“…re-establish themselves in their ancient homeland…”

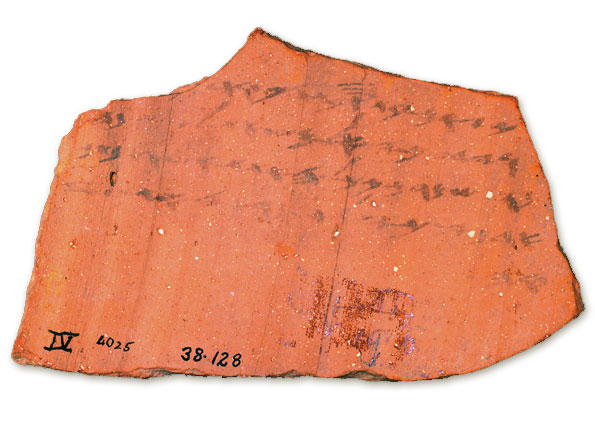

Ink on pottery 586 BCE

This letter, written in ink on pottery, may be one of the most poignant expressions of the dramatic final moments of the biblical Kingdom of Judah. The ostracon was part of the archive of letters discovered at the gates of the city of Lakhish, shortly before its destruction at the hands of Nebuchadnezer, King of Babylonia in 586 BCE. The potsherds were found beneath a floor covered in ash, a sure sign that the site had been destroyed by fire. The final sentence of the letter reads as follows: “For we are watching the Lakhish fire signal; according to the signs which my lord has given, because we do not see Azeqah.”

According to the archaeologist Yigael Yadin, this sentence tells us that that the torches of Azeqah, a neighboring city to Lakhish, had been extinguished; in other words, Azeqah had already been captured by the Babylonians, but the defenders of Lakhish were still determined to persist in the struggle for their own city. The prophet Jeremiah, who was calling at the time for Judah to surrender to the Babylonians in order to save Jerusalem, described the events in the following words: “When the army of the king of Babylonia fought against Jerusalem, and against all the cities of Judah that were left, against Lakhish and against Azeqah; for these fortified cities remained of the cities of Judah.” But not long after these words were spoken, Lakhish was conquered and destroyed, and soon after that, Jerusalem was razed and the First Temple was burned to the ground.

Letter, discovered in the ruins of Lachish, relates that the torches of the neighboring town, Azeqah, were extinguished, meaning that it had been captured by the Babylonian army. Lachish itself was conquered shortly thereafter, and in the same year Jerusalem was taken and the First Temple destroyed. These events are also described in Jeremiah 34:6.

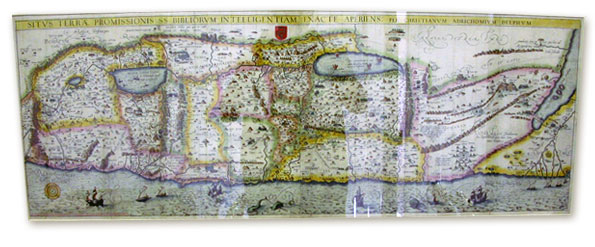

The territorial boundaries of the Tribes of Israel on both sides of the Jordan River

Christian van Adrichom was a learned priest from the Dutch city of Delft who worked in Cologne, Germany. He produced this map for his comprehensive work Theatrum Terrae Sanctae, in which he surveyed the Holy Land, and delineated its division among the tribes. The map is oriented to the east, and extends from the cities of Amalek and Petra in the southeast, to Mount Hermon in the northeast. To the west is “the Great Sea,” namely the Mediterranean. A depiction of the Prophet Jonah being thrown to the “Big Fish” appears among the sailboats and legendary sea monsters. The coastline runs from the Nile Delta in the south to the city of Sidon in the north. As in the Madaba Map, the southern part of the coastline runs almost straight and does not curve as it should. This is probably a function of the rectangular format of the map. The boundaries between the tribes are marked by hatched lines, highlighted in color. More than 800 sites and events are marked or portrayed on the map. The miniature illustrations represent scenes that span the period from Cain and Abel till the 6th century CE. They include biblical scenes as well as traditions borrowed from the New Testament and the Apocrypha. The illustrations are meticulously drawn by a master artist, and they give the map a captivating storybook flavor.

