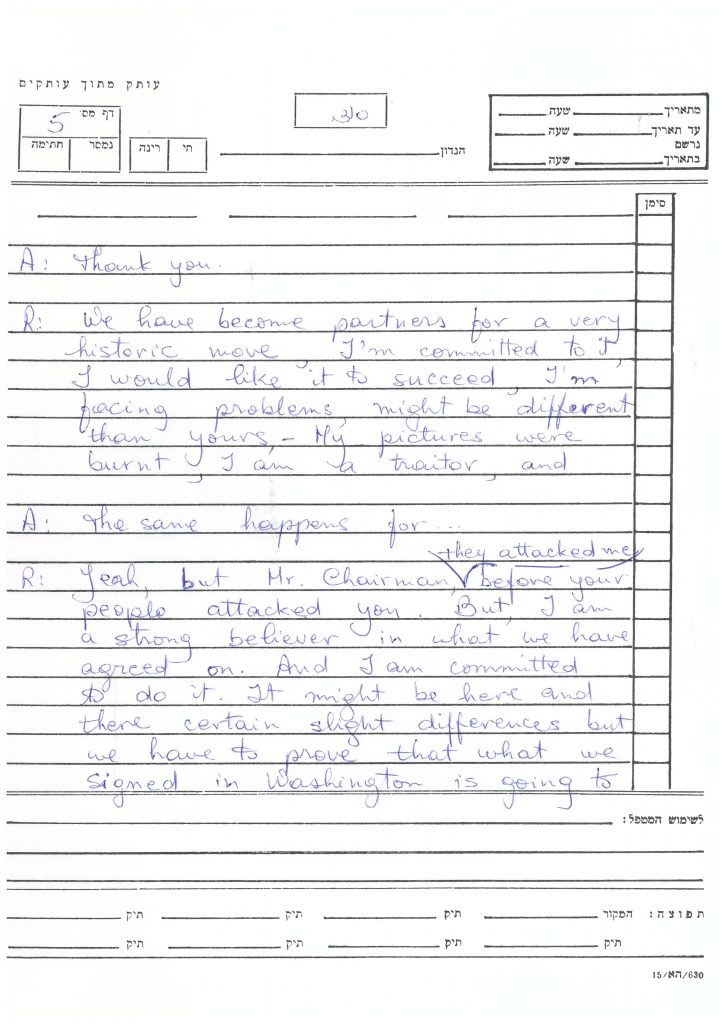

ד.1 | The attack on Muslim worshippers in Hebron: reaction in Israel and abroad

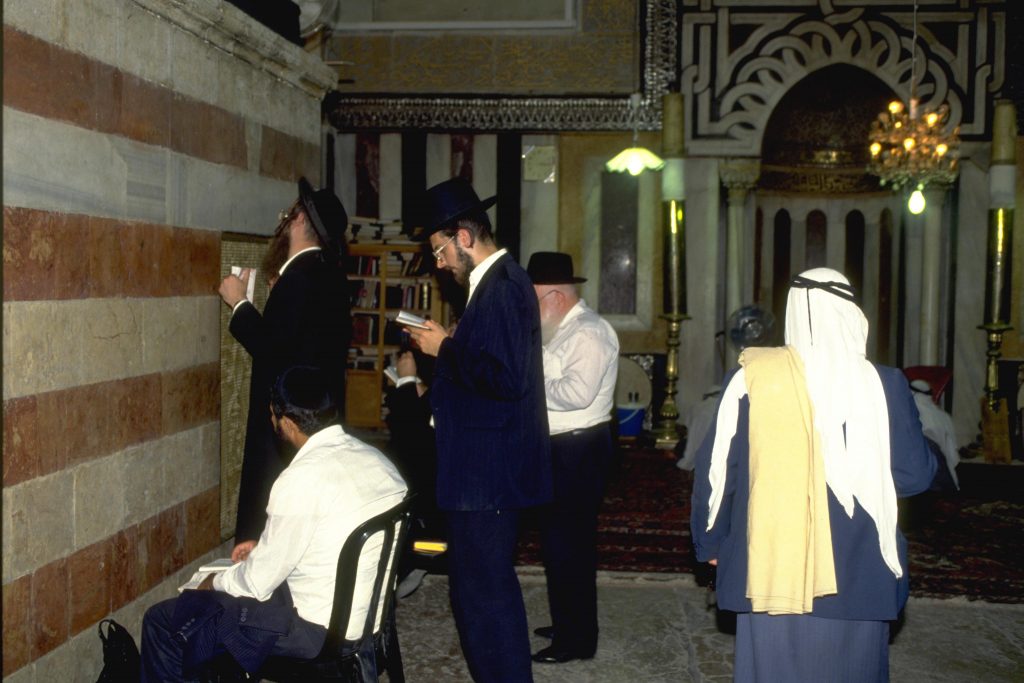

Jews and Muslims pray together in the Isaac Hall, Tomb of the Patriarchs, Hebron, August 1993. After the massacre the two groups were separated. Photograph: Moshe Milner, GPO

On Friday, February 25, 1994 (which was also the Jewish holiday of Purim) at 5:30 a.m., Baruch Goldstein, a physician from Kiryat Arba and an activist in the extremist Kach movement founded by Meir Kahane, entered the Hall of Yitzhak in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron and opened fire with a machine gun on the Muslim worshippers who were marking the month of Ramadan. He fired 108 shots until his gun jammed. While Goldstein was trying to change the cartridge, one of the worshippers attacked and disarmed him. He was then attacked by other worshippers and killed. A total of 29 people praying in the Cave were killed in the incident and 129 were injured. The news soon spread in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza and around the world. Serious riots broke out in the territories and in East Jerusalem, in which more people were killed and wounded by IDF soldiers. The media reported riots and demonstrations in the territories and inside Israel, and the reinforcment of the IDF and police forces in order to stop them.

Immediately after the news spread, Prime Minister and Defence Minister Rabin issued a strong condemnation: “A loathsome criminal act of murder was committed today in a site holy to both Jews and Arabs in Hebron. The prime minister and minister of defence, government ministers and the citizens of the State of Israel condemn in the most severe terms this terrible murder of innocent civilians”. Rabin asked Arabs and Jews alike to exercise restraint and not be drawn into violence that would worsen the situation, and promised to do everything possible to expedite the discussions in the peace process. Rabin also ordered the IDF and security forces to prevent further incidents of violence and bloodshed (Document 47, Prime Minister’s announcement, February 25, 1994). The government also issued a resolution condemning the massacre and promising to compensate the families of the victims (Document 48, Government Resolution), but despite efforts to prevent further friction, reports continued to flow in of casualties in local disturbances

