Herbert Samuel and the British Mandate for Palestine: The Formative Years

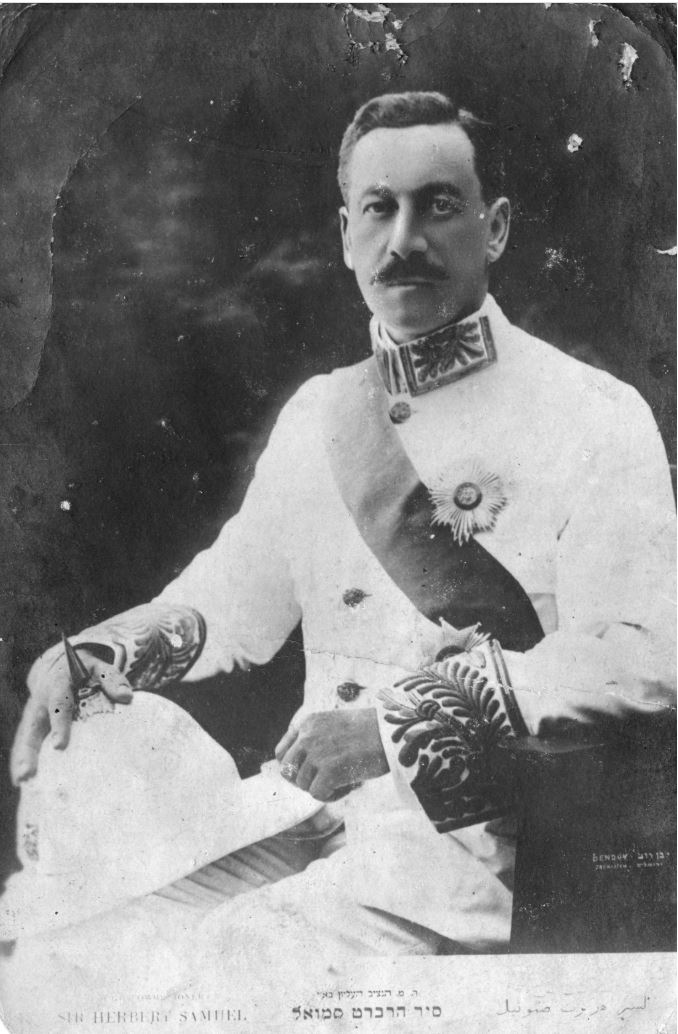

On June 30, 1920, Herbert Samuel, the first High Commissioner for Palestine, arrived in Jaffa and made his way to Jerusalem, thus beginning the British Mandate period. For most of us, this phrase is associated with a chapter in the history books, focusing on the British government's policy on political matters such as Jewish-Arab relations, immigration and security. The acts of the Mandate government in the civic sphere have been pushed to the margins of history. So who built the bridges, police stations and government buildings that stud our landscape, and much of the pre-state infrastructure, and why? Exactly 100 years after Samuel's arrival, we present an exhibition that addresses this question. It is based on a rich collection of documents, photographs and other materials left behind by the Mandate administration, Herbert Samuel himself and his son Edwin, and other people who lived through these years. With their help, we seek to present an outline of the formative years of the Mandate and to raise the question what remains of its legacy in Israel today.Herbert Samuel and the British Mandate for Palestine: The Formative Years

About the exhibitionHerbert Samuel and the British Mandate for Palestine: The Formative Years

Timeline

December 1917 General Allenby enters Jerusalem

October 1918 British forces capture the rest of Palestine, military government set up

April 1920 The Nebi Mussa riots in Jerusalem

25 April 1920 The San Remo conference awards the mandate to Britain

1 July 1920 Sir Herbert Samuel sets up a civilian government

May 1921 Anti-Jewish riots in Jaffa

July 1922 Ratification of the Mandate by the League of Nations

July 1925 Samuel is replaced by Lord Plumer

1928 Plumer leaves, replaced by Sir John Chancellor

August 1929 Anti-Jewish riots, mainly in Jerusalem, Hebron and Safed

1933 Rise of Adolph Hitler in Germany.

1936 The Arab revolt against British rule

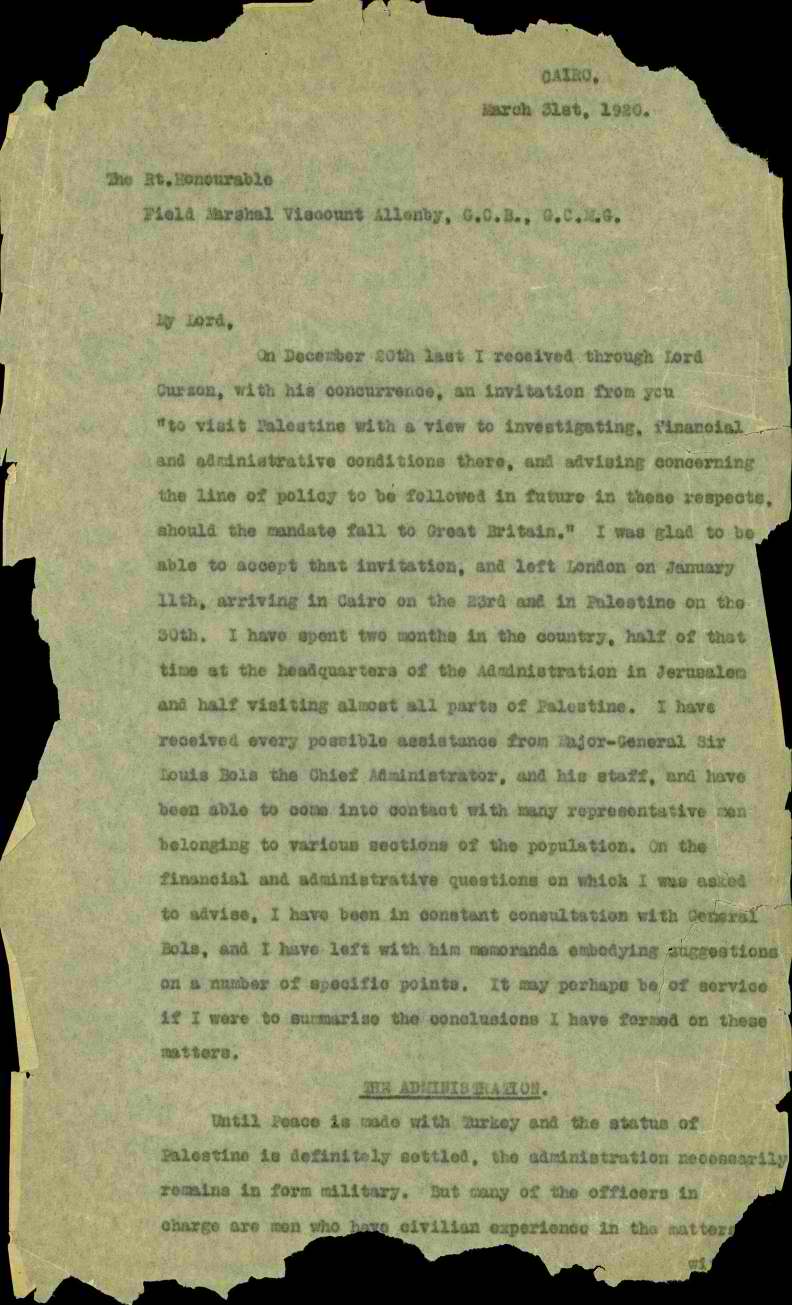

Samuel's letter to Allenby

When Samuel arrived in Jaffa in June 1920, this was not his first visit to Palestine. Samuel was a Jewish ex-minister in the government who supported the Zionists. In December 1919, Field-Marshal Allenby, the British commander in the area, asked him to visit Palestine and to investigate the situation in preparation for the grant of the the Mandate. Arriving in January 1920, Samuel spent a month at the headquarters of Major-General Louis Bols and toured the country. At the end of March, he wrote to Allenby with his recommendations, including appointment of an official in charge of education and changes in the legal system.

A development plan

Samuel listed areas requiring urgent development work:

Road construction

Communications: postal service and telegraph

Railways

Establishing a port in Haifa

Developing industry which barely exists

Agriculture and forestry

Establishment of a hydroelectric power plant

Sameul argued that development would allow Palestine to support a much larger population. In his view, “economically, the Zionist policy is quite practicible. Politically, too, if too much is not attempted at once, the difficulties…..are by no means insuperable.”

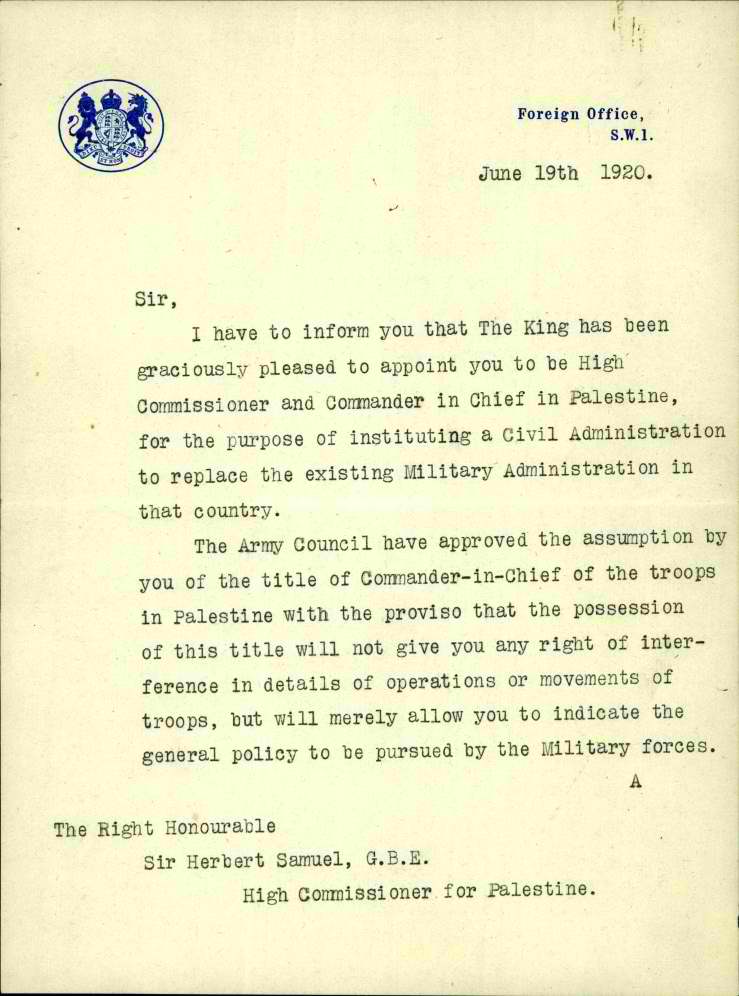

Letter from the Foreign Minister announcing Samuel's appointment by King George V, File 649/6

