א.1 | Progress and internal disagreements

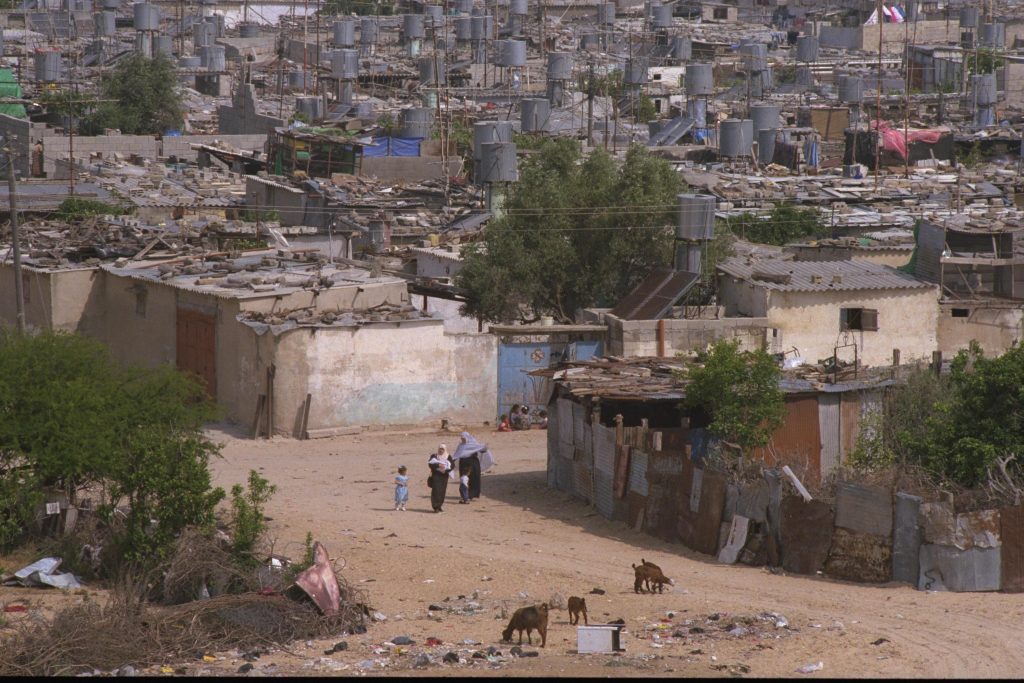

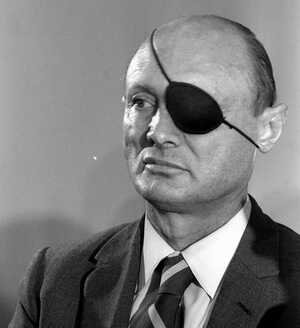

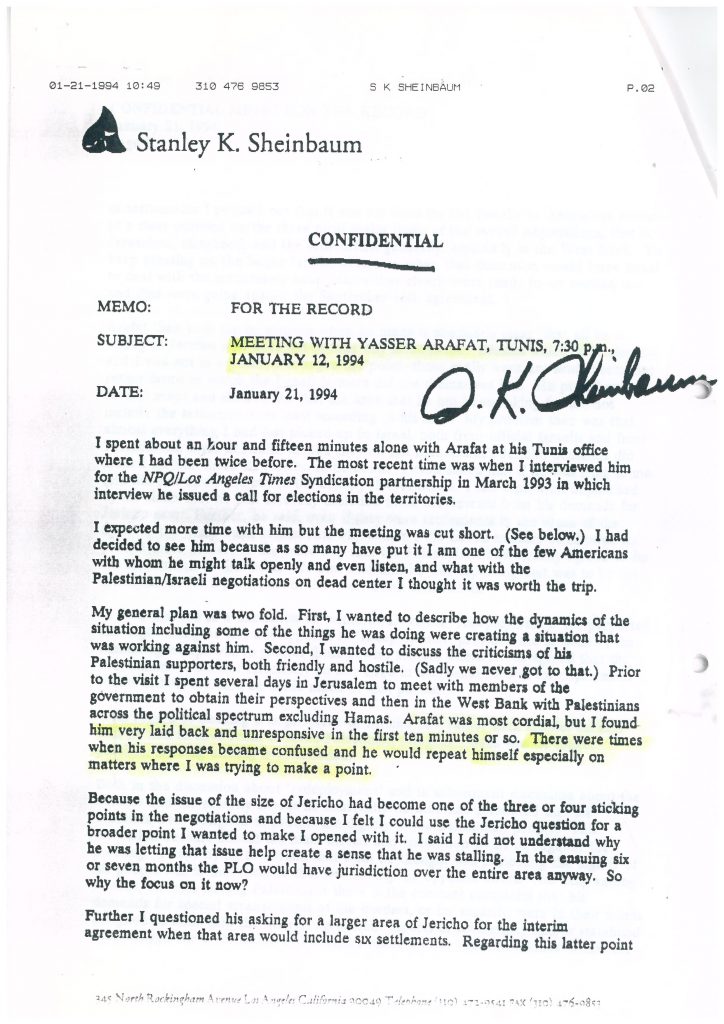

Talks with the PLO in Taba resumed on January 10, 1994. Both parties submitted new versions of the draft agreement of December 27, 1993 and of the Security Annex (for the Israeli draft, see File A 5161/10, p. 51). However the effects of the crisis with Arafat at the end of December were still felt. On January 12, Oded Eran reported to Savir on an encouraging meeting with Arafat’s economic adviser, Maher el-Kurd (see Document 24). However, a report from Stanley Sheinbaum, who visited the PLO leader in Tunis on the same day, presented a bleaker picture. Sheinbaum sought to convince Arafat that his statements on issues that should be left for the permanent settlement negotiations and his demands for symbols of sovereignty were doing harm. Even Arafat’s supporters feared that the Palestinians would be left with nothing. Sheinbaum said that Arafat’s reaction did not indicate any change in his attitude. He explained that his aim was to protect the dignity of the Palestinian people and rejected the claim that his request to expand the Jericho area would include six Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory. Even if it did, he had no objection to the IDF securing the settlements. Sheinbaum felt he could not convince him that Rabin sincerely intended to reach a peace agreement. In view of complaints about the undemocratic way that Arafat ran the movement, Sheinbaum said that the path to strengthening his leadership was holding elections in the Territories (see: Document 25, Eytan Benzur to Eitan Haber, Report on Conversation with Arafat. See also the report by Washington-based researcher Judith Kiefer to Benzur on growing alienation between the PLO in Tunis and the leadership in the territories, complaints about Arafat’s conduct and demands for democratization, Document 28, Eytan Benzur to the Israel Embassy in Washington).

The first page of Sheinbaum’s report to Benzur, File 7705/6

Sheinbaum also warned about the US attempt to revive the Syrian peace channel at the expense of a settlement with the Palestinians. Indeed, as part of these efforts, a summit meeting was held between Presidents Clinton and Assad in Geneva on January 16. Dennis Ross and his team told Rabin that Assad had expressed willingness to normalize relations with Israel and negotiate a peace treaty with it, and had said he did not intend to intervene in the Palestinian talks. It was clear that the price of such an agreement would be complete withdrawal