Introduction: The Demand to Investigate the Yom Kippur War

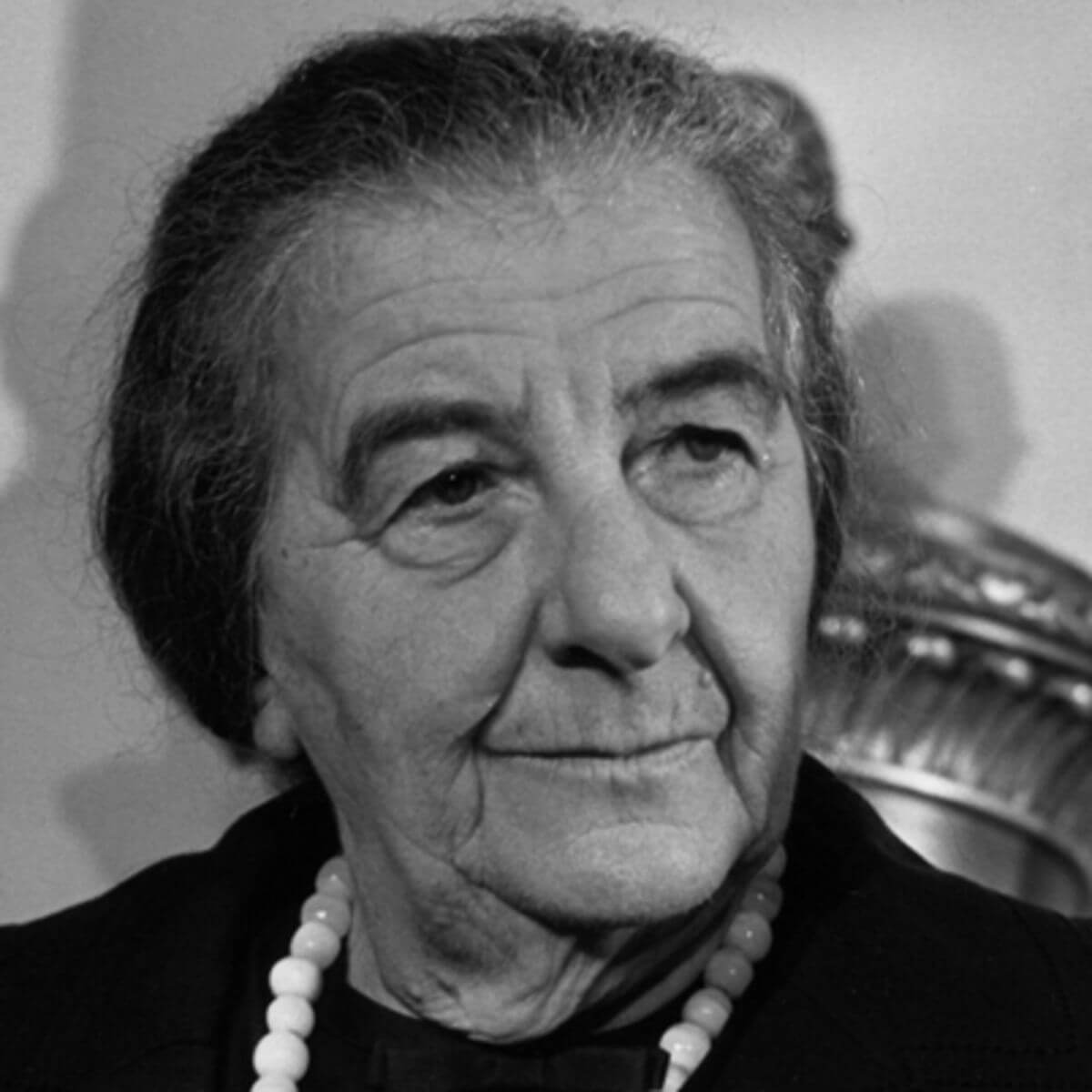

It was the night of 7 October 1973 in the Prime Minister’s Bureau in Tel Aviv. The Israeli government was meeting in a crowded room filled with cigarette smoke, at the end of one of the most difficult and frustrating days of the Yom Kippur War. The atmosphere was tense in view of reports on the situation at the front. Israel’s leadership seemed on the verge of despair. Frightening rumours were flying around and questions were raised about why Israel had been caught unprepared and why the reserves had not been called up. Minister of Immigrant Absorption Natan Peled asked why the reserves were called up so late: if the problem was lack of intelligence, then something had gone wrong. Golda Meir asked him angrily if he wanted the government to appoint a commission of inquiry immediately. This shows that as early as the second day of the war, the question of when and how to investigate the intelligence shortcomings preceding it and the insufficient preparations of the IDF was already in the air.