Item Link

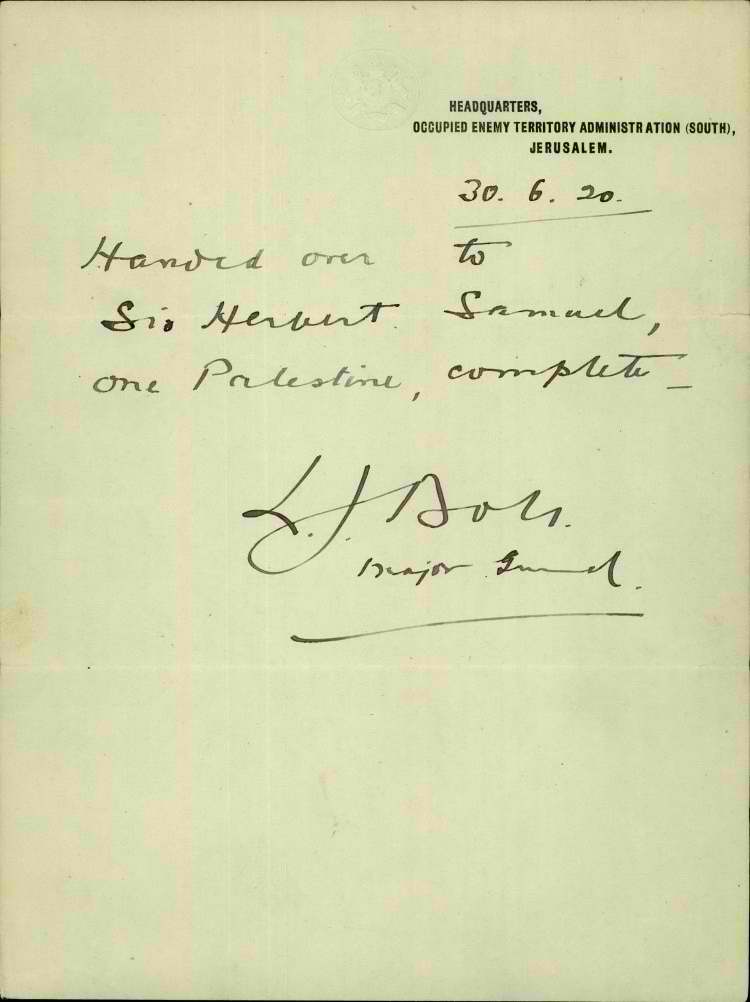

The receipt prepared for Samuel by the head of the Military Administration, General Bols. File P 649/6

Item LinkBeginnings

On taking office Samuel held receptions in Jerusalem and Haifa and made official visits to various places. He then set to work to carry out his plans. Government officials began drafting a series of ordinances designed to regulate many areas of life in Palestine. He set up an Advisory Council of senior officials and representatives of the Jewish and Arab public to hear their views on these laws. In the coming sections you can see some of the activities of the High Commissioner and his successors in these areas.

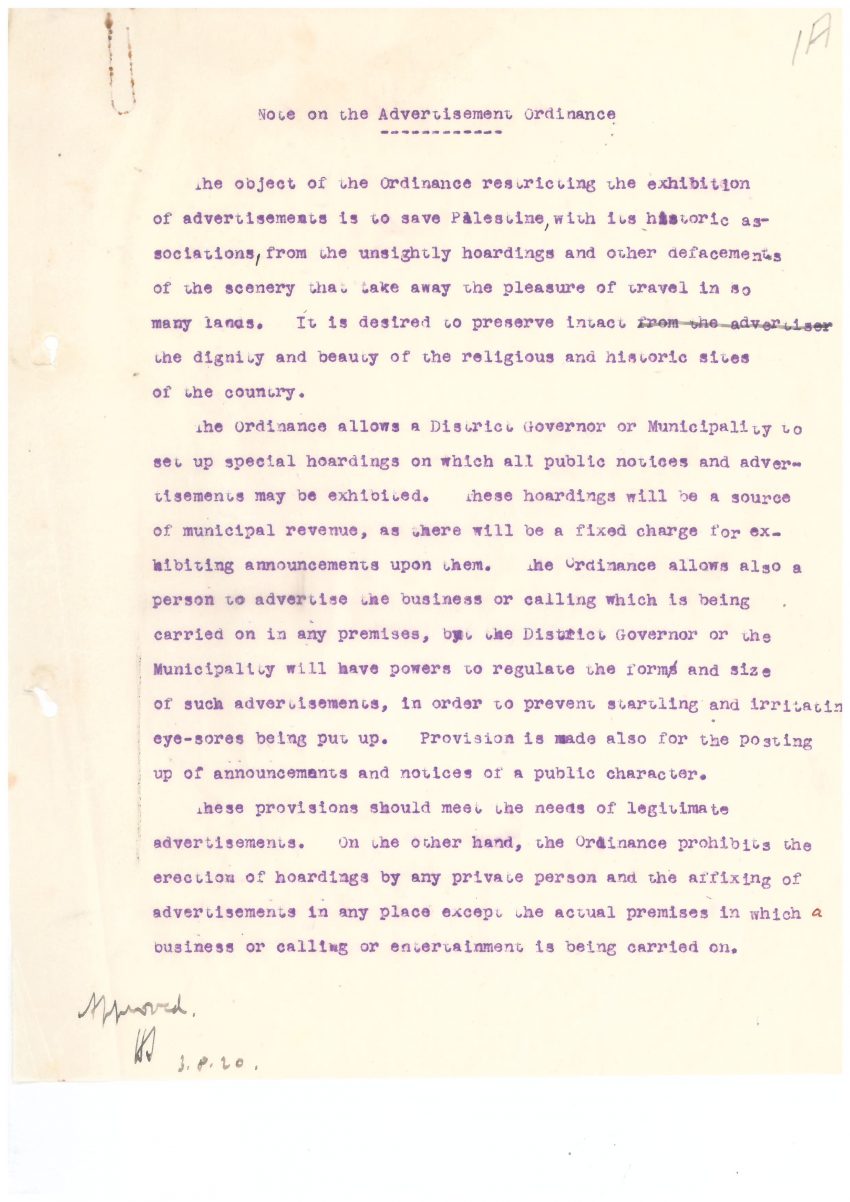

Explanatory note on the Advertisement Ordinance issued by Samuel on his arrival, File M 2/10