from the Golan, and large sections of the Israeli public were shaken by signs that Rabin was willing to hold a referendum on the issue. But it turned out that Rabin did not even have a majority in the Knesset to pass a referendum law, and the Americans and Syrians saw Rabin’s proposal as an exercise in evasion. On January 21, Assad’s eldest son was killed in a car accident, and US contacts with Syria were suspended.

The coolness between Peres and Arafat did not last long. On January 22, they met in Oslo at the funeral of Norwegian Foreign Minister Holst, after the stroke he suffered in December 1993 proved fatal. Before Peres left, Rabin spoke to him on the phone and expressed his concern that Israel was making too many concessions and that its position was being chipped away without the other side committing itself to the main points of the agreement. “We always give without getting their agreement to something we raised … .. We need to know if there is a deal or not,” he said. Peres promised to clarify this in his conversation with Arafat (see Document 26, telephone conversation between Rabin and Peres). In Oslo, Peres and Arafat decided on another round of talks to solve the problem of the border crossings. They would meet in Davos, Switzerland, during the World Economic Forum conference.

Based on the issues agreed in Oslo, Joel Singer and Abu Ala prepared a new draft agreement that left the points of dispute open. It said that Israel would be responsible for the security of the borders with Egypt and Jordan. Without reducing Israel’s overall responsibility for the Rafah crossings and the Allenby Bridge, the Palestinians would provide services in the Palestinian areas of the transit terminals. Arrangements were also made for preventing Palestinian entry without permission, for access to holy places in the Jericho area, for the security of Gush Katif, for the early exercise of Palestinian powers (early empowerment) in civilian areas and more. The draft was subject to Rabin’s approval (Document 27a. Draft of the Cairo Agreement, January 22, 1994). On his return from Oslo, Peres said in an interview on Israel radio that “this time Arafat was focused and to the point” (Document 29).

However, the draft agreement also revealed disagreements among the Israeli negotiators. Members of the defence establishment demanded a more cautious approach, and even Rabin’s adviser Jacques Neriah sent him a paper about the wording reached in Oslo, noting points that needed clarification. He claimed that alongside some Palestinian concessions, Israel had made some of its own in a careless way (Document 27).