During the war the demand for an investigation came up again in Golda’s bureau, especially after the immediate danger had passed. For example, in the government meeting on 14 October, several speakers said that now the families of the fallen had been informed and the IDF was about to go on the offensive, previously suppressed public criticism of the government would emerge. They proposed a discussion in order to define their attitude in the coming storm. The prime minister said that there would be an investigation at the proper time, but it would be systematic and orderly, and “heads would not roll”. On 28 October she told the committee of newspaper editors that the matter was too serious and too painful to be solved by removing a few people from their posts. She herself was not sure who was responsible for the failure, but it should be properly investigated (See the record of the meeting, ISA, File A 7010/3).

As a result of the public pressure, on 21 November 1973 a commission of inquiry into the events leading to the outbreak of the war was set up, headed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Shimon Agranat. On 1 April 1974 the commission published a partial report calling for the dismissal of several of those involved and for institutional changes. The report led to a political “earthquake”, the resignation of Prime Minister Meir and the fall of the government, and to controversy which is still active today.

Many aspects of the commission’s work have already been published, but this is the first time that the dramatic government debates on setting up the commission and its findings appear in full. They show us what the ministers thought about the limitations on the commission’s authority and what they said about its failure to tackle the issue of the ministerial responsibility of the prime minister and the minister of defence. Here the Israel State Archives presents a selection of documents focusing on six stenographic records of government meetings published on our Hebrew website. The first two deal with the establishment of the commission, the next with the demand to widen its authority and the rest with the partial report and its findings.

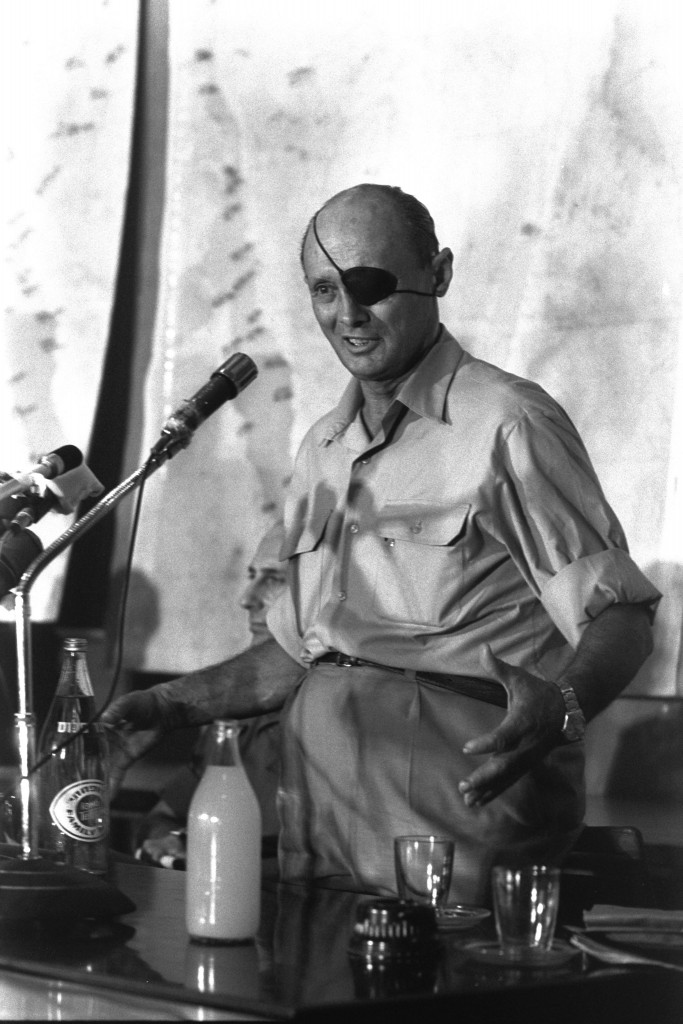

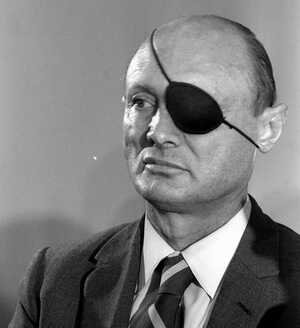

Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defence Minister Moshe Dayan and Minister Israel Galili visitng the Southern Command in the Sinai, 29 October 1973. Photograph: Yehuda Zion, GPO