Item LinkEducation - the key to progress or a source of division and unrest

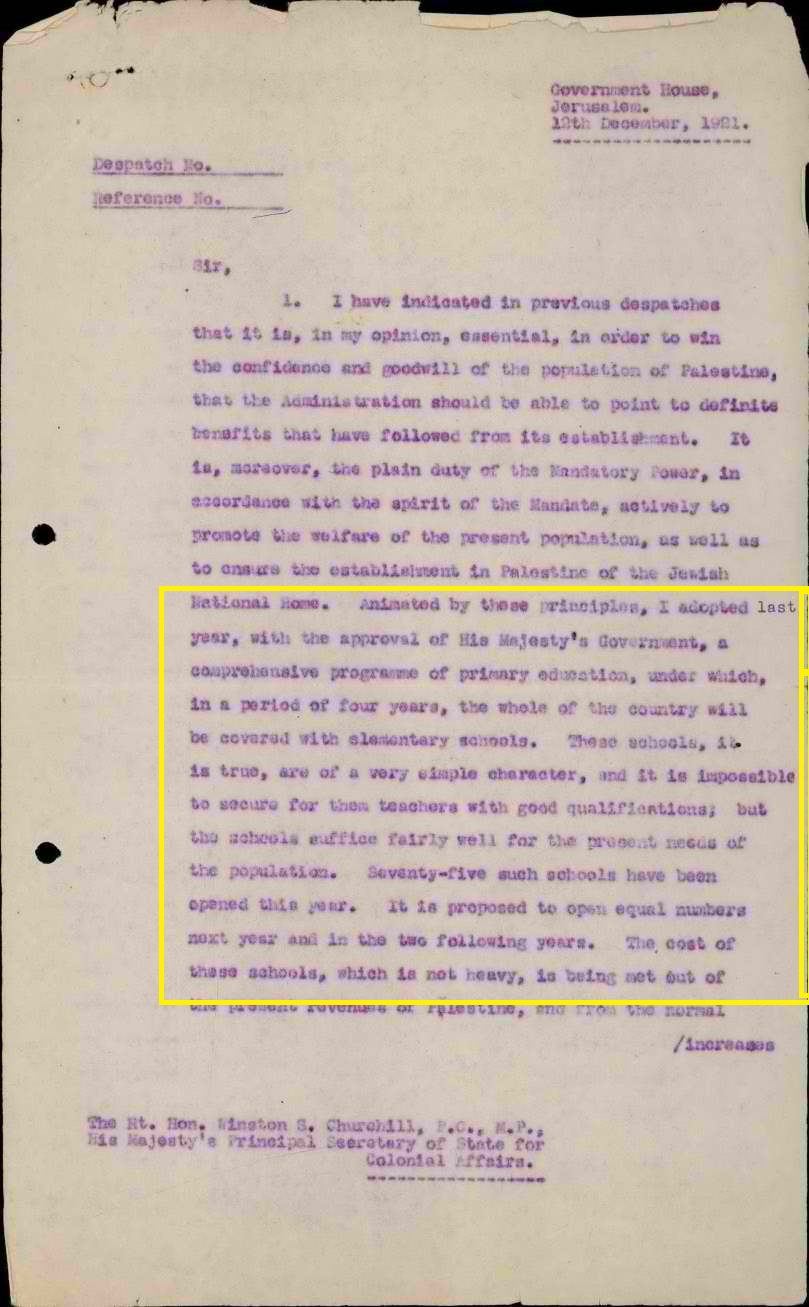

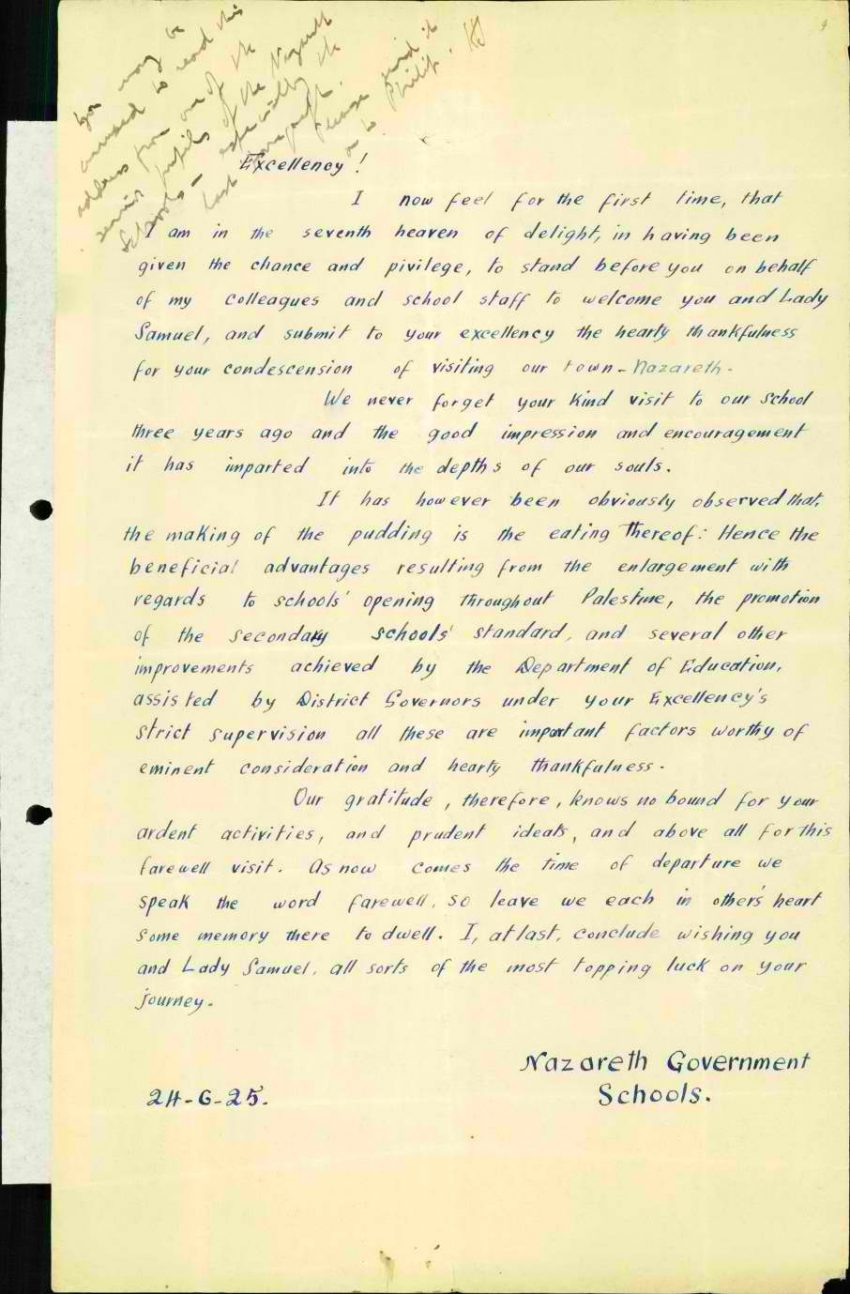

By the end of the Ottoman era, about 8,000 pupils attended government schools in cities alongside church institutions and traditional Muslim and Jewish schools. The more liberal High Commissioners believed in expanding education: Samuel tried to set up 300 village schools in four years, promising to pay the teacher’s salary if the village provided a building, but a financial crisis intervened. His successor, Lord Plumer, wanted to introduce universal education but the Colonial Office objected. Education made up only 5-7% of the budget and its aim was basic literacy. The Peel Commission (1936) was shocked to find that only 293 villages had schools and many children (especially girls) were rejected for lack of space.

First page of a letter to the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill on village schools, File P 649/8

Farewell letter to Sir Herbert Samuel from a student at Nazareth Government School, File P 654/1

Item Link

Teachers and pupils in the village of Majdal, TS 3020/43, PIO collection

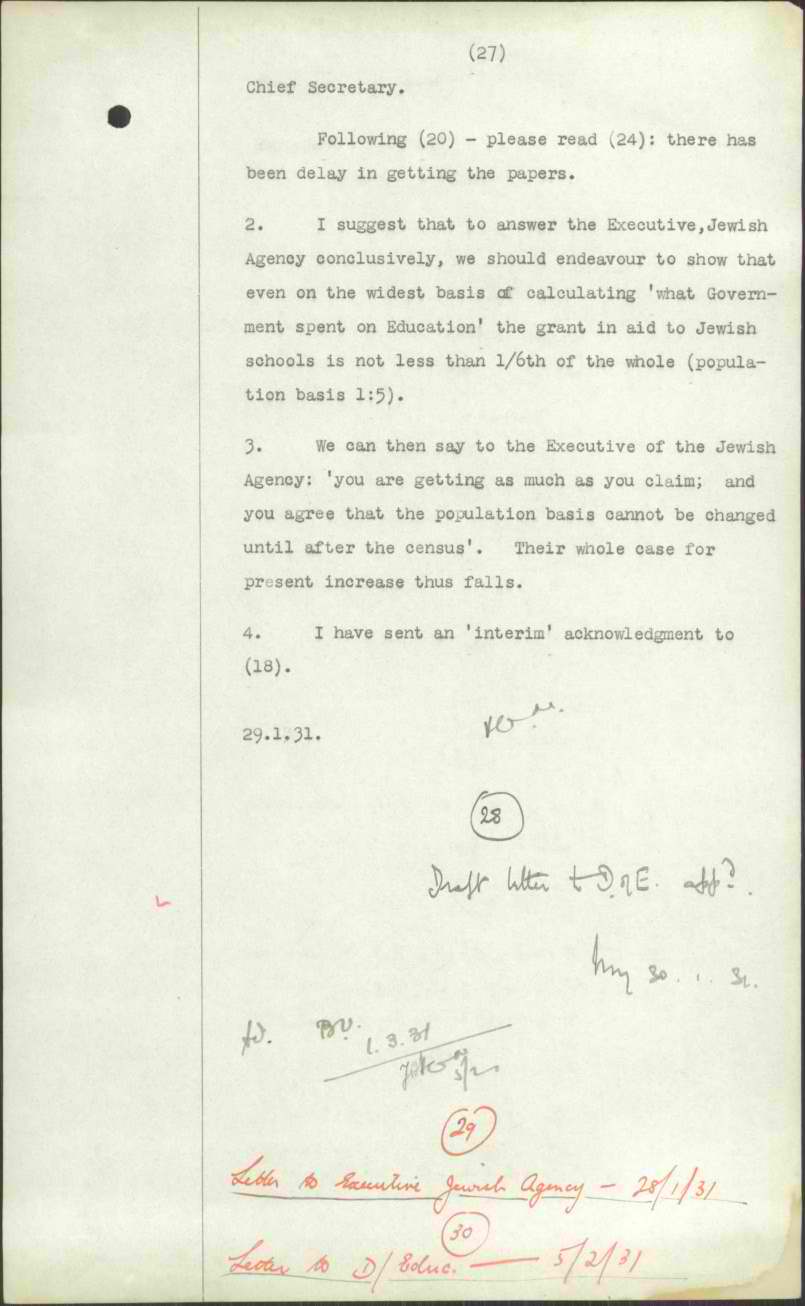

Jewish education developed separately because the language of study was Hebrew and education was seen as a tool for shaping the new generation in the Zionist spirit. Most of the schools were run by the elected Jewish body, the Vaad Leumi. In 1927 Lord Plumer recognized the Hebrew educational system as a public body entitled to participation in the budget according to its size in the population. The heads of the Education Department viewed this system as a “wasteful” body which was not properly run and accumulated deficits leading to unpaid salaries and strikes. They argued that Jewish education also enjoyed government services such as medical services and supervision of the matriculation exam.

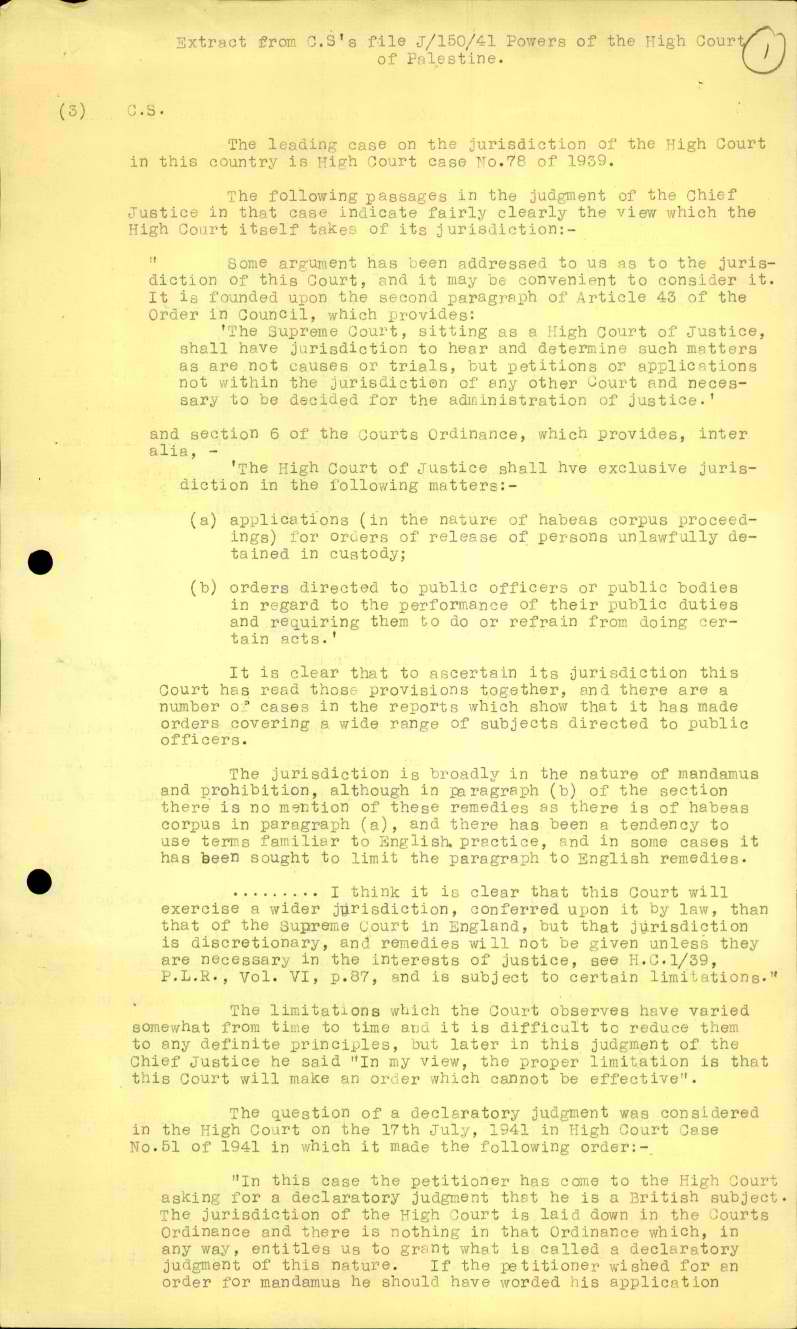

The legal system

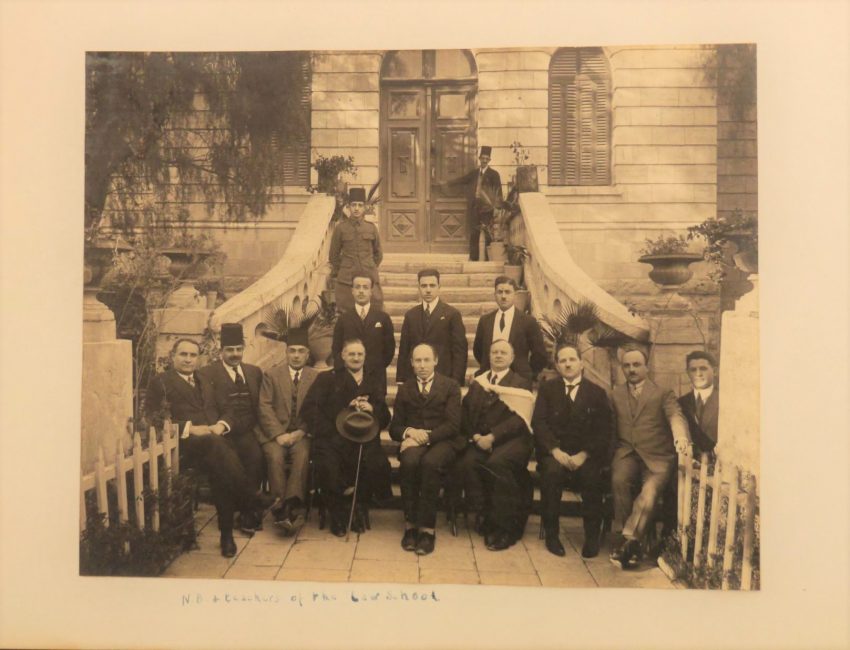

The Ottoman legal system was based on European foundations and on Muslim religious law, and it remained in force unless repealed. The structure of the system – the Magistrate’s Court, the District Court, and the Supreme Court – was laid down by the military administration. The Supreme Court helped to safeguard the rights of the citizen against the state. The number of local judges (mainly Arabs) grew, but the president of the Supreme Court was always British. The Attorney General dealt with cases ranging from mismanagement of a charity in Jerusalem to a land claim by the heirs of Sultan Abd el-Hamid, still pending in 1948. Only the first Attorney General, Norman Bentwich, was a (British) Jew.

