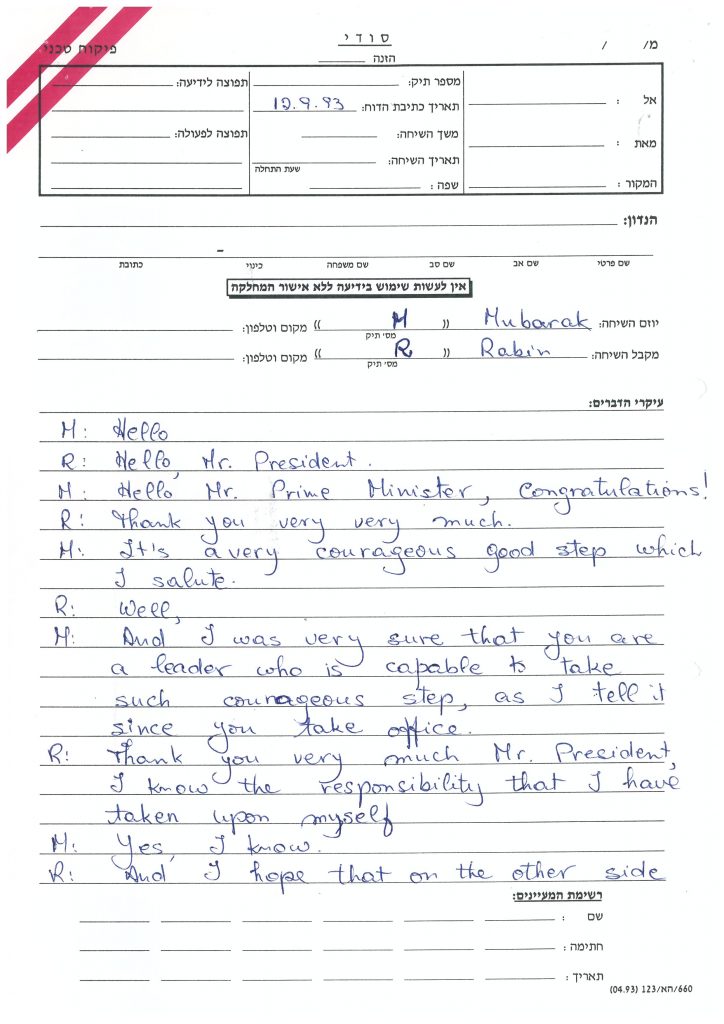

ב.1 | Reaction to the Oslo Agreement

On September 13, 1993, Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Abu Mazen (Mahmud Abbas), representing the PLO, signed the “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements” (“Oslo I Agreement”) at the White House in the presence of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, PLO chairman Yasser Arafat and US President Bill Clinton. Secretary Christopher witnessed the agreement with the representative of Russia, and Rabin and Arafat shook hands.

For details of the negotiations on the Declaration of Principles, see “The Road to Oslo” publication.

For the full text of the Declaration:

The main points included:

- establishment of an interim Palestinian Self-Governing Authority

- IDF withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho within six months of the entry into force of the agreement (October 13, 1993)

- elections to a Palestinian National Council within nine months of the entry into force of the agreement

- fixing a five year transition period until the permanent agreement. This period would begin with the withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho. Negotiations on the permanent settlement would open two years after the withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho. The issues discussed would include controversial subjects such as Jerusalem and the refugees.

- the Autonomy Council would first be given authority in Gaza and Jericho and later throughout the West Bank, excluding issues to be discussed in the permanent settlement

- a strong Palestinian police force would ensure internal order. Israel would continue to be responsible for the security of Israelis, residents of the settlements and protection from external threats

- cooperation at the crossings between Gaza and Egypt, and between Jericho and Jordan. Israel would continue to control security at the crossing points

- the elections to the Council would be conducted under international supervision.

Appendices to the agreement included arrangements for economic cooperation and regional development

Recognition of the PLO and the agreement signed with it, which reversed previous government policy, took the Israeli public by surprise. There was a gulf between those who supported the Declaration of Principles and its opponents, mostly from the Likud and other Opposition parties. Labour movement members, who had settled in Judea and Samaria under the policies of the Alignment governments, also feared the future. Although jurists had ruled that the prime minister was not obliged to bring such agreements to the Knesset, Rabin decided to seek its approval. On September 21 he presented the agreement to the Knesset, highlighting the prospect of a new era of peace. He made it clear that Jerusalem and the Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria and the Gaza Strip would remain under Israeli rule, and the IDF would be responsible for security. The authority of the Palestinian Authority would not apply to Israelis. Despite fierce protests from Opposition leaders, the Knesset approved the agreement by a majority of 61 coalition members to 50. Eight Shas members and three Likud members abstained.

Excerpts from Rabin’s speech in the Knesset

Given the deep concerns raised by the agreement in national religious circles and among the settlers, on September 22 Rabin met with the leaders of the moderate religious Meimad movement, Rabbi Yehuda Amital, one of the heads of the yeshiva in Gush Etzion, and Dr. Yehuda Ben-Meir, a former Knesset member. Rabin repeated his commitment to protect the settlements during the period of the interim agreement and agreed that the defence establishment would consult with the settlers on their status and security (Document 3, Meimad Leaders’ Meeting with Yitzhak Rabin, 22 September 1993).

Palestinians celebrating in the streets of the Old City of Jerusalem after the first Oslo Accord, 20 September 1993. Photograph: Avi Ohayon, GPO

There was also fierce opposition to the plan within the PLO, especially from Farouk Kaddoumi, head of the PLO political department, who saw it as surrender to Israel. Supporters of the agreement highlighted the achievements of the Palestinians in bringing Israel closer to recognizing their sovereignty. For the first time, Israel had agreed to discuss in the permanent agreement negotiations issues it had previously refused to consider, such as Jerusalem, the future of the settlements and refugees. They argued that Israel’s agreement to withdraw to defined boundaries implied sovereignty (Document 1, Danny Rothschild to Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres, 2 September 1993).

A document in the Hirschfeld Collection sheds light on the attitude of the Hamas to the agreement. On September 14 Ephraim Lavie of the Advisor on Arab Affairs Department in the Civil Administration met with the head of the movement, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, in his cell at the Ashmoret Prison where he was serving a sentence of life imprisonment. The sheikh claimed that as an Islamic leader he had legitimacy that Yasser Arafat did not, and opposed recognition of Arafat as the exclusive representative of the Palestinian people. However Hamas would not act to thwart the agreement by force. He expressed willingness to participate in the elections and government under certain conditions, for example a complete Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank. The Intifada would continue because Arafat has no control over it. (File P 5517/1). And in fact, the PLO’s opponents, and especially the Hamas movement, supported by Iran, intensified terrorist attacks.

Border Police and demonstrators against the Accord outside the Prime Minister’s Office in Jerusalem, 8 September 1993. Photograph: Avi Ohayon, GPO