א.1 | World Jewry "discovers" the Jews of Ethiopia

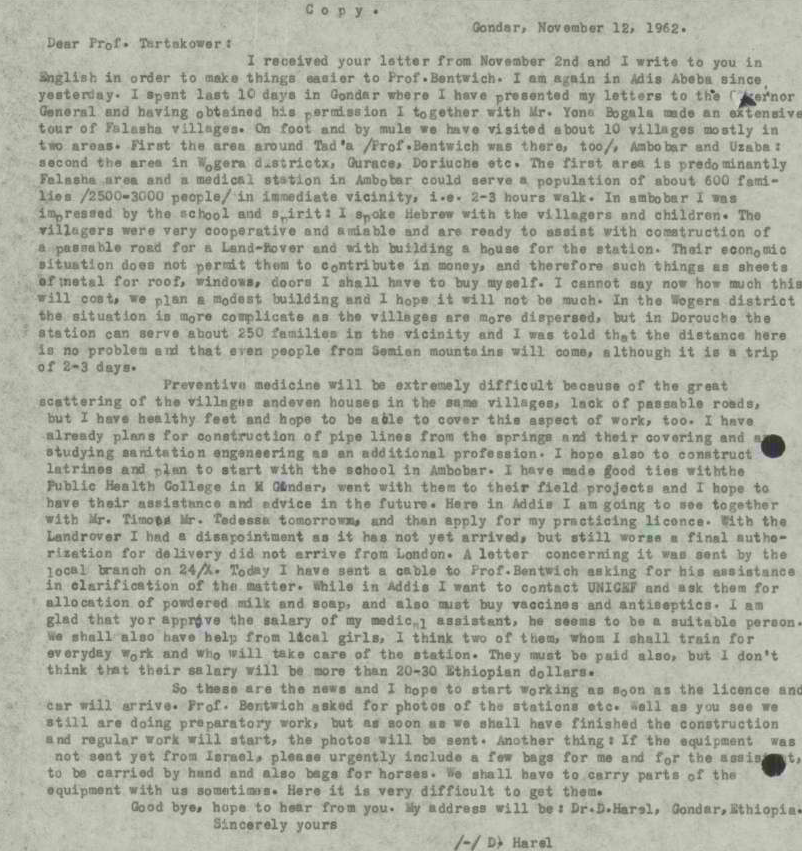

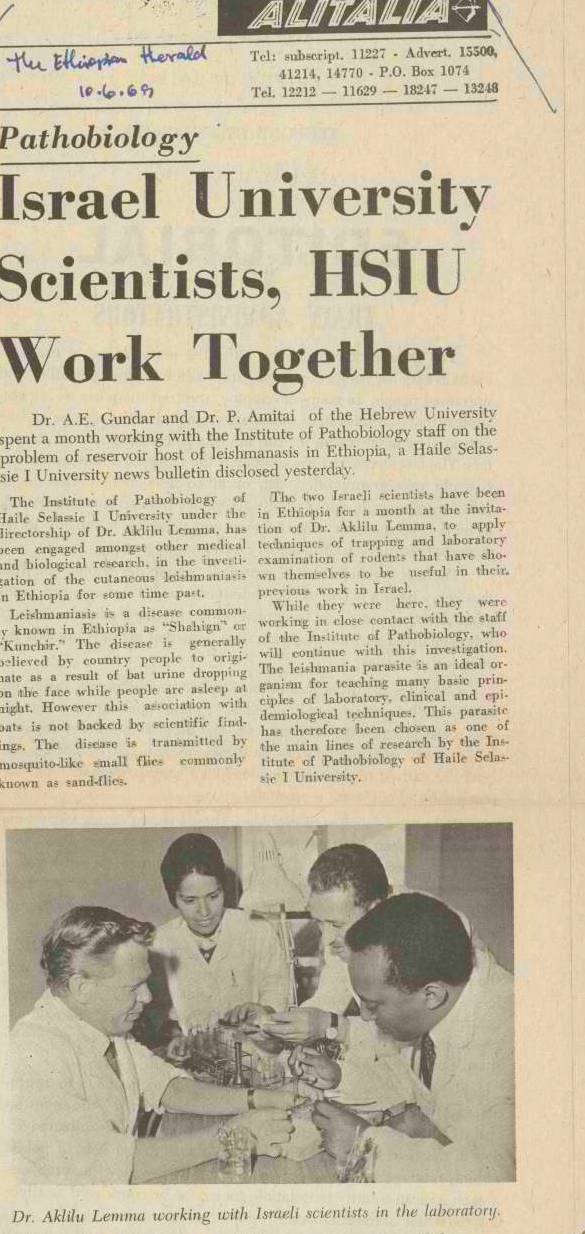

Since the 9th century, fragments of information about Jews living in Ethiopia reached Jewish communities around the world, but no real contact was made with them. The community was almost entirely isolated from the Jewish world. However, since the end of the 18th century and especially in the 19th century, during the colonial period, interest in the Beta Israel community (their preferred name) increased. At the time they were known as “Falashas”, a derogatory term still found in many of the early archival files. In the 1860s, European Jews began to call for the spiritual-religious salvation of the Ethiopian Jews, many of whom had converted to Christianity. The