א.1 | 1. Exploring the possibilities for an agreement with Jordan, September 1993 - April 1994

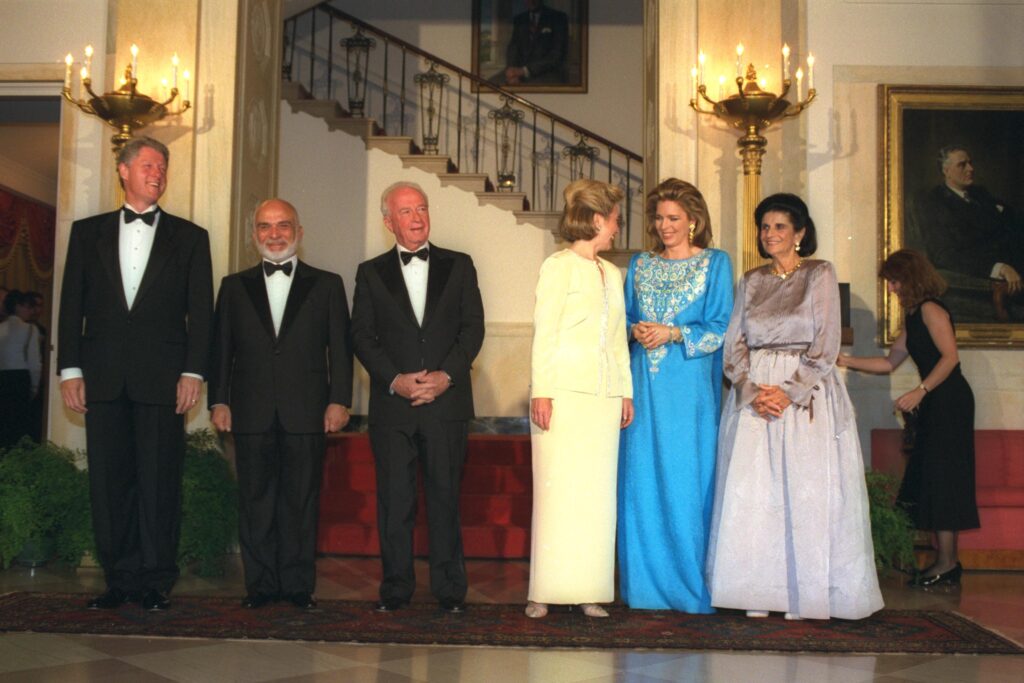

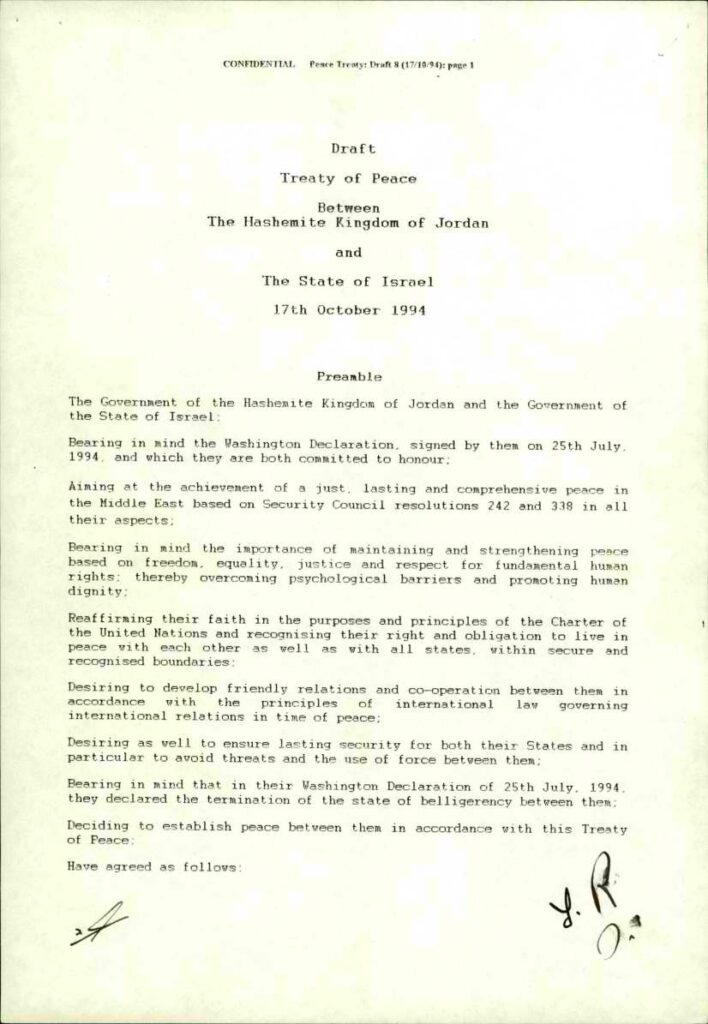

On October 26, 1994, the representatives of Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in a solemn ceremony near the Arava border crossing, north of Eilat, later known as the Yitzhak Rabin crossing. The ceremony was the culmination of a process that began with the two countries’ decision to move towards a new era in their relations – from rivalry to partnership and from hostility to peace. The agreement was very important to Israel: it ensured peace on the eastern border, its longest border, weakened the effect of the Arab boycott, and, above all, strengthened the security partnership with Jordan and made it visible. The partnership with Israel was also very important to Jordan, especially in the economic, political and security fields.