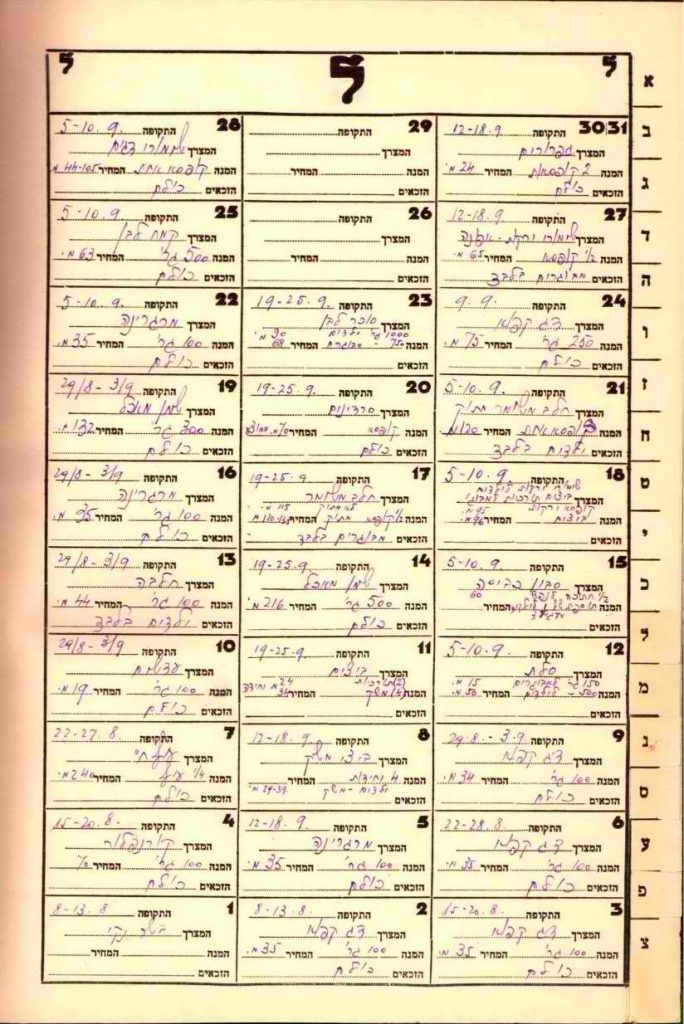

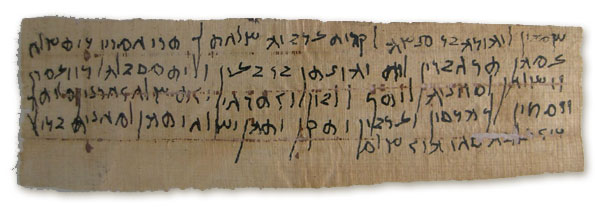

Bar Kokhba Revolt and the Sukkot festival

The following letter was sent in the heat of the battles of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, in which Jewish fighters battled the legions of the Roman Empire. In the end, the revolt turned out to be one of the bloodiest calamities in Jewish history. The letter was apparently sent by the leader of the revolt, Shimeon son of Koziba – better known by his nom-de-guerre, Bar Kokhba – to Yehudah son of Menasheh.

In this letter, he demands that “palm branches and citron” and “myrtle branches and willows” be delivered to the camp, apparently in order to enable the camp dwellers to properly celebrate the Sukkot festival. Four Species are used for Sukkot – lulav (date palm frond), etrog (citron), hadasim (myrtle), and aravot (willow).

This papyrus document is just one of the many letters discovered in the Judean Desert Cave of the Letters – a most remarkable treasure trove of archaeological finds. Here a small number of Jewish rebels evidently lived and died. They were most likely high-ranking participants in the revolt.

Letter sent during the Second Revolt against Rome, 132- 135 CE.