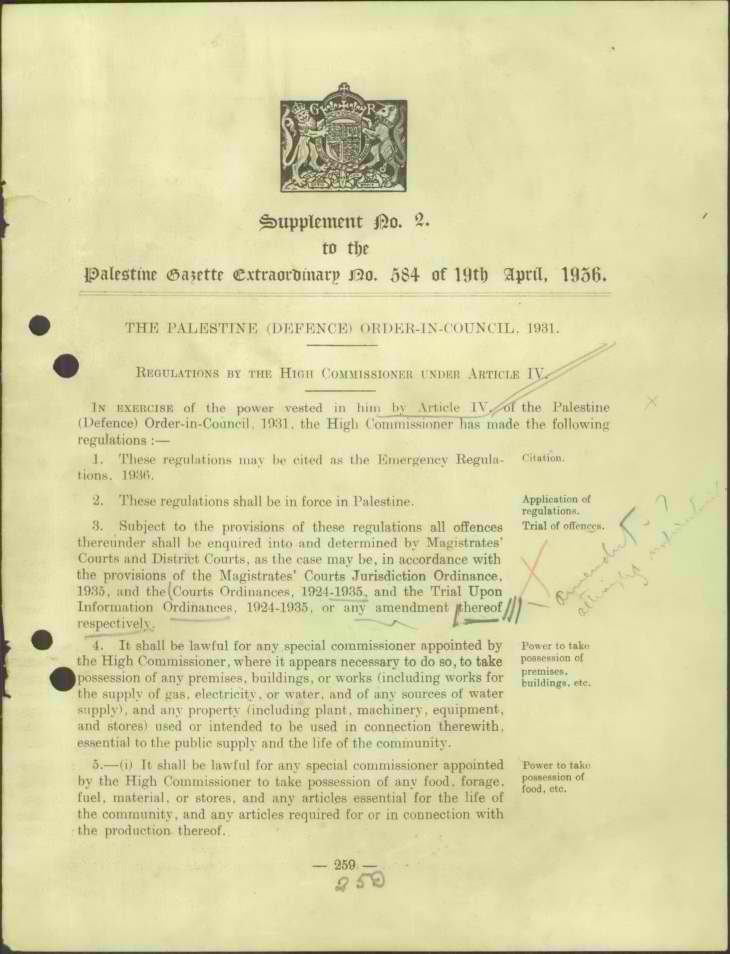

The adoption of English legal norms was halted by the Arab Revolt in 1936.

Attorney General Norman Bentwich (fifth from the R.) and teaching staff at the Law School. Private collection, courtey of Gur Bentwich

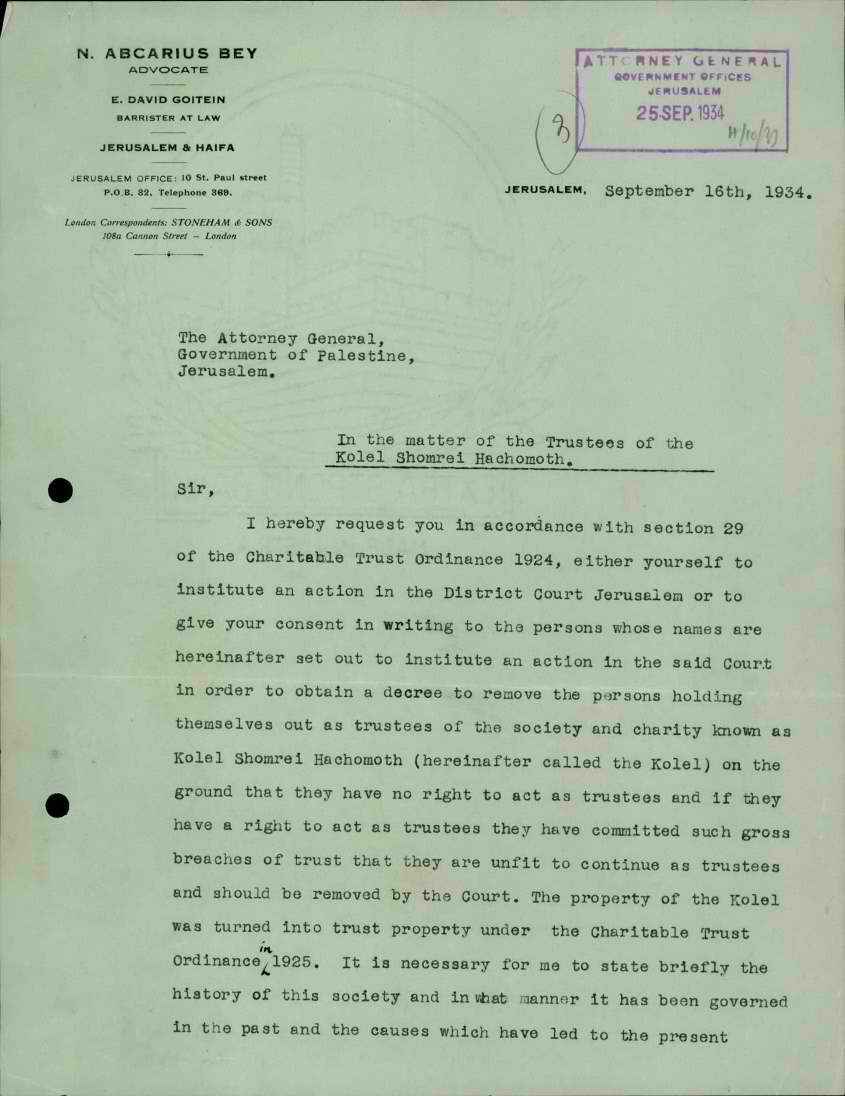

First page of a request that the Attorney General take action against the trustees of the Shomrei Hachomoth kollel (religious institution),

Item Link

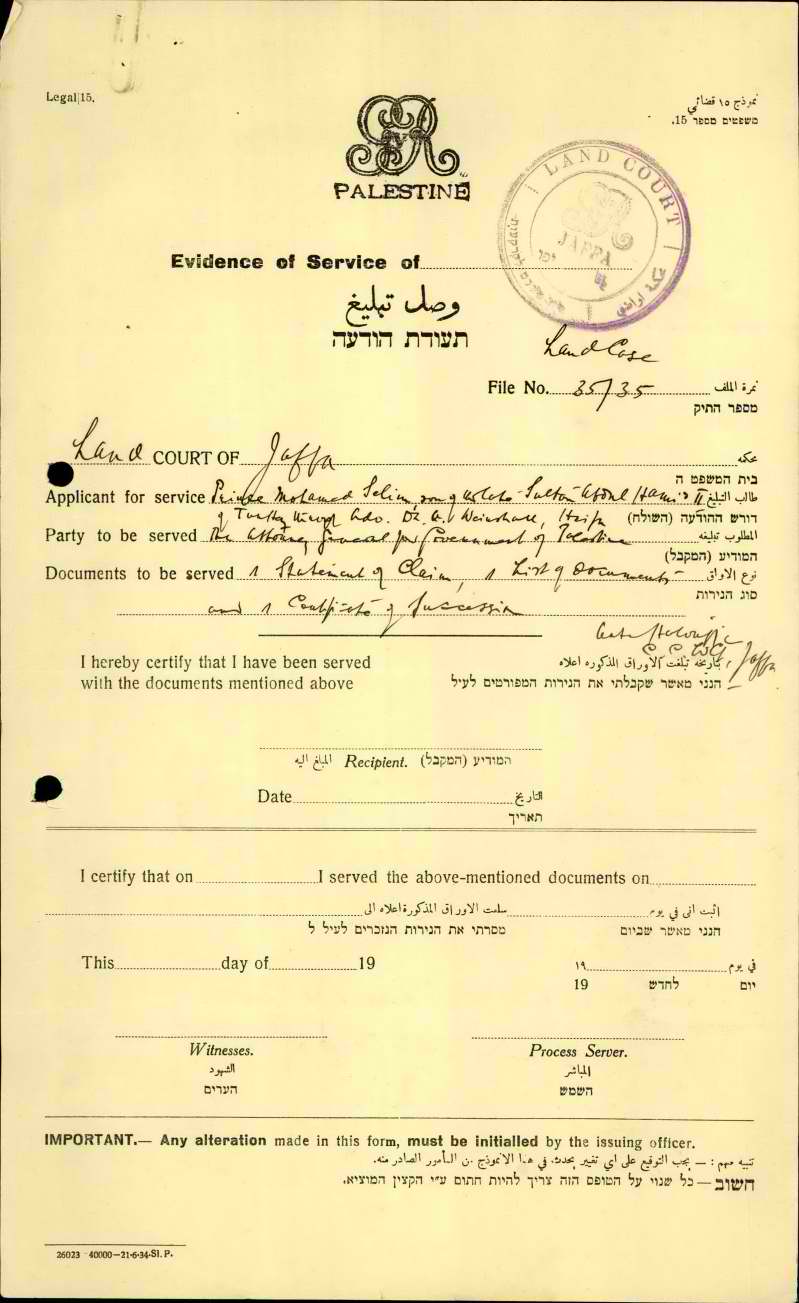

Service of documents to the Attorney General relating to the claim of Prince Mohammed Selim, son of the Sultan, to land on Mt. Carmel, File M 707/2

Item Link

The Emergency Regulations issued on the outbreak of the Arab Revolt, File M 4254/8