The response of the Palestinians and the Arab world

The massacre united the entire Palestinian political spectrum in harsh condemnation. The fact that Goldstein was in uniform and that IDF soldiers who were guarding the Cave did not prevent the massacre led to a belief that there was a widespread conspiracy. Opponents of the Oslo agreement in the PLO, and even its supporters, claimed that the delay in the talks had encouraged the massacre and demanded an international presence to protect the residents of Hebron. They also demanded evacuation of the settlers. Nabil Shaath, who just two days earlier had ended talks in Cairo with Amnon Lipkin-Shahak, said the parties were very close to announcing the signing date of the agreement and a withdrawal timetable, “but we cannot sweep under the rug what happened in Hebron. Although I do not support at all breaking off these discussions. I think peace is of great value.”

Among the Palestinian opposition, the PFLP’s representative on the PLO executive committee, ‘Abd al-Rahim Maluach, called on Arafat to resign and to establish a temporary leadership. Some Fatah members in Tunis called on him to end the talks with Israel, to cancel the Oslo Accords and to return to negotiations based on a comprehensive solution and immediate Israeli withdrawal. A Hammas spokesmen in Jordan called for an emergency meeting of Arab states to end the talks with Israel and to intensify the Arab boycott.

Arafat himself was in a difficult situation. In interviews with the NBC and CNN stations, he said that the entire peace process had lost its credibility, that Rabin had delayed the process, and that the massacre was the result of a conspiracy involving the Israeli army. He announced the suspension of participation in talks in Washington, and called on the negotiators on behalf of the PLO in Egypt, Washington and Paris to return to Tunis for consultations. He accused the IDF of neglecting security in the holy places and called for an emergency Security Council meeting to condemn Israel and adopt his conditions for resuming talks:

- Disarming the settlers

- Dismantling the settlements in the Gaza Strip

- Stationing a temporary international force in the territories

- Restricting the movement of settlers in Kiryat Arba

- Increasing the number of Palestinian police officers.

