Revolution in Iran and renewal of negotiations with Egypt, February 1979

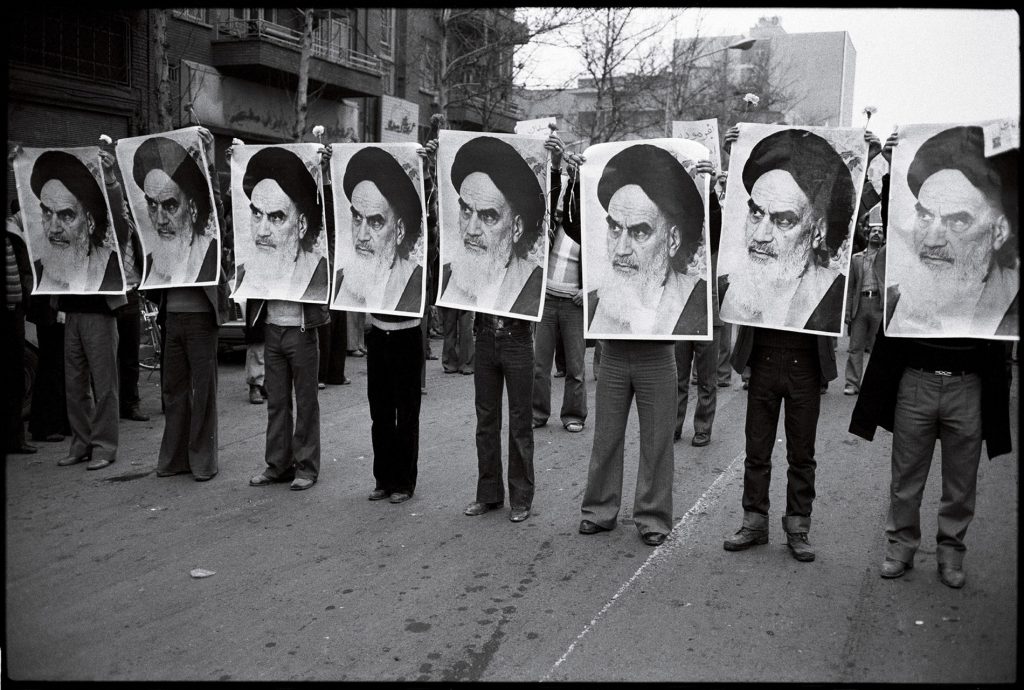

Row of demonstrators holding Khomeini’s portrait, Iran, 1978. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Meanwhile the attention of the world had turned to Iran. During 1978 the Shah’s regime had lost its hold and by January 1979 some government authorities had ceased to function. Riots were organized by religious bodies led by Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini from his place of exile in Paris. On 16 January the Shah left Iran. On 1 February Khomeini returned to Teheran and on 11 February he deposed the prime minister, Shapour Bakhtiar, and set up an Islamic republic (See the ISA publication on Ayatollah Khomeini’s rise to power). These developments had an important influence on the peace process between Israel and Egypt. The Islamic regime was hostile to the US and Israel and cut off relations with them. Carter wanted to tie Egypt more closely to the US and to prevent the spread of the revolution, and Egypt’s role as a moderate force in the region became even more important. However Israel, now cut off from Iranian oil, needed a substitute source of supply and also feared the fall of the regime in Egypt, as had happened in Iran.

Although Brzezinski still hoped that Israel would make concessions on the Palestinian issue in order to obtain Saudi support, feeling was growing that the US might need to go ahead without it. The Israelis felt that the US had not pressurized Saudi Arabia enough. On 5 February Dayan held a consultation in the Foreign Ministry. David Ofek, an expert on the regime, explained that as an oil-rich country with a weak army, Saudi Arabia felt it was essential to preserve Arab unity and not to take sides with either camp in order to preserve its stability. Sadat, in taking his initiative and signing the Camp David accords, had acted without consulting them. At Baghdad they had attacked the accords but not the diplomatic process. Sadat’s attacks on Prince Fahd had caused their position to harden. The Saudis were worried by the undermining of the Western position in Iran, Yemen and Africa by Libya, Iraq and other radical forces and felt that the US response was inadequate. The Saudi press was deeply critical of the US over Camp David, but they would not endanger their alliance with it. Some of those present proposed a discreet attempt to weaken the image of Saudi power in the US. Meir Rosenne criticized the hypocrisy of the Administration in glossing over Saudi human rights abuses. However Dayan said that he was more concerned with Saudi influence on Egypt. Undermining Saudi relations with the US would not help Israel, which could not serve as an alternative to the Arab world, and if possible, the Americans should not be forced to choose between them (Doc. No. 70).