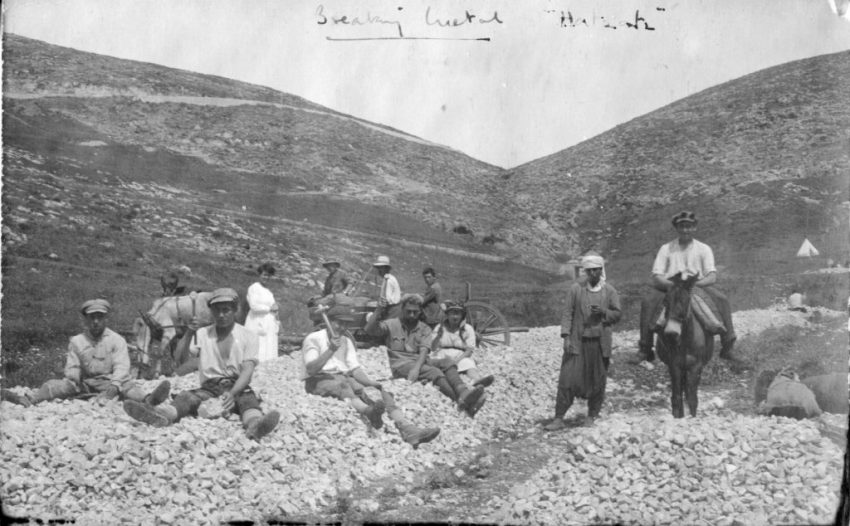

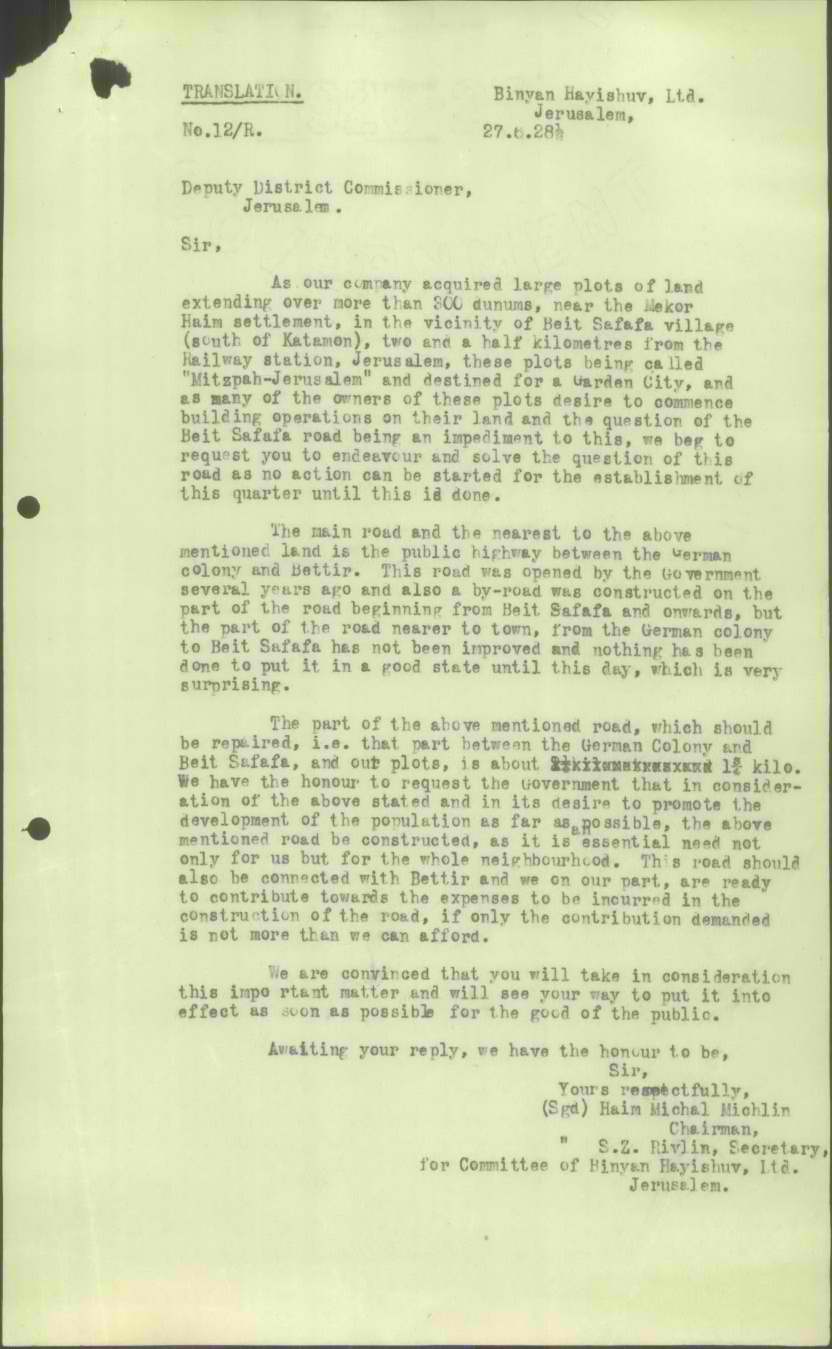

Item LinkRoad construction

During World War I many roads were built or improved by the Ottoman government. The British continued this work, making the roads the main transport system of Palestine. Government road works saved the workers of the Third Aliya from unemployment. During the economic crisis of 1926-8, public works also played an important role. Sometimes there was a combined Jewish-Arab interest in building a road: in a file on the road via the village of Beit Safafa to Bettir, which was opposed by the railways, we find an appeal from a Jewish building company to speed up work in order to found a new Jewish neighbourhood.

Private cars were rare and most public transport was based on buses.

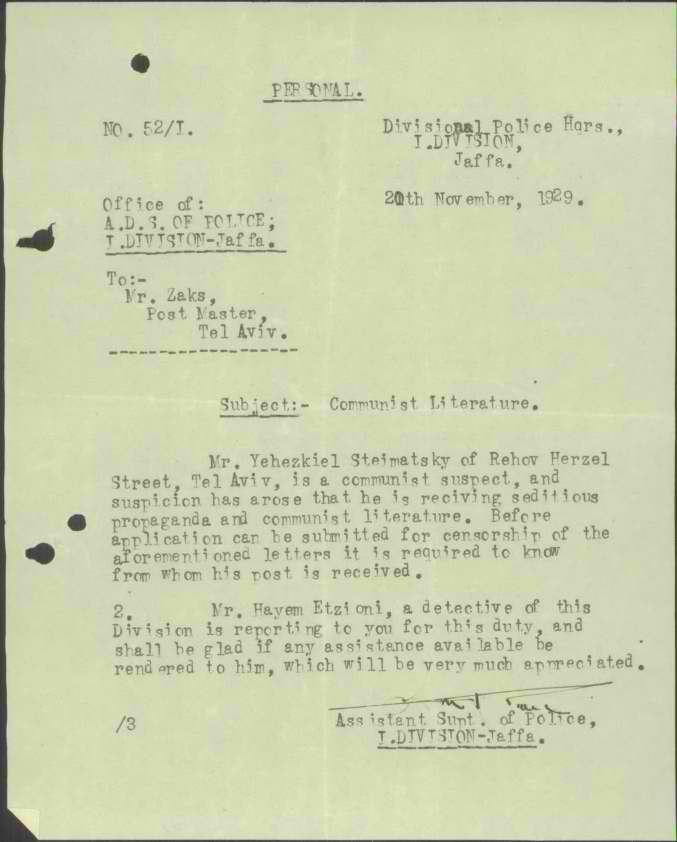

Communications: mail, telegraph and telephone

The Mandate government established a Department of Posts and Telegraphs in 1920 that replaced the Ottoman and foreign postal services that existed before World War I (Austrian, Russian and French postal systems). The postal department ran an efficient mailing system, joined by telegraph services and later by the telephone. Another lesser known service provided by the department was to help the police to monitor “subversive factors” – especially suspected Communists and those spreading Communist propaganda. The department was tasked with preventing entry into the country of “subversive material” and other harmful publications – mainly pornography. Later, Arab nationalist publications and some Jewish ones were considered dangerous.

Mandate-era post boxes near the Jerusalem Central Station, Wikipedia

Monitoring the post of Yehezkiel Steimatsky, one of the founders of the Steimatsky bookshop chain, File M 4159/1

