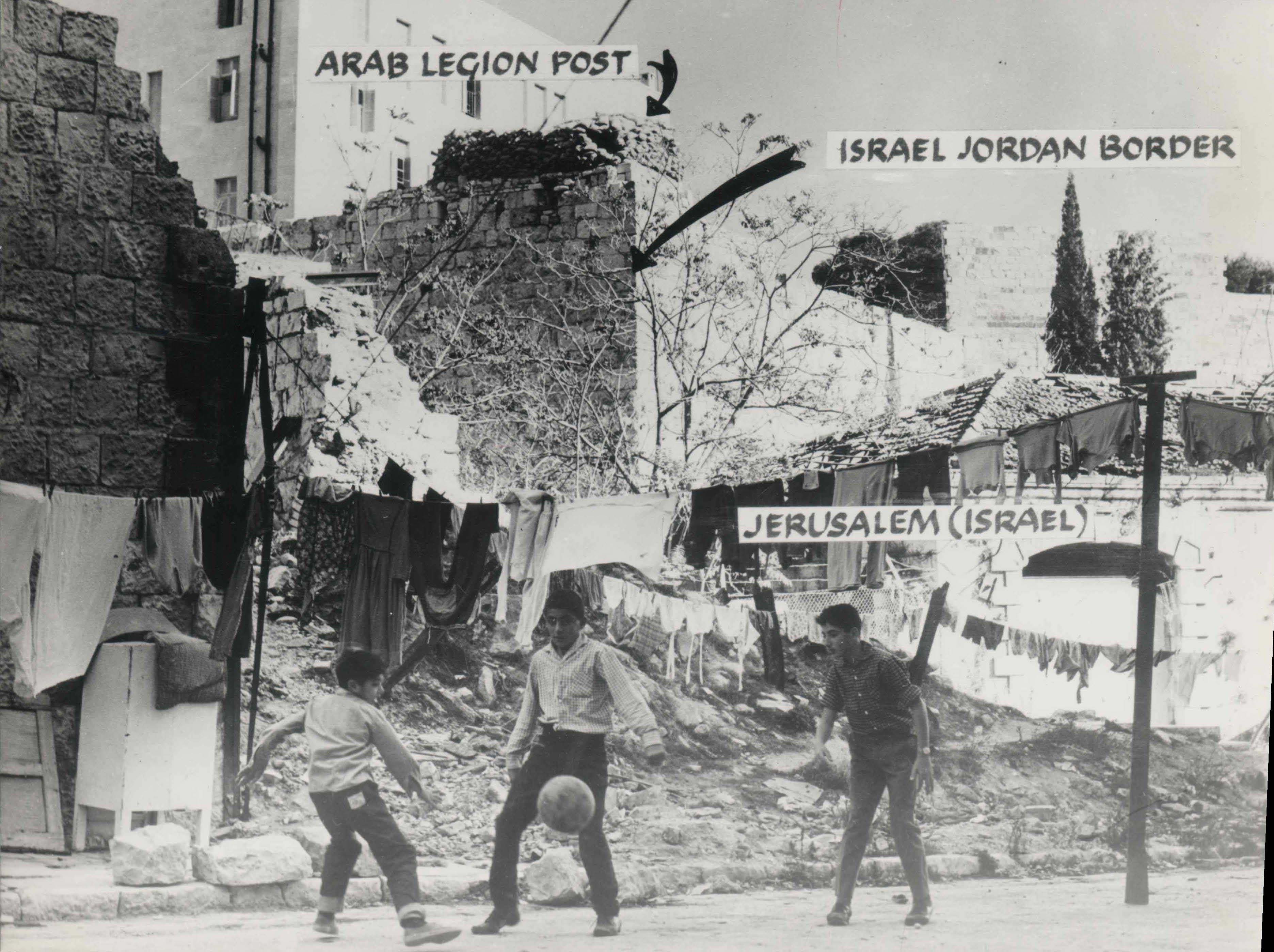

On November 2nd, 1917, the Foreign Minister of the British Government sent a letter to Lord Rothschild announcing the intention of the British Government to help establish a national home for the Jewish people. This declaration was ratified by the League of Nations at the San Remo Conference, which met on April 23, 1920, in which the British were granted the Mandate over Palestine (Eretz Israel).