א.1 | Syria refuses to give a list of Israeli prisoners

At the end of October 1973, for the first time since 1948, Israel had hundreds of missing soldiers, some of whom were prisoners. This fact, and the images of the prisoners shown on Arab television channels, led to a severe public reaction and added to the loss of trust in the establishment as a result of the war. The Syrians, and initially the Egyptians too, refused to observe the Geneva Convention of 1949, which established the rights of POWS. They used the prisoners for political purposes as a bargaining chip. It was known that some of them had been murdered, and Israel filed a complaint with the UN and the International Red Cross, which is responsible for the treatment of POWS according to the Geneva Convention (See File G 6695/3).

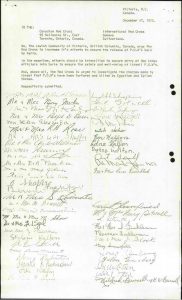

Looking through photographs of the POWs, ISA press photograph collection, TS 3009/513

Unlike Syria, Israel considered the return of prisoners, determining the fate of the missing and returning the bodies of the fallen as sacred principles, and acted in accordance with the Geneva Convention regarding the prisoners in its hands. It handed over lists of names and allowed visits by representatives of the Red Cross. As early as October 22, the government decided that it would not agree to a ceasefire without an exchange of prisoners.

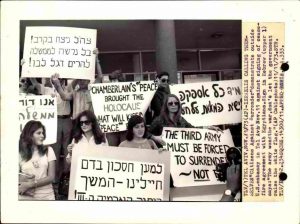

During the fighting, a blackout was imposed on the number of prisoners and missing soldiers by the military censorship. After the ceasefire, the foreign minister, Abba Eban, announced that Egypt had provided information about the POWs in its hands. However Syria refused to give the Red Cross a list of the POWS. According to press reports, on October 25 a Syrian officer unofficially informed a Lebanese newspaper that it held fifty prisoners from the Hermon outpost that fell at the beginning of the war. On the same day, a group of mothers and wives of the POWs was formed and submitted a petition calling on the government to promote an exchange of prisoners within 24 hours. The turmoil and dissatisfaction among the family members worsened after they heard that Israel had agreed, under pressure from the US, to transfer supplies to the encircled Egyptian Third Army. Another letter of protest was sent and a debate was held in the Knesset at the request of the Likud. Opposition leader Menachem Begin demanded that the Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat, intervene with the Syrians for the release of the Israeli prisoners. He also referred to US promises made when Israel agreed to the ceasefire, to get a commitment from the Soviet Union regarding the prisoners.

Demonstration against supplying the Third Army, 11 November 1973. ISA press photograph collection, TS 3010/219.

On October 29, the Egyptians handed over a list of wounded prisoners at a meeting held at Kilometre 101 on the Suez-Cairo road. After the signing of the “Six Point Agreement” between the parties, the POWS in Egypt were returned to Israel during November 1973. The families of the missing on the Syrian front then became the main pressure group. Their activities had a great impact on the government ministers, and especially on Prime Minister Golda Meir. After the war her sensitivity to criticism increased, she felt that she was not receiving support from the party, and contacts with the prisoners’ families added to her anxieties.

According to the information Israel had, there were about 131 MIAs on the Syrian front, who were considered prisoners. Rumours that many of them were murdered by the Syrians continued to spread, and a report based on Red Cross sources was published in the press that 100 prisoners were murdered. Although the Red Cross denied it, Israel announced that it would not open negotiations with Syria before it handed over the list.

The enclave or salient held by Israel inside Syria. Wikimedia Commons

At the end of the war, the IDF had captured an enclave inside Syria and was within cannon range of the outskirts of Damascus. As early as November 1973, Israel linked the prisoner issue to a proposal to withdraw from territory captured during the war. In response to Israel’s claims to the UN that Syria was not acting according to the Geneva Convention, Syria submitted complaints to the Security Council about Israel’s treatment of civilians in the territories it occupied and the expulsion of the villagers, which were also contrary to the convention. In November 1973, Israel informed the Syrians, through the US and the Red Cross, that it was ready to allow 15,000 villagers who left their homes during the war to return to the territory under its control. It even offered to turn over to the UN the Syrian outposts captured on Mt. Hermon in 1973, in exchange for the return of the prisoners (Document 1, A 7075/1, p. 74). This concession made difficulties for the government later during the discussions on the separation of forces. In response, the Syrians demanded the evacuation of all the territories occupied in 1973 and the recognition of PLO members as combatants. Israel did not respond to these demands.

The Foreign Ministry, which was responsible for contacts with the Red Cross, realized that the POWs were being used as hostages. Their representative, Mordechai Kidron, wrote to the ministry’s Director-General that the Syrians clearly understood the value of the card in their hands. They were not interested in the Geneva Convention and the problem would only be resolved within the framework of a political/territorial deal – that is, including Israeli withdrawal. The representative of the Red Cross in Israel, Michel Convers, also thought that the POW problem could only be solved as part of a “large package” deal (Document 2, MFA 6807/5).