ב.1 | From president to politician: Yitzhak Navon resumes his political career

Yitzhak Navon was the first and so far the only Israeli president to return to political life. As president, Navon was seen as a “man of the people” who listened to the needs of the disadvantaged. He tried to advance relations with Israel’s Arab citizens and its Arab neighbours, especially Egypt. He was very popular, especially when Menachem Begin, the prime minister, was retreating from public life. There were even suggestions that he would run against Begin. In 1983 Navon decided not to seek a second term, but in the end Begin retired in favour of Yitzhak Shamir. In the 1984 elections Navon, who had served as a Labour MK before he became president, returned to the Knesset. He had hoped to serve as foreign minister, but since the Labour party was forced to set up a National Unity government, it had to give the foreign ministry to Shamir. Navon became minister of education.

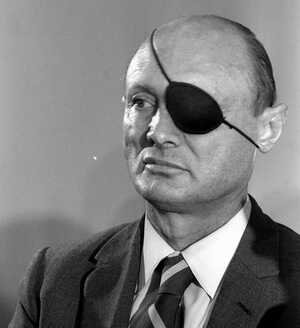

Incoming minister Yitzhak Navon with outgoing minister Zebulon Hammer, 16 September 1984. Standing at left the director-general, Eliezer Shmueli. Photograph: Chanaia Herman, GPO

The ISA has digitized a large collection of files on Navon’s term as education minister on our Hebrew website. Not all the files from the ministry are about Navon himself, but they give an overview of the issues he had to deal with. The Archives has also published more than forty short online publications in Hebrew on his activities as minister of education, culture and sport. Here we present highlights from these publications, showing his ambitious aims and the difficulties he had to deal with in the context of the National Unity government with the Likud.

Expectations from Navon were high. An Arabic teacher by profession, he had led an adult literacy program in the 1960s. He was also one of Israel’s few Mizrachi politicians, coming from an old-established Sephardi family on his father’s side and a Moroccan one on his mother’s. Yet a short time after he entered the Education Ministry, the press and the public were expressing disappointment with his performance.

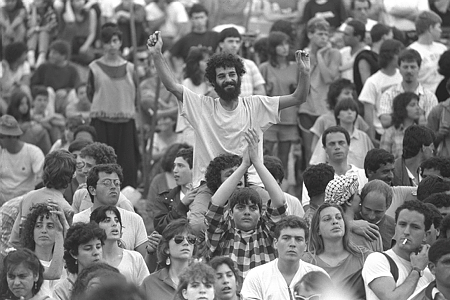

According to his memoirs, Navon had four main aims in the ministry: to educate students in values such as truth, honesty and respect for others and in their national and cultural heritage; to encourage education in democracy and co-existence between different groups – Jews and Arabs, Ashkenazim and Sefardim, religious and non-religious people; to encourage science and technology and to improve the students’ command of the Hebrew language. During the first two years of his tenure, Navon could do little to carry out these aims due to the budget cuts imposed by the Finance Ministry in order to deal with hyperinflation of 400% and the budget deficit. He was forced to fire 1,800 teachers and to cut hours, at a time when thousands of children were arriving from Ethiopia in “Operation Moses. He had to deal with labour disputes and student strikes over increases in university tuition fees.

Yitzhak Navon visits Ethiopian children learning Hebrew at the Talpiot school in Hadera, January 1985. Photograph: Nati Harnik, GPO

His presidential image as a person who stood above party and sought compromise rather than conflict made it difficult for him to stand up to pressure. Only ten months after his appointment, the “Yediot Ahronot ” newspaper wrote that he was indecisive and weak and gave him a grade of “almost good” (equivalent to a C pass). An even more fierce attack appeared in his own party newspaper, “Davar’, claiming that he was preoccupied with trivia at a time when the educational system was in crisis. His self-effacing style was described as “silence wrapped in chocolate”, and he was accused of pandering to the religious parties. Even when the economic situation improved, he found it hard to shake off his negative public image. By the 1988 elections he had become an electoral liability instead of an asset to the party.

This was Navon’s first ministerial post and he found it difficult to make an impact on the large and unwieldy bureaucracy. At first he had the help of Director-General Eliezer Shmueli. Shmueli came from the same kind of family and political background as Navon, who had even taught him Arabic. However in 1986 Shmueli resigned and was replaced by Dr. Shimshon Shoshani, an expert in educational administration and a dynamic personality. As head of the education department in Tel Aviv he had favoured new ideas about parental and school autonomy, which were criticized for widening social gaps.