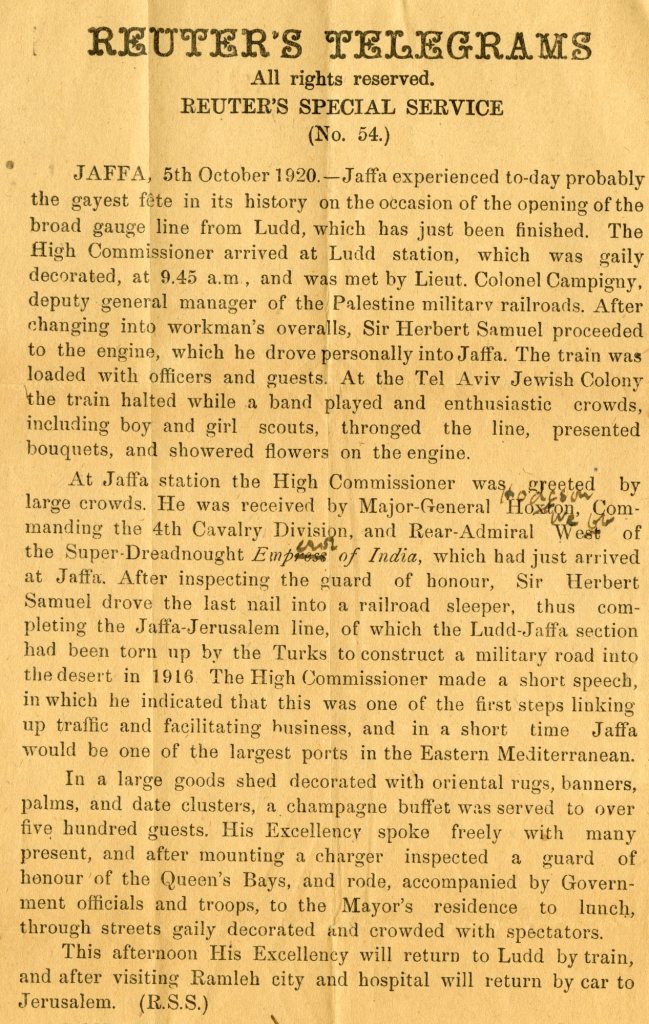

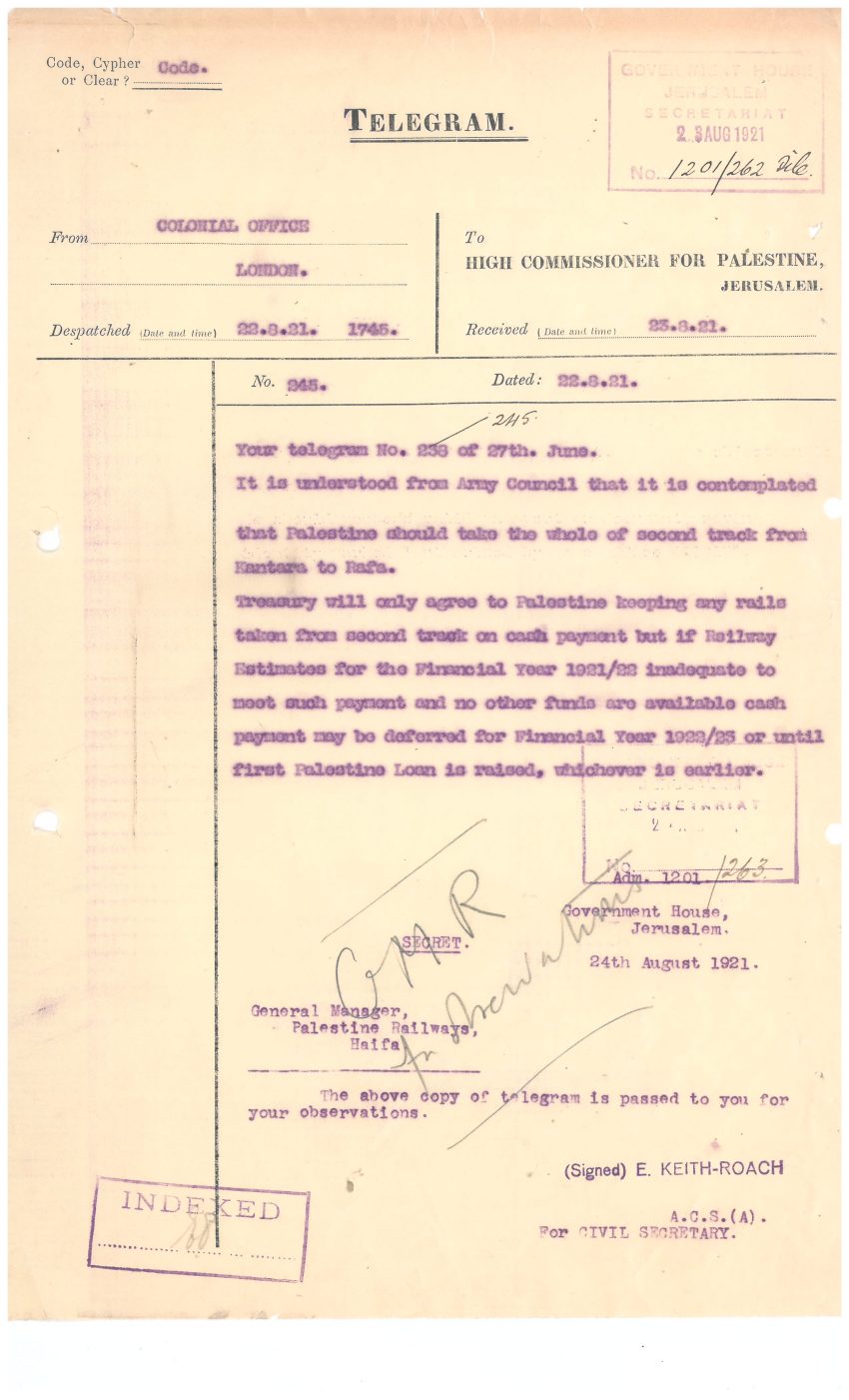

Item LinkThe railways

When they occupied Palestine, the British found the railways in poor condition. Tracks and rail bridges had been destroyed and some used a narrower gauge than that used in Britain. To go from Jaffa to Jerusalem, people had to change trains in Lod. One of Samuel’s first actions was to widen this track, completed in October 1920. The train was connected to Egypt by a line to Kantara. When the Palestine railways wanted to use some rails which were being dismantled, the Colonial Office sent a telegram to Samuel on the Treasury’s refusal to pay and its demand that the Palestine government do so.

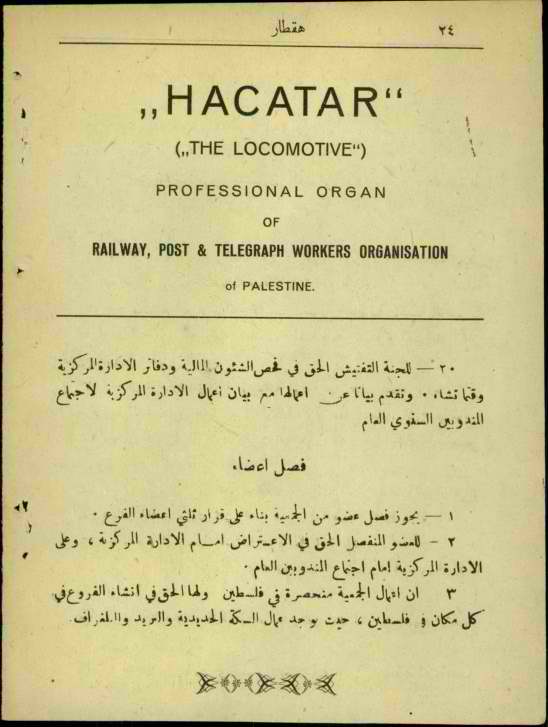

The Histadrut (General Workers’ Union) established the “Railway Workers’ Federation” which was also for Arab workers and published a magazine called “The Locomotive”, partially in Arabic.

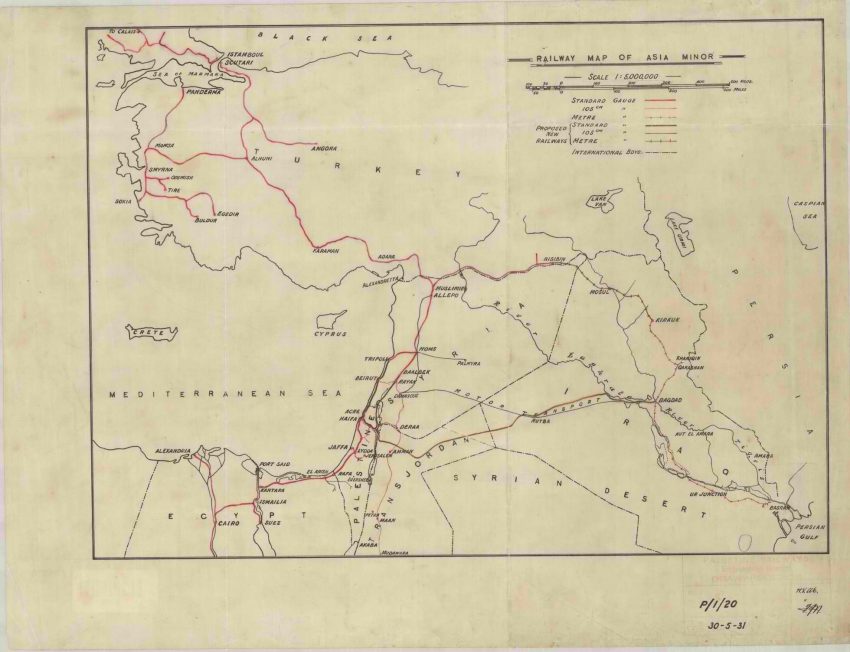

Railway map of the Middle East, File P 4204/4

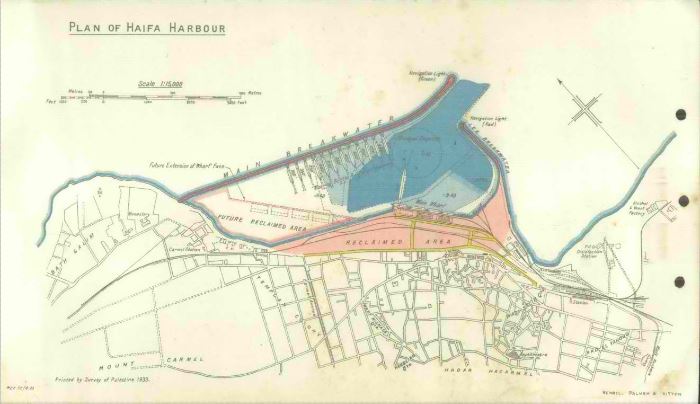

The new Haifa port

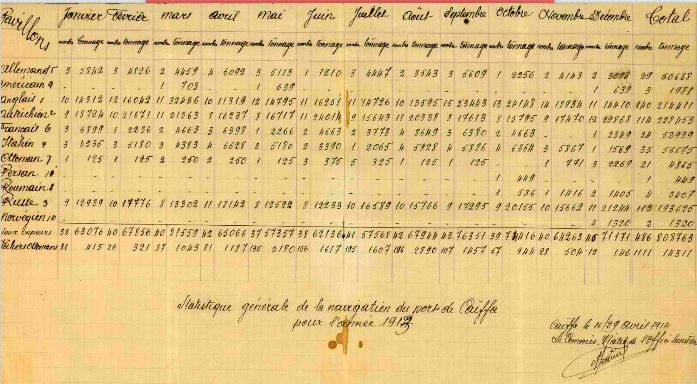

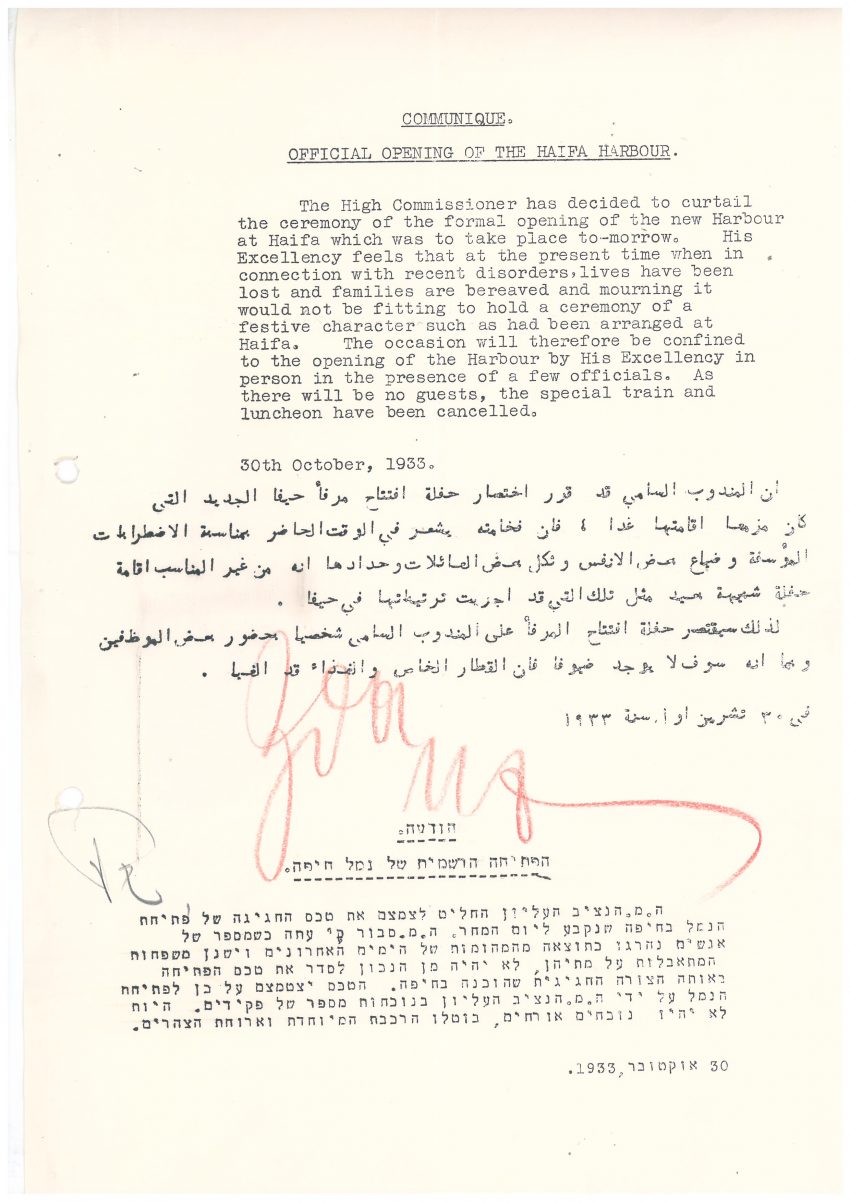

As early as 1898, Theodore Herzl proposed to build a modern port in Haifa to serve the new large steamers which needed deeper water. Haifa has a natural bay, and the establishment of a branch of the Hejaz Railway in 1905 increased traffic to the port. In his letter to Allenby, Samuel also proposed a new port, but construction only began in 1927. The port opened on October 31 1933. The day before, High Commissioner Sir Arthur Wauchope issued a statement that the opening festivities would be cut due to the Arab riots in Jaffa. A special booklet was printed for the opening.

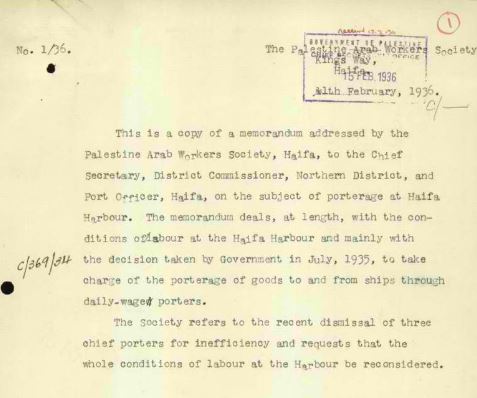

Jews and Arabs worked side by side in the port. Initially, porters were employed by contractors, but in July 1935, the port moved to direct hire on a daily basis. The Arab Workers Union sent a letter of protest.

High Commissioner Wauchope's announcement of a low key opening ceremony, File P 528/4

Item Link

Plan of the harbour, from the booklet marking the opening of the port, File P 4189/13

Item Link

Summary of a protest letter about working conditions at the port, File M 37/3

Item LinkIndustry

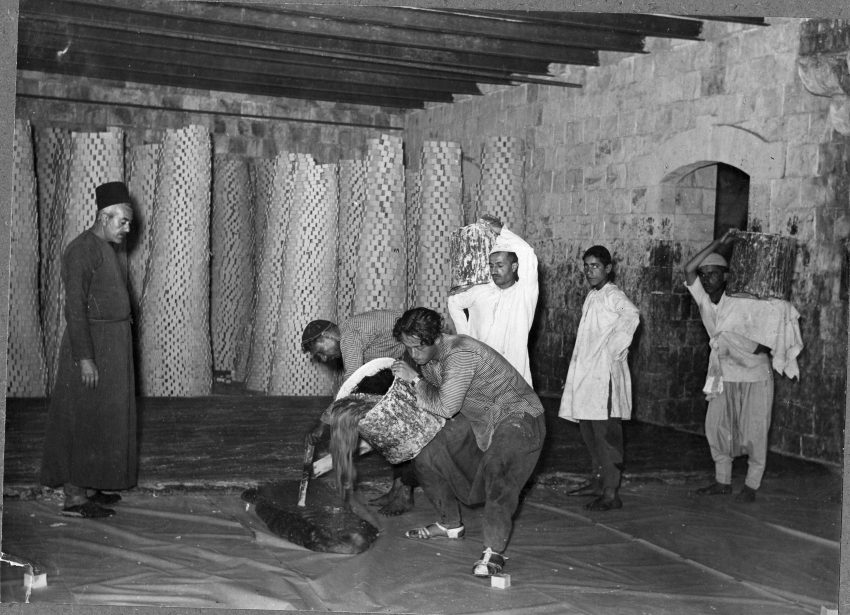

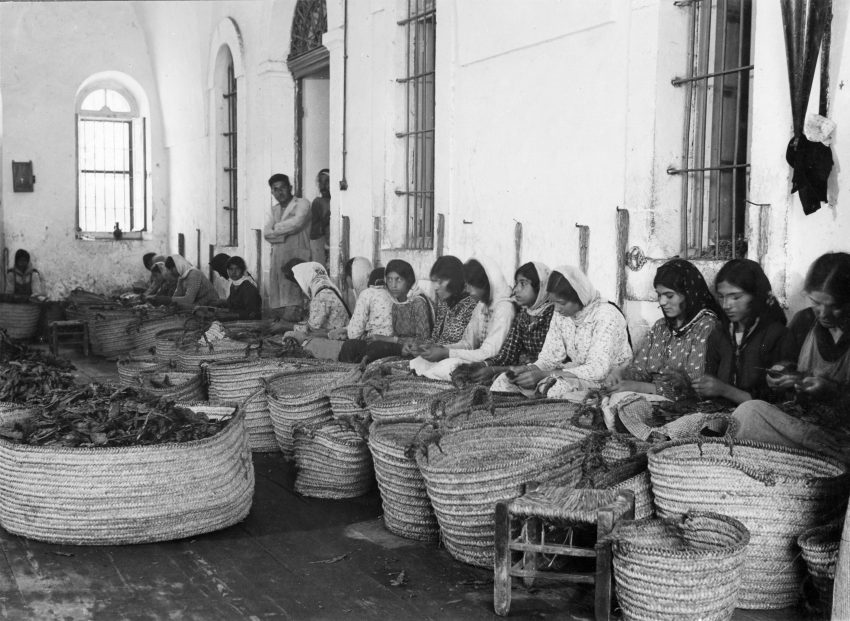

In 1918 there was no significant industry in Palestine, with the exception of traditional industries such as olive oil or soap production concentrated in Nablus and Hebron. The Mandate government and increasing Jewish immigration helped to launch various industrial ventures, some of which exist to this day. Among them were the canning of fruit and vegetables, heavy industry (mainly in Haifa), engineering works, textiles and more. In the Arab community, stone quarries flourished due to the great increase in construction, but this industry was damaged during the 1936 uprising.

Soap manufacture in Nablus, PIO collection, File TS 3012/9

Item Link

Women workers sorting tobacco leaves at a cigarette factory in Nazareth, PIO collection, File 3020/87

Item Link

Women workers in the "Elite" chocolate factory in Ramat Gan, Zoltan Kluger collection, TS 10388/3

Item Link

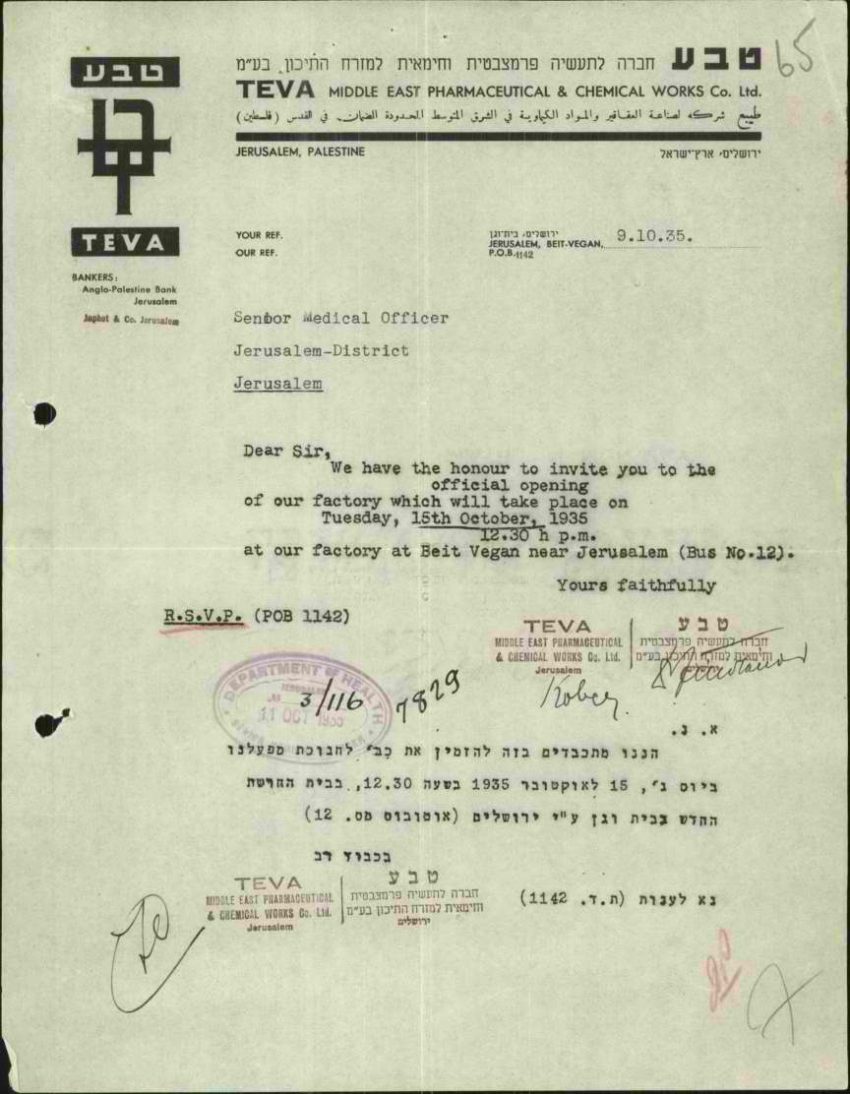

Invitation to the opening of the "Teva" pharmaceutical factory in Jerusalem, File M 6548/25

Item LinkAgriculture and forestry

The establishment of the Mandate helped to rehabilitate agriculture in Palestine which had been severely damaged during World War I. The confiscation of crops by the Turkish army, the devastating locust plague in 1915, and fighting in agricultural areas damaged production. Destruction of forests caused land erosion. A Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry was set up which worked to promote the major crops – citrus, cereals, olives etc., replanting the forests (in collaboration with the Jewish Agency and the JNF) and strengthening the fisheries. The department was also responsible for an advanced veterinary service to fight animal disease, and for developing new seeds and plant nurseries.

Fishing boat, PIO collection, File TS 3024/127

Item Link

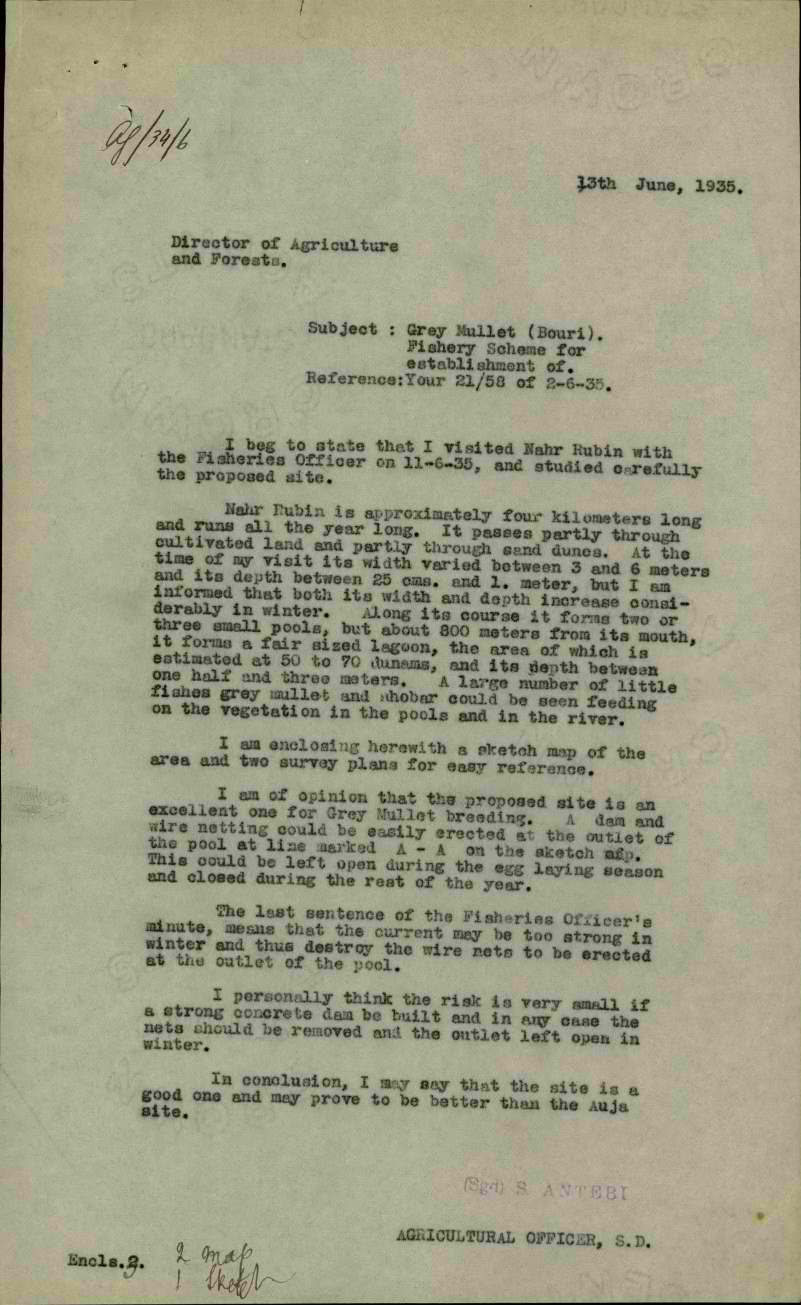

A plan to raise grey mullet (bouri) fish at Nahal Rubin, near Nahal Soreq, File M 657/17

Item Link

Packing citrus, PIO collection, File TS 3020/85

Item Link

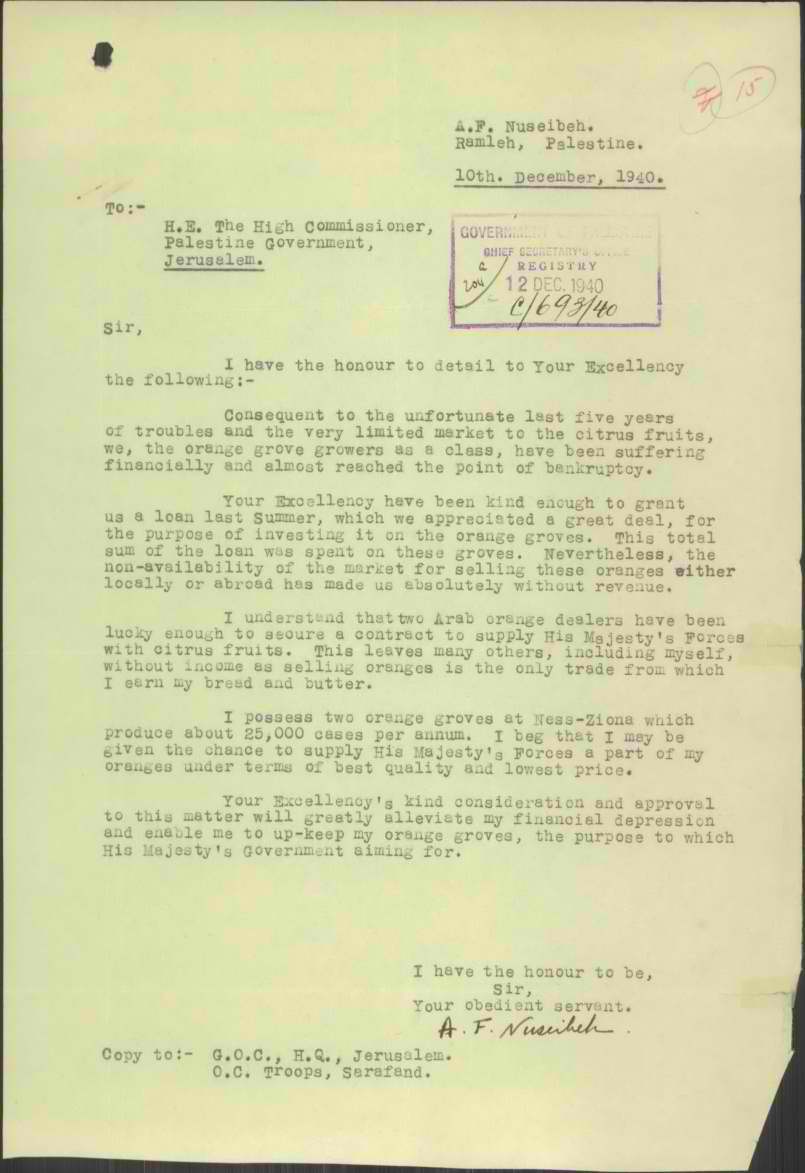

Anwar Nusseibeh writes to the High Commissioner: request for inclusion in a contract to sell citrus to the Army, File M 66/17

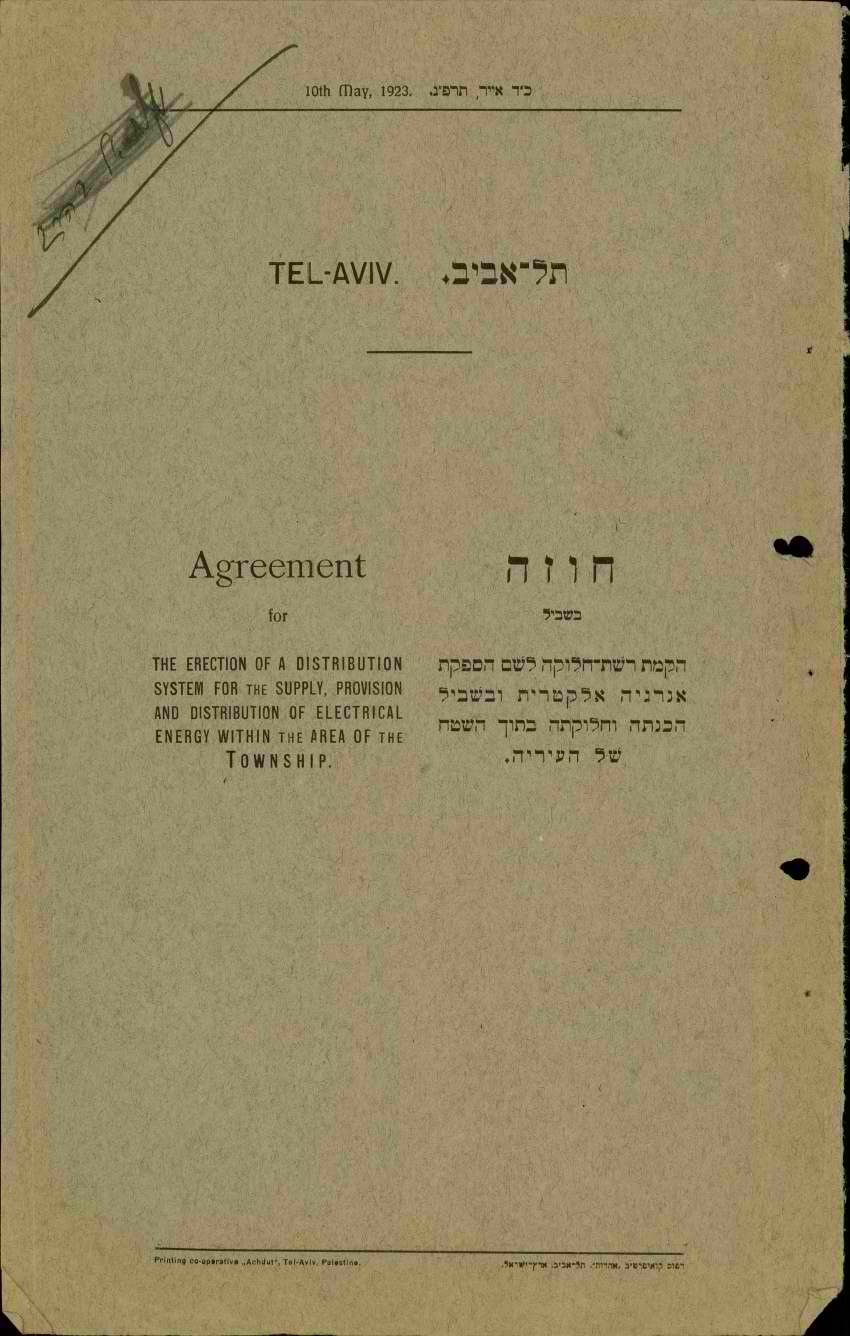

Electric power

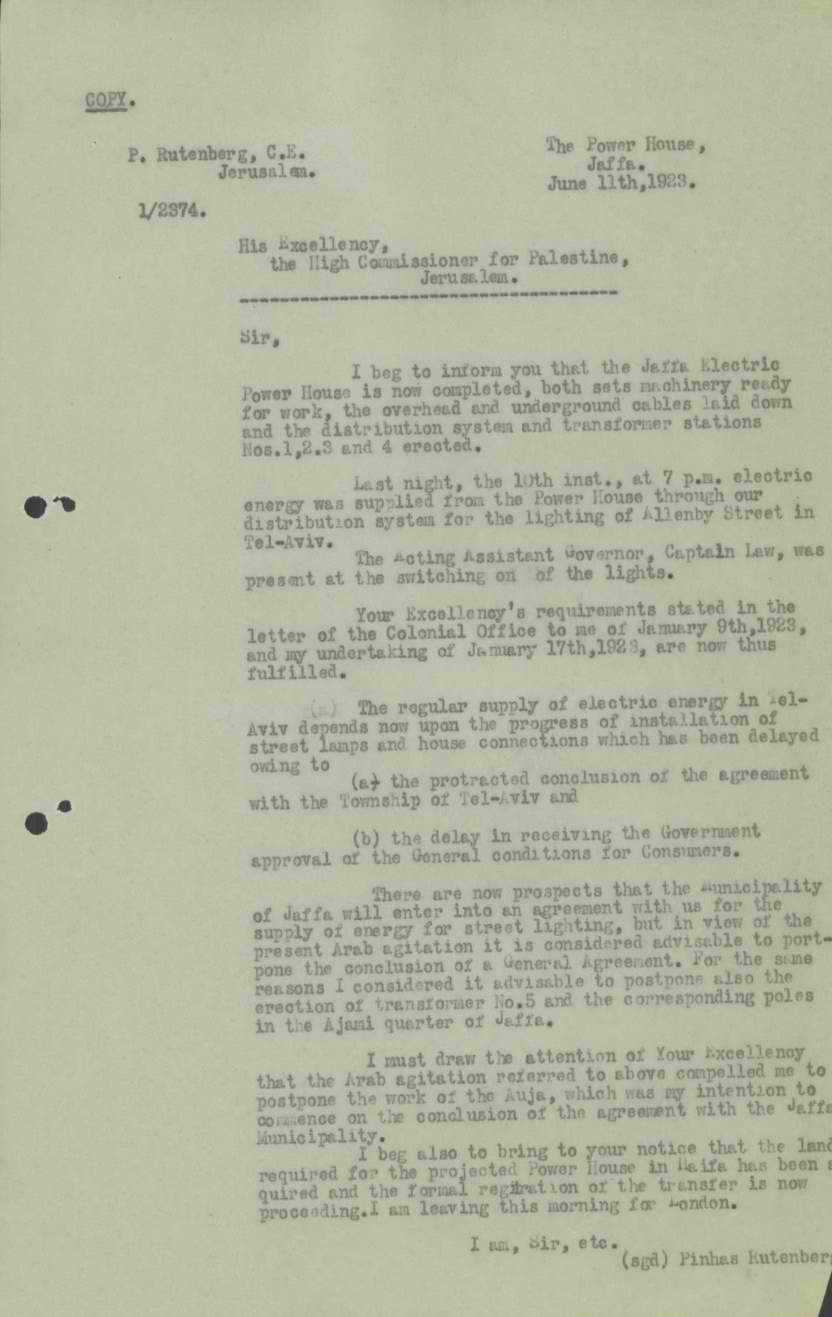

In his letter to Allenby, Samuel mentioned Pinhas Rutenberg, a Jewish engineer and ex-revolutionary from Russia. Supported by the Zionist Organization and Baron Edmund de Rothschild, Rutenberg submitted to the government a survey on utilizing hydroelectric power. The plan would benefit both Arabs and Jews, but after the May 1921 riots, Samuel feared Arab reaction. Nevertheless, Rutenberg received two exclusive concