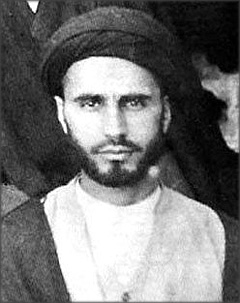

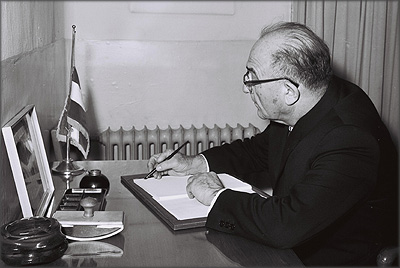

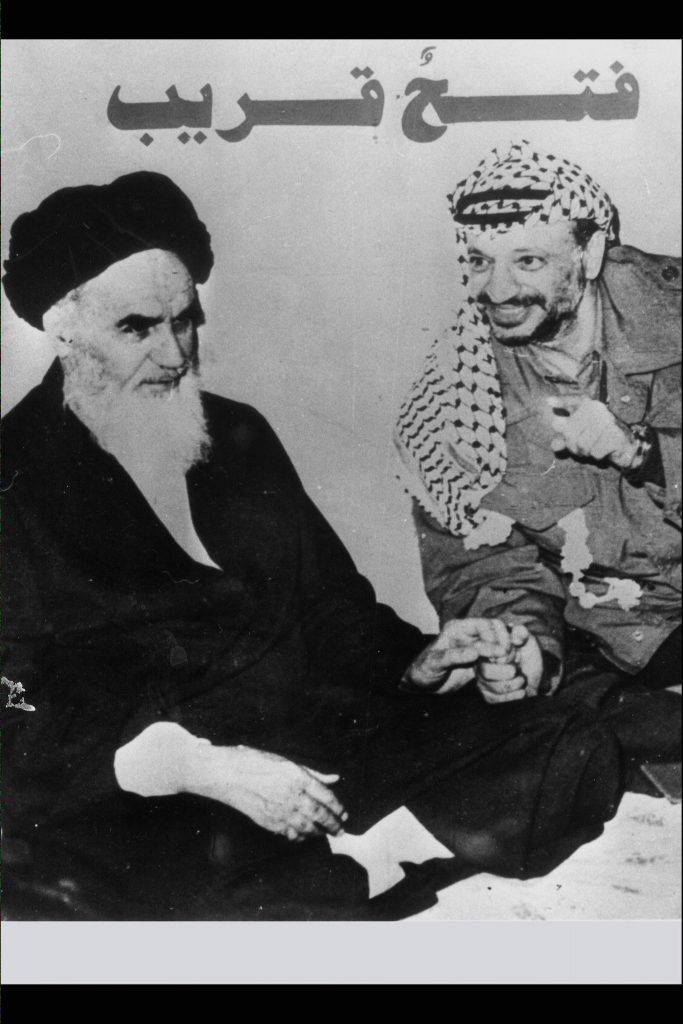

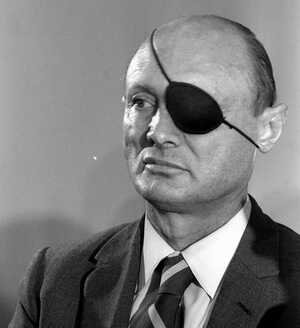

On 11 February 1979 Ayatollah Khomeini established a provisional government in Iran, beginning his effective rule of the country, which continued until his death in 1989 at the age of 87. The Islamic regime he established is still in power. Here the Israel State Archives presents a publication intended to shed light on the processes that brought Khomeini to a position of religious leadership in Iran in the 1960s, and to the establishment of the Islamic Republic at the beginning of 1979. It includes 47 documents, most of them reports from Israeli representatives in Iran and staff of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on the events in that country. These documents were declassified in 2014 for a special publication. Most of them are in Hebrew and are available on our Hebrew website. The English documents can be seen here.

The publication contains two parts: (a) Reports by Israeli representatives on Ayatollah Khomeini’s activities during the 1960s; (b) The Khomeini Revolution of 1978–1979.