However, Arafat agreed in principle to an invitation issued by US President Bill Clinton to transfer the talks to Washington (see below). He announced that the decision to return to talks would be made after his talks with the negotiators (Document 50, Clinton statement, February 25, 1994, see also File A- 7707/5).

According to a foreign ministry analysis, Arafat was under American pressure not to harm the process. In his own interest he knew that he must continue the negotiations and even speed them up, in order to make the agreement a reality. His remarks showed that he wanted a respite in order to calm things down and give him a political achievement, both as a means of weakening the opposition in his camp, which was challenging his leadership in an unprecedented way, and of exploiting the situation to achieve some of his demands from Israel and the United States. According to the report, Arafat enjoys support in his organization – Fatah – and other organizations. “They continue to support the process but demand more democracy.”

In the Arab world, there is often a gap between positions expressed in the media and the official positions of Arab countries. The media reacted with furious condemnation of the massacre, but the Arab states involved in the peace process such as Egypt, Jordan and even Syria, responded with relative moderation. Arab states that opposed negotiations with Israel used harsh language and demanded an end to the process (Document 60, Characteristics of Reactions to the Hebron Massacre, March 1, 1994).

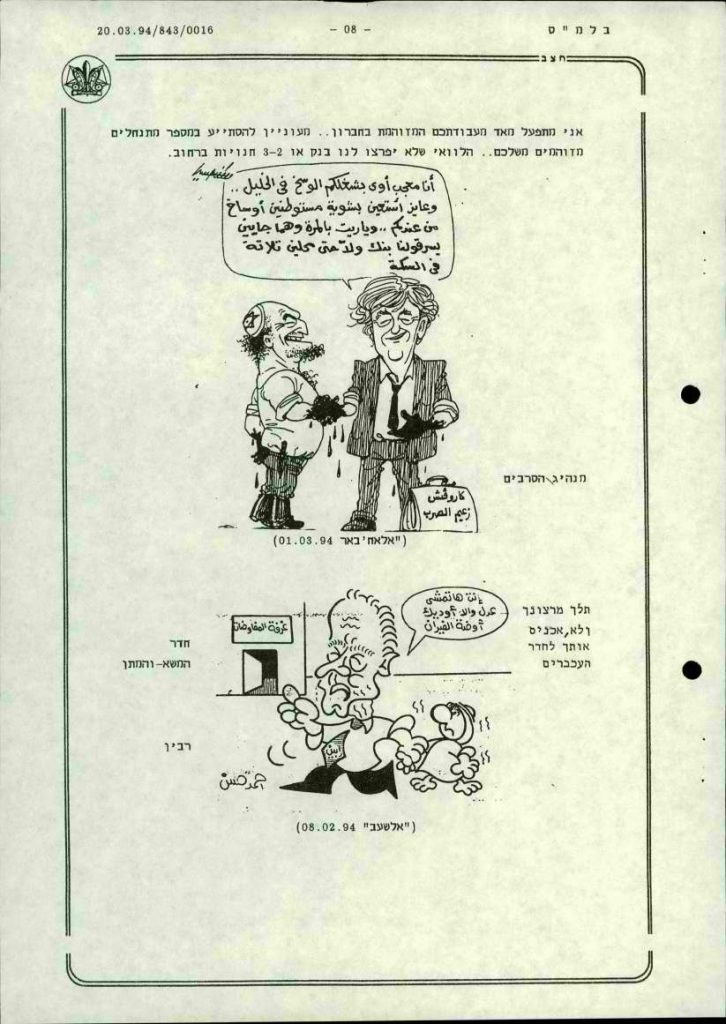

From a collection of cartoons from the Egyptian press about the massacre, File A 7707/7

For this chapter, see also Document 51, Foreign Ministry Report on the Responses of the Palestinians and the Arab World, 26.2.1994, Document 66, Center for Research and Planning to the Director General’s Office, 3.3.1994, Document 71, The Palestinian Camp Six Months after the Oslo Accord 8.3. 1994.