By now Carter had decided on a final effort to wrap up the talks, and he sent a letter to Begin saying that the best answer to the revolution in Iran was to complete the negotiations on the peace treaty. He proposed that Dayan, Vance and Khalil should meet again at Camp David on 21 February. “It would be a tragedy if we failed to complete the journey which began with President Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem” and Begin’s response to that visit (See Document No. 71). Carter hoped that again the isolation of Camp David might help to break the impasse. If the talks were successful he would hold another summit. A similar letter was sent to Sadat. Begin agreed to send Dayan.

On 11 February Israel’s new ambassador in Washington, Ephraim Evron, wrote to Dayan, surveying the aims and positions of the Administration. Congress and public opinion alike agreed that “peace between Israel and Egypt is the most necessary thing for the West in general and the United States in particular at this moment”. Carter badly needed a foreign policy success. Evron warned that Vance and other senior officials believed that Begin was trying to evade setting up autonomy in view of internal opposition, since they thought that the issues holding up the treaty were not really serious. But if Israel concentrated on its essential interests, the climate in the US was favourable to a deal. If the talks failed, Israel would be blamed. (See Document No. 72).

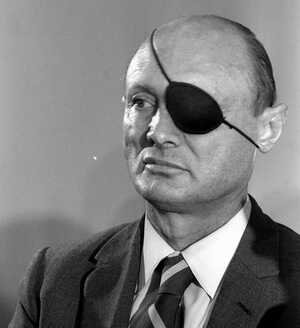

U.S. Defense Secretary Harold Brown with Defence Minister Weizman at Ben-Gurion airport, 13 February 1979. Photograph: Moshe Milner, GPO

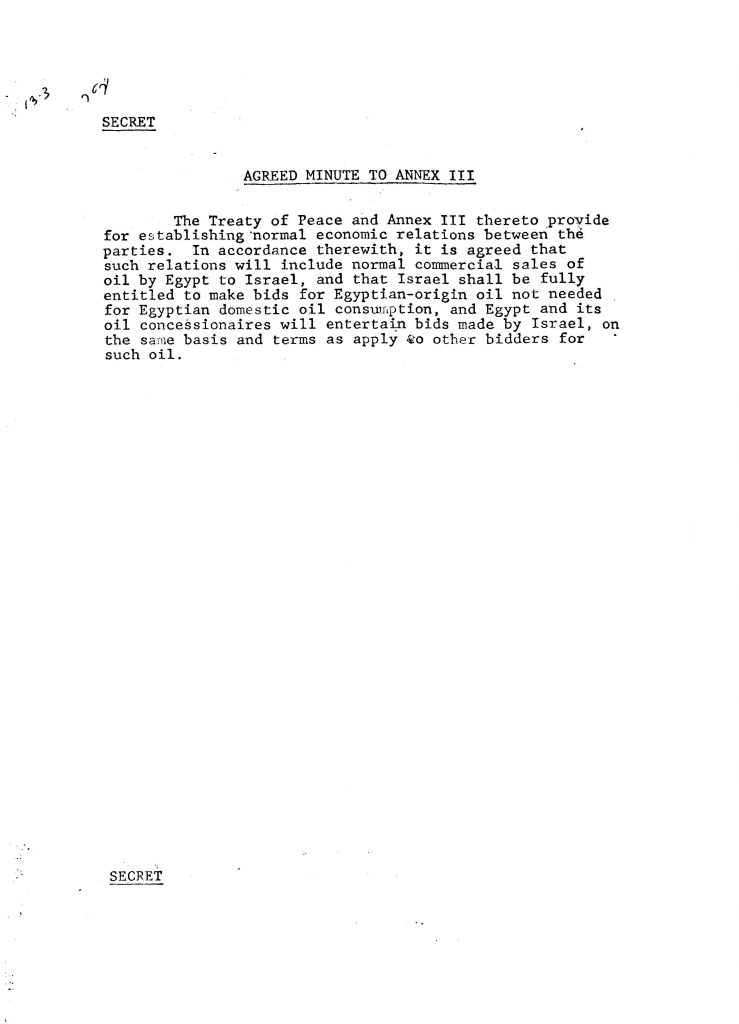

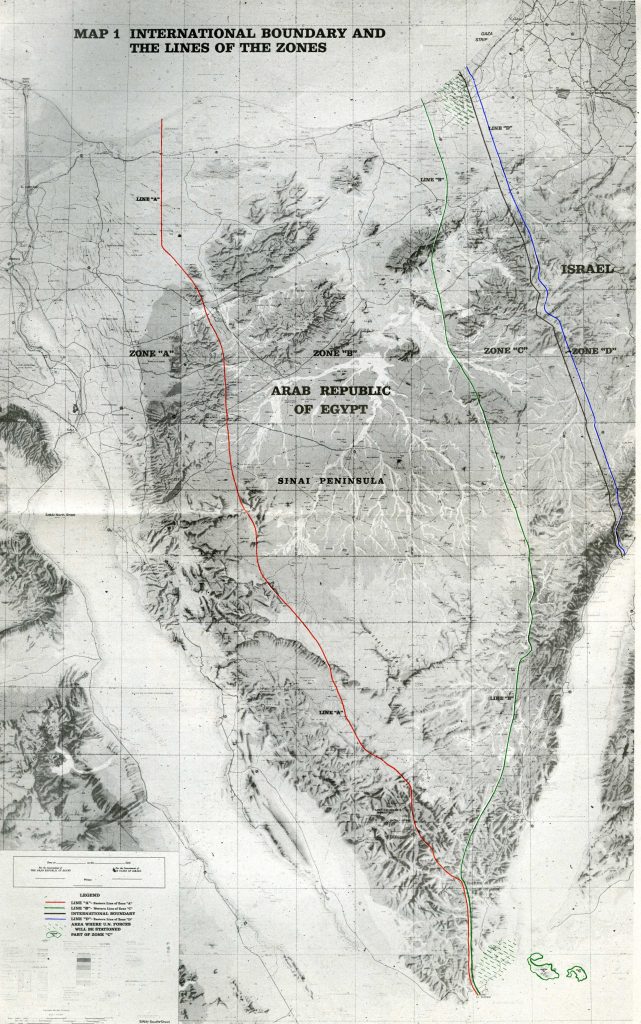

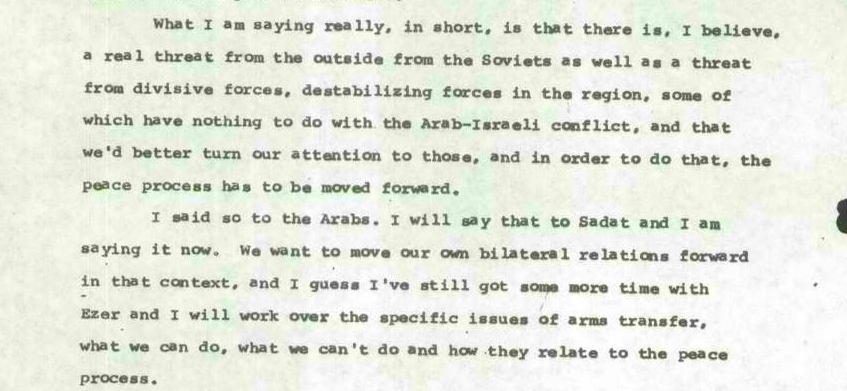

Since he had lost Begin’s confidence, Dayan was pessimistic about prospects for the talks, even though he had received a message from Boutros Ghali, saying that Egypt wanted to sign the treaty as it was worried about unrest at home. 90% of the questions in the treaty were settled and they hoped to settle the remaining ones at Camp David. This message was not sent directly to Israel, since there was no direct channel with the Egyptians after Weizman had left the talks. (Tamir and Magdub too had left Washington in January after settling almost all the details of the Military Annex). However Weizman took part in the talks with Defense Secretary Harold Brown, who visited Israel in February as part of a tour to shore up US allies in the Middle East. Brown made it clear that the US would oppose an overt attempt by the Soviets to interfere in the Middle East but the countries of the region must act to prevent encroachment via proxies such as the Cubans. Dayan expressed fears about the stability of the Egyptian regime and the fate of US arms if it fell, and asked if the US could take over the Israeli bases in Sinai rather than Egypt.

Extract from the stenographic record of Dayan and Weizman’s talk with Brown, 14 February 1978. ISA, File MFA 6914/5, p. 114