first emissary from the Alliance Israélite Universelle, Joseph Halévy, visited the villages of the “Falashas” in 1867. Ties were strengthened at the beginning of the 20th century, when Halevy’s student, Dr. Jaques Faitlovitch, worked to deepen the connection between Ethiopian Jews and the Jewish people and to introduce them to mainstream rabbinic Jewish law. He established a Jewish school in Addis Ababa, and other emissaries came to Ethiopia over the years and maintained contact with the community.

(See more on Faitlovitch’s work in President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi’s files on the Ethiopian Jews – PRES-10/9, PRES-10/10, PRES-10/11)

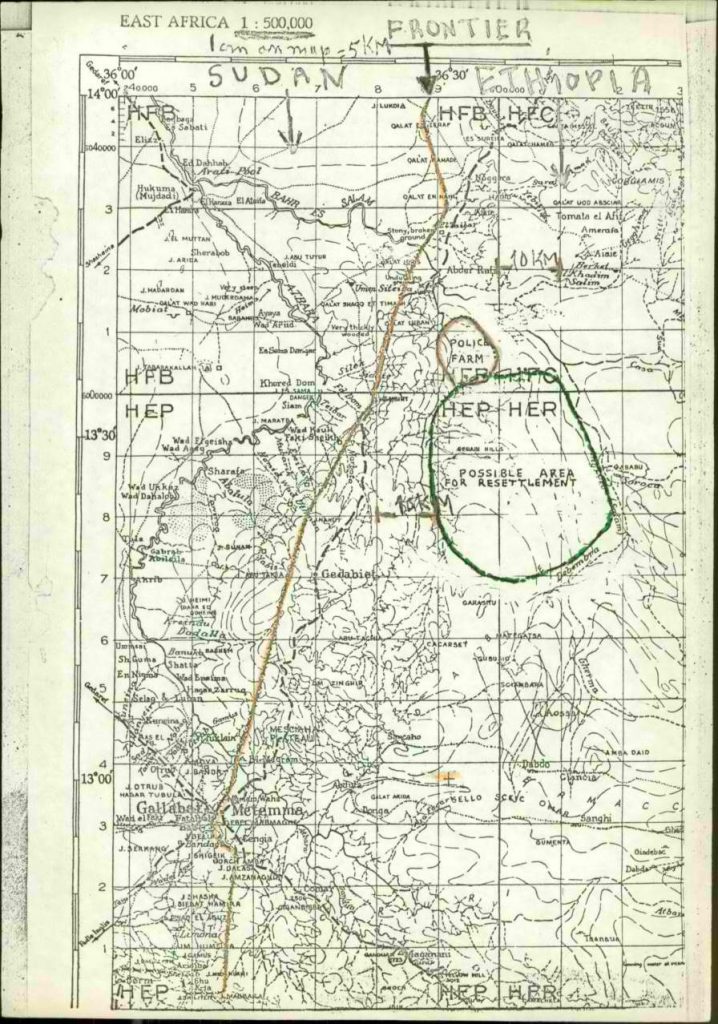

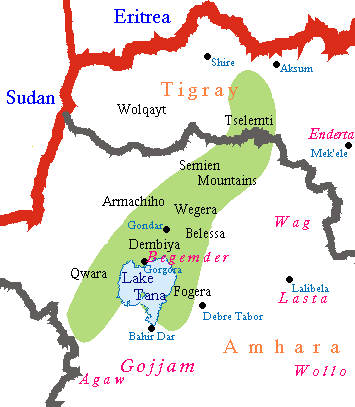

The area of Jewish settlement in Ethiopia, Wikipedia