Israel’s response

PM Rabin’s briefing to the diplomatic corps in Israel, 26.2.1994. On his right, Danny Yatom, Central Command Commander, and Chief of Staff Ehud Barak, on his left, Deputy Foreign Minister Yossi Beilin. Photograph: Yaakov Saar, GPO

In a briefing to the foreign diplomatic corps on February 26, Rabin spoke about the attack and Goldstein’s personal background. He said that he had spoken to Arafat on the phone after the massacre and told him that there was no proof that that Goldstein had not acted alone. He was ashamed that a Jew and an Israeli had committed such an atrocity. Speaking the next day at a conference of the Jewish media, Rabin repeated that although Goldstein had acted alone, he was ashamed of those who publicly supported his action. Goldstein had not only killed innocent Palestinians while praying, but in doing so joined Hamas and Islamic Jihad with the aim of killing the peace negotiations. The prime minister expressed the hope that the PLO would choose to continue the process, as the Israeli government had decided to continue despite terrorist attacks by those opposed to the agreement. Rabin noted that he did not oppose President Clinton’s proposal to move the talks to Washington (Document 55, Rabin’s speech at the Jewish Media Conference).

In conclusion, the prime minister detailed the government decisions made that day to ensure the safety of the residents of the territories, which was Israel’s responsibility under international law (see Document 48 above). On February 27, the Israeli government decided to establish a state commission of inquiry to examine the events in the Cave of the Patriarchs and to take measures against extremists. The Attorney General was instructed to examine the possibility of outlawing the ‘Kach’ and ‘Kahana Chai’ organizations. (Document 56, Government Decision, 27.2.1994).

The commission of inquiry was headed by Supreme Court President Meir Shamgar and its members were Supreme Court Justice Eliezer Goldberg, Nazareth District Court Vice President Abdel Rahman Zoabi, Open University President Menachem Yaari and former Chief of Staff Maj. Gen. Moshe Levy. Its findings were presented to the prime minister and police minister on June 28. The government decided to adopt the report (see evidence before the committee, the main points of the report and the government’s decision in File A-7707/7).

The massacre in Hebron provoked a violent reaction in the Israeli public. Many heads of organizations and private citizens wrote to the prime minister, the president and the foreign minister. Many strongly condemned the massacre but some expressed concern that the government and the media were tarring all settlers with the same brush. Some challenged the possibility of a lasting peace agreement with the Palestinians, arguing that the situation was not yet ripe for an agreement between the peoples. There were strikes and demonstrations by the Arab public throughout the country, including violent outbursts. Arab representatives demanded that the prime minister outlaw the extremist movements and suppress them. (See Files GL-23306/6 and MFA-8559/6).

On February 28, a debate was held in the Knesset plenum on the massacre in Hebron. After condemning the massacre, Rabin said the Palestinians should strive to rise above it and to continue the peace process. He believed that the discussions would resume within a few days (Document 58, Prime Minister’s announcement, February 28, 1994). At the end of the debate, a summary was adopted by a majority of 93 Knesset members with one objection. It said that the Knesset expressed shock at the murder and shared the mourning of the families. It condemned the expressions of sympathy and understanding shown by individuals and extremists towards the massacre, but opposed any sweeping accusations against the settlers.

On March 13, the government decided to outlaw the Kach and Kahana Lives movements.

President Ezer Weizmann offers his condolences to the mayor of Hebron, 27.2.1994. Photograph: Avi Ohayon, GPO

Reaction in the United States and around the world

Following the massacre, the United States stepped up its involvement in the Israeli-Palestinian channel alongside its efforts to advance talks with Syria. At a White House news conference on February 25, President Clinton called on the parties to return quickly to the negotiating table and suggested that the negotiating teams be sent to Washington to conclude the negotiations. He claimed that it was no coincidence that the killer chose the month of Ramadan and a site sacred to Muslims and Jews alike. (Document 50, Clinton statement, February 25, 1994). A foreign ministry telegram quotes “knowledgeable American sources” who said that until now the Administration had acted as an observer at the negotiations, but if they were moved to Washington, the Americans would take a more active role. State Department experts would play a role and, if necessary, take part in the talks themselves, but would not impose solutions or conditions on either party. As for the UN, Secretary-General Boutros Ghali wrote to Rabin, suggesting that despite Israel’s well-known opposition to the deployment of military observers in the territories, some UN presence should be considered in light of the circumstances, in cooperation with the Israeli government. (Document 52).

(See also Documents 54, 61. Additional responses from around the world are in File A-7707/6).

A message from French Foreign Minister Alain Juppe to Peres condemning the massacre, File MFA 8570/1