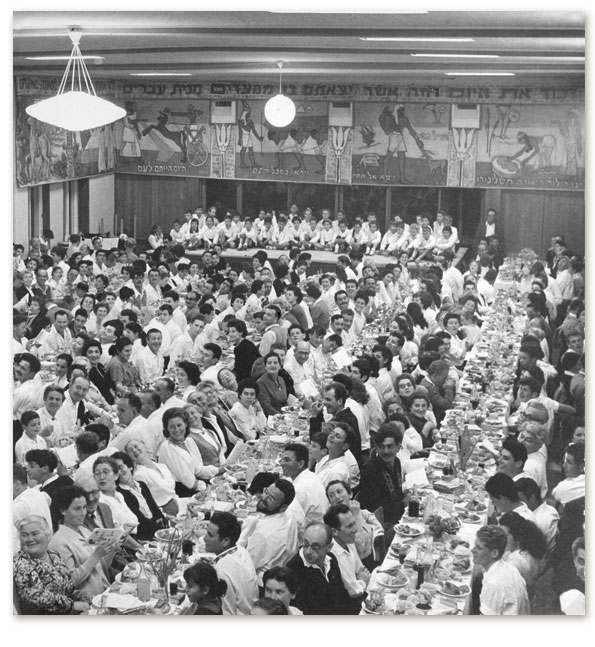

Passover Seder night at Kibbutz Mishmar Ha-Emek 1958. Photographer: Nahum Tim Gidal

“…the eternal Book of Books…”