Israeli and Jordanian army officers shake hands during the ceremony of signing the peace treaty, 26 October 1994. Photograph: Avi Ohayon, GPO

The signing ceremony was a historic moment. The citizens of Israel and Jordan who were invited to it, some of them veteran soldiers who had fought for years on opposite sides, and guests from all over the world, witnessed the agreement of the two countries to live side by side in peace. They saw the prime minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin, commander of the Harel Brigade in the War of Independence and chief of staff in the Six Day War, standing by the side of King Hussein ben Talal, the head of the Jordanian kingdom. Rabin and Hussein had known each other for many years, and Israel-Jordan relations had also begun much earlier, But every time an attempt was made to reach a formal agreement between them, another obstacle blocked the way. An example of these past contacts can be found in the appendix, which presents a secret meeting between Rabin and King Hussein and other leaders in 1975.

In this publication we present a collection of documents from recently declassified files, showing the difficulties that arose on the way to the agreement and how they were overcome. We also present many of the documents on a timeline, which illustrates the chain of events that led to the ceremony in the Arava. The starting point we have chosen is September 13, 1993. On that day, in Washington, Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen) of the PLO – in the presence of Prime Minister Rabin and Yasser Arafat – signed a Declaration of Principles (DOP) on interim arrangements for Palestinian self-government, known as the first Oslo Accord. (See the publication of the Israel State Archives on “The road to Oslo“). The signing of the DOP removed an important obstacle on the way to the peace process with Jordan, and on the very next day, September 14, an agreed agenda was signed in Washington between the two countries for the continuation of the process (Document 1).

The timeline reflects the affinity between the two peace processes – the Jordanian and the Palestinian, which ran concurrently and influenced each other. The fact that the majority of Jordan’s population is Palestinian, and that there were economic and family ties between Jordan and the West Bank, ruled by Jordan until 1967, created a sense of obligation on the part of the Jordanians towards the Palestinians. The influence of the Palestinian issue on Israel-Jordan relations was also reflected in the Madrid Peace Conference at the end of October 1991, which brought together representatives of Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt and a joint Jordanian-Palestinian delegation and marked the first official contacts between Israel and the Palestinians. Following the conference, talks were held in Washington between the Jordanian-Palestinian delegation and the Israeli delegation, headed by Government Secretary Elyakim Rubinstein and Abd al-Salam al-Majali, who was appointed prime minister of Jordan in May 1993. Many of the issues that would arise later in the negotiations were already discussed in Washington, and in fact the Agenda had already been agreed and initialled, but was not published. The Washington talks did not mature due to the opposition of the PLO, which wanted to control the Palestinian negotiations. With the signing of the Oslo Accord, the Jordanians were freed from their commitment to the Palestinians, and could focus on their own interests.

Elyakim Rubinstein (centre) and members of the Israeli delegation in Washington, October 1992. Seated on the right, the Jordanian delegate and water expert, Munther Hadadin. Photograph courtesy of Arie Zohar

But despite the lifting of the Palestinian veto, little progress was made in the first few months. At the end of September Rabin paid a secret visit to King Hussein in Aqaba, to explain why Israel had chosen to reach the Oslo Agreement, which had surprised and angered the Jordanians. He assured the king that Israel sought a speedy agreement with Jordan. This was followed by a secret meeting between Peres and King Hussein and his brother, Crown Prince Hassan, on November 2-3, 1993. At the meeting, the parties agreed on a non-binding document (Non-paper) initialled by Peres and Hussein, which was designed to ensure rapid progress towards a peace agreement, with an emphasis on economic cooperation. The following day the existence of the meeting was revealed in the Israeli media. This embarrassed Hussein on the eve of elections to the Jordanian Parliament, and he disowned the agreement (Document 2).

At the same time, trilateral talks between Israel, Jordan and the United States opened on November 4, with the aim of advancing the negotiations. More about these conversations, which dealt with economic issues, can be seen in Files A-8081/17, A-8083/15. Rubinstein also continued the bilateral talks with Fayez Tarawneh, the Jordanian ambassador to Washington, who had replaced al-Majali. However the teams encountered various difficulties. The leak about the Peres-Hussein meeting not only embarrassed Hussein, but also damaged Israel’s credibility. On February 25, 1994, the massacre of Muslim worshippers in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron took place, which shocked the Arab world, temporarily halted talks with the Palestinians and posed another difficulty in the talks with the Jordanians (See the chapter on the massacre and its results in the ISA publication on the Cairo Agreement). After the massacre, and in response to it, the Hamas Islamic terrorist organization carried out two major suicide attacks in Afula and Hadera. Israel, for its part, accused Jordan of giving shelter to Hamas operatives (ibid., Document 96).

Another difficulty arose due to the American naval blockade of the port of Aqaba, Jordan’s only outlet to the sea. The blockade was imposed following Jordan’s support for Iraq in the Gulf War (1991) and the suspicion that the port was being used by Iraq to circumvent the sanctions against it. In light of the economic damage, the Jordanians began to condition the continuation of the talks with Israel on the lifting of the blockade (Document 3).

In order to break the stalemate, the Israeli team made efforts to keep contacts alive and examined different approaches. The Jordanian side, for its part, was still reserved in its attitude to a full peace agreement, and preferred to discuss specific problems between the two countries, mainly the questions of water distribution and determining the border. Arie Zohar, the Deputy Government Secretary, warned that discussing each issue separately would prevent the parties from reaching mutual concessions. He recommended a “package deal” based on consideration of the issues important to each side (Document 4).

Despite the efforts of the teams, the only issue where real progress was made was in dealing with the problem of flies. The residents of the Jordan Valley and the Arava suffered from large amounts of flies, due to the overuse of fertilizers by farmers on both sides of the border, and both sides had an interest in addressing the problem. Its extent can be learned from the multitude of documents on this subject (for example in Files GL-66302/11, GL-66302/18).