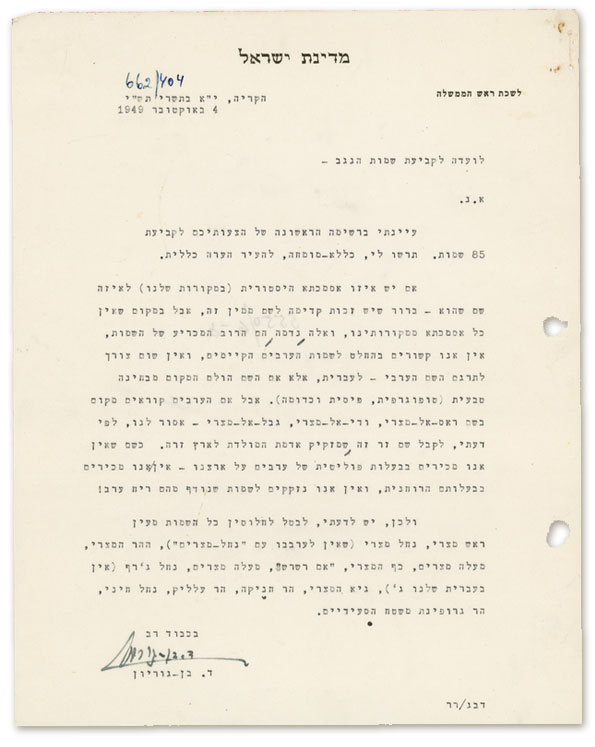

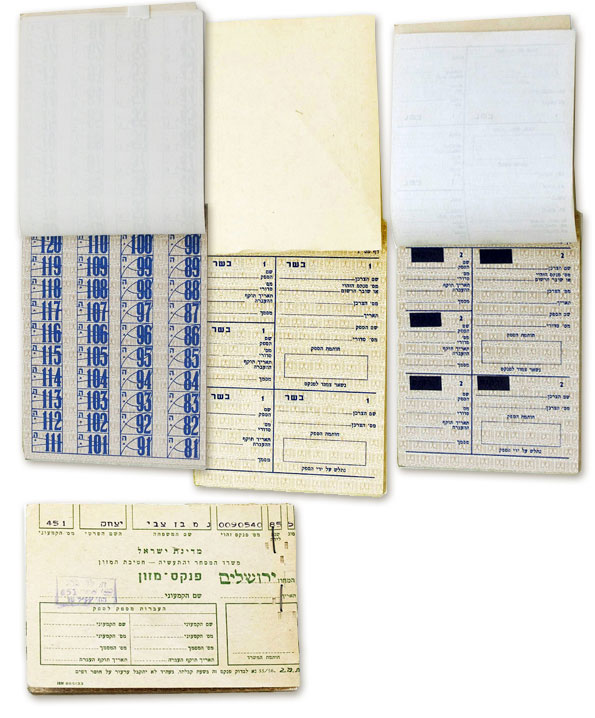

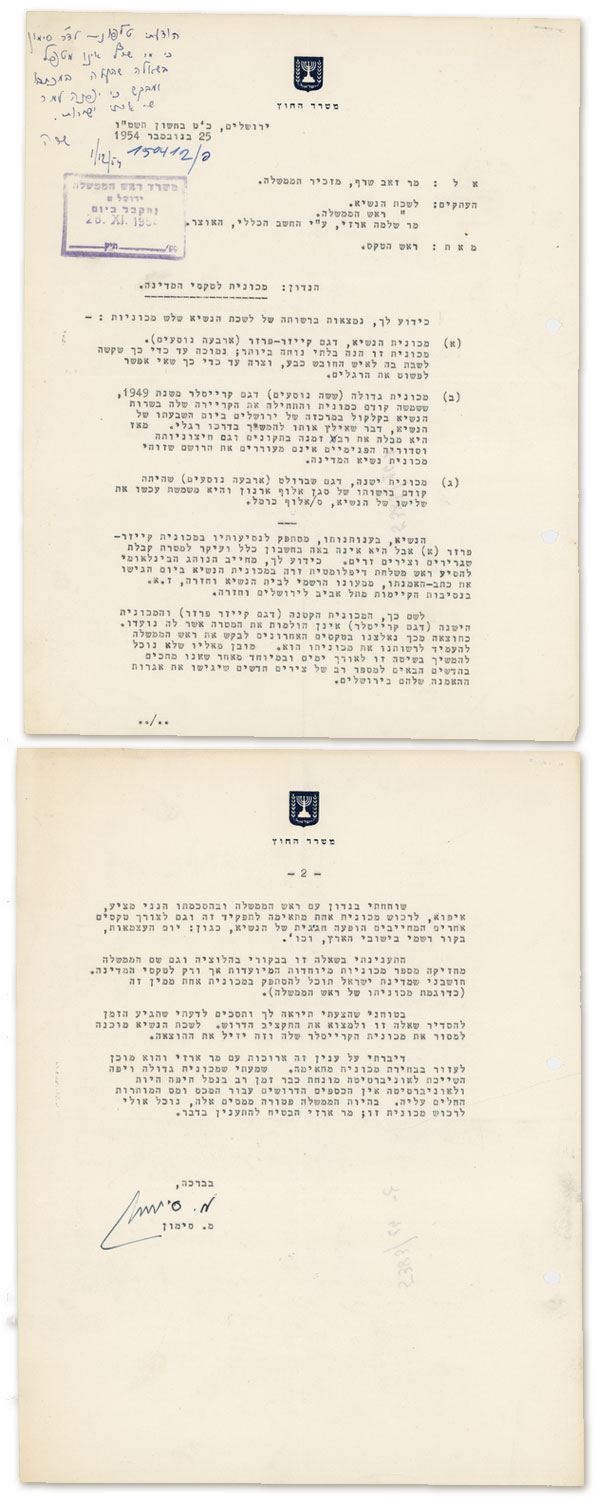

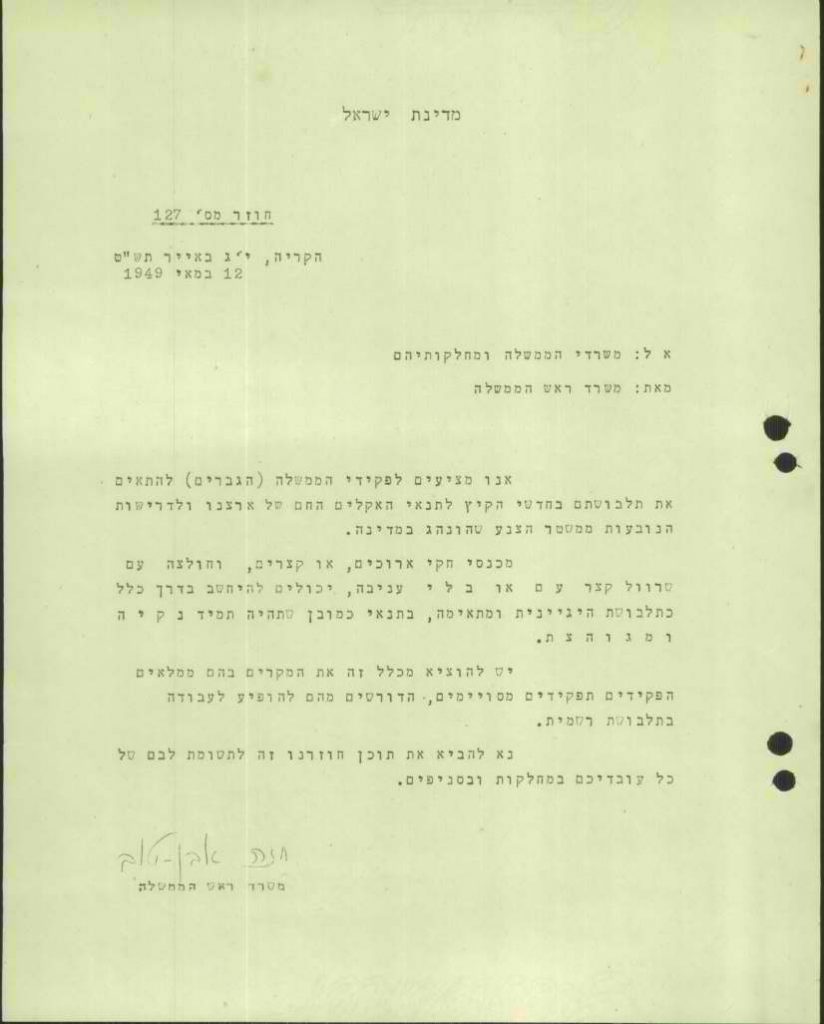

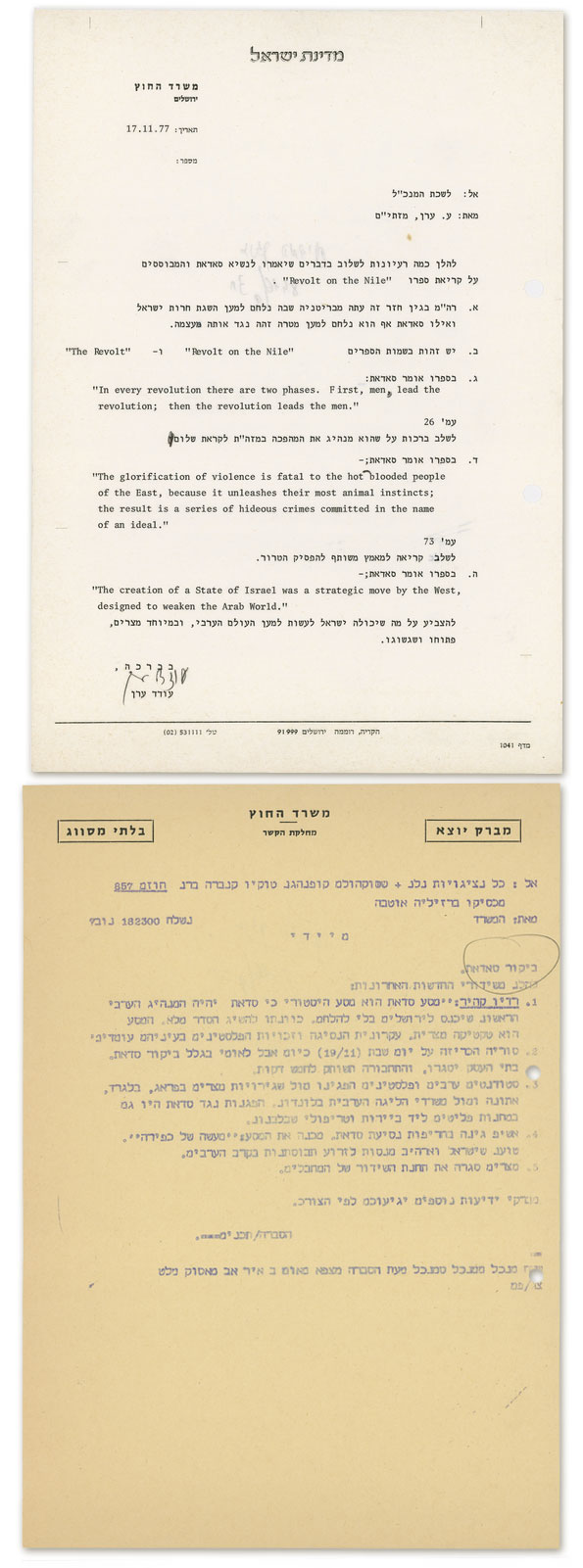

Smuggling the Aleppo Codex into Israel

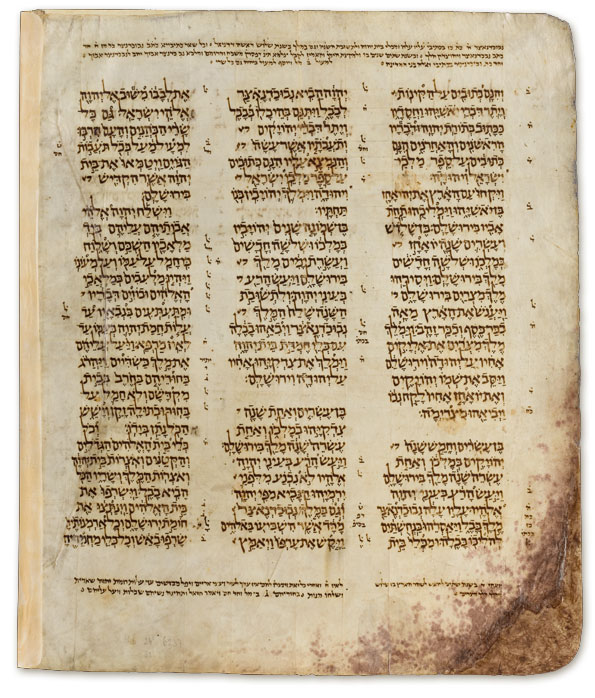

The Aleppo Codex is the oldest known manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. The unique qualities of this manuscript make it one of the most important Hebrew documents, and one of the most invaluable sources for biblical research. The Codex was probably written in Tiberias around the year 920 CE. From there it was taken to Jerusalem and then to Cairo, where it was cited by Maimonides in his discussion of rules for writing a Torah scroll. In the early fourteenth century, it reached the Syrian city of Aleppo. There the manuscript was kept in a special case in the synagogue and guarded for hundreds of years by the heads of the local Jewish community.

Following the UN vote calling for the Partition of Palestine on November 29, 1947, violent riots erupted in Aleppo, and the Great Synagogue housing the Codex was set on fire. When it was found that the Codex was damaged but not destroyed, discussions were held with the leaders of the Jewish community in Aleppo. Attempts were made by a number of people in Israel, most notably Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, to produce an arrangement whereby the Codex would be moved to Jerusalem. But it was not until the summer of 1957 that the Codex was finally smuggled from Syria to Israel through secret channels. So as not to endanger members of the Jewish community in Aleppo, the arrival of the Codex in Jerusalem was kept a strict secret for some time, and it could be studied only by a select, privileged group of researchers, prominent among them, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. In May 1962, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and Meir Laniado, a representative of the Aleppo community, co-signed a document referred to as a “Bill of Trust” for the Codex, at the rabbinical courthouse in Jerusalem. The Ben-Zvi Institute was chosen as the permanent home for the Codex. Later the Codex was transferred for safekeeping to the Israel Museum. It is housed in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum till this day, but it remains the property of the Ben-Zvi Institute in accordance with the Bill of Trust.

This page from the Aleppo Codex, discovered in New York in 1981 and delivered to the Jewish National and University Library, was entrusted to the Ben-Zvi Institute and is exhibited here by decision of the Board of Trustees of the Aleppo Codex and the Small Codex.

Page from the Aleppo Codex (Chron 2 35:7-36:19), Tiberias, Land of Israel, 10th century Manuscript

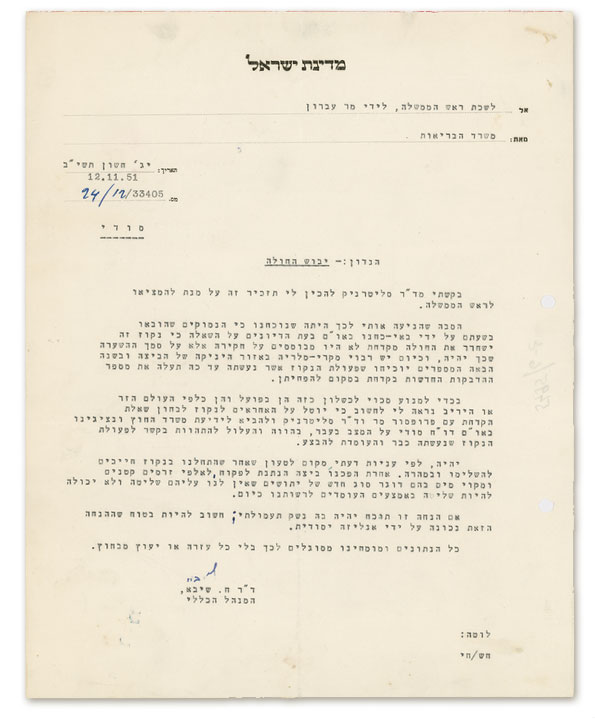

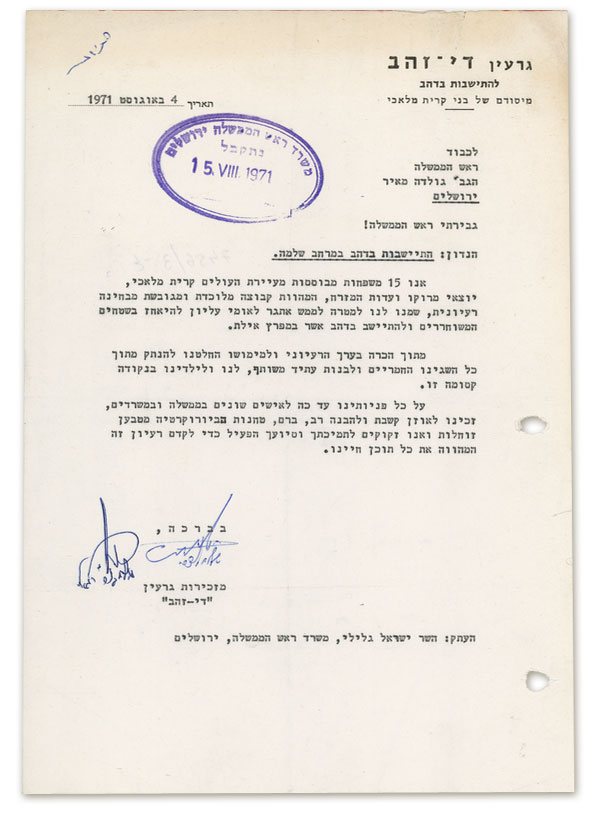

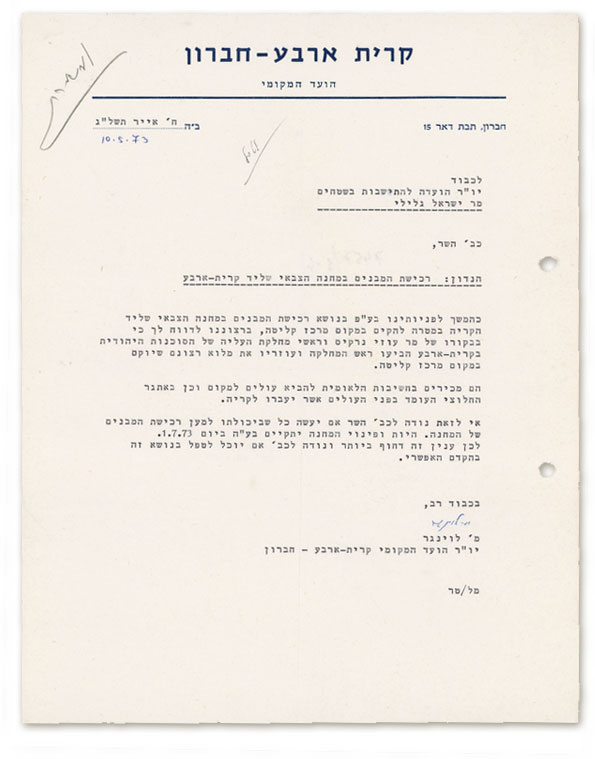

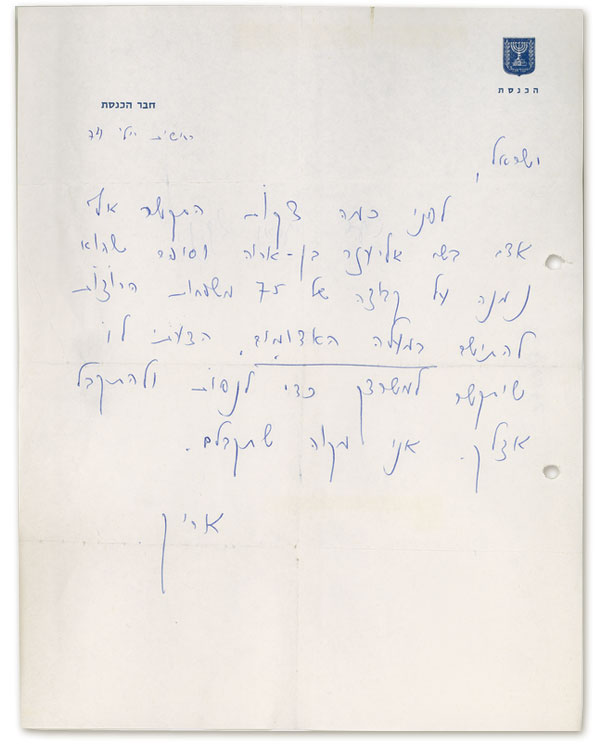

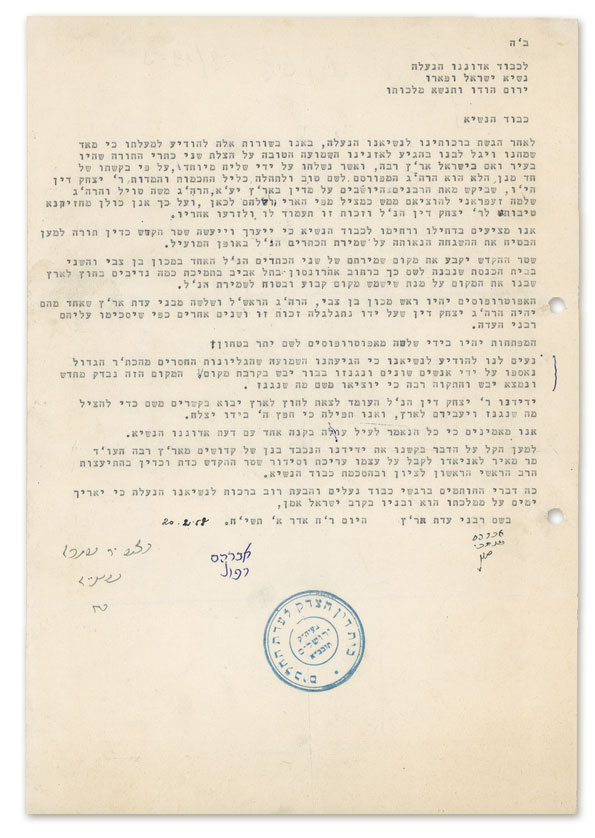

Letter announcing the arrival of the Aleppo Codex in Israel, and giving the details of the ownership procedures that apply – procedures that are in force till this day

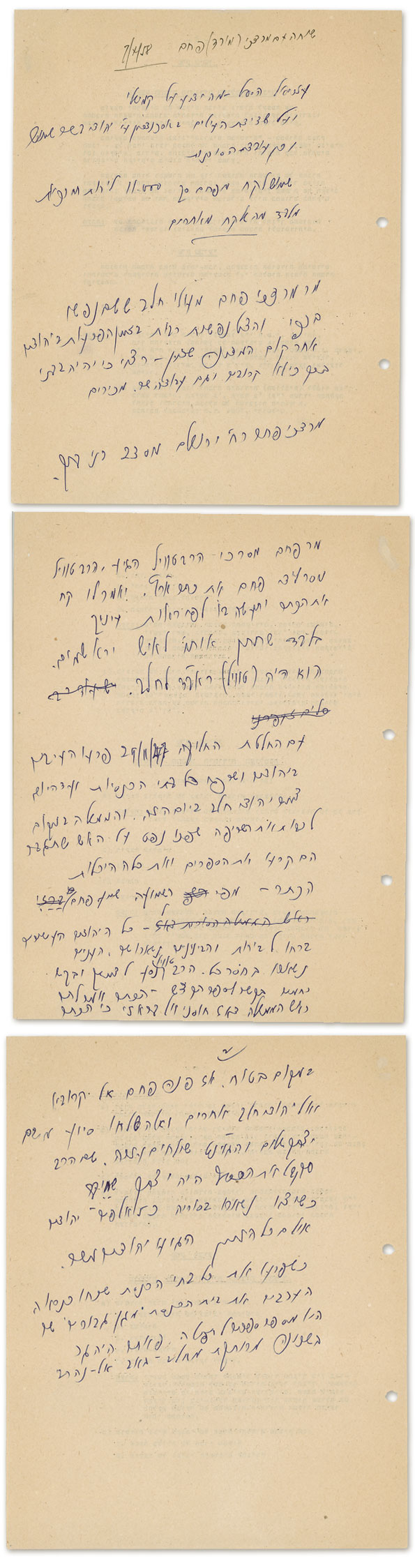

Testimony of Mordecai Murad Faham, a Jew who smuggled the Aleppo Codex into Israel, recorded in writing by President Izhak Ben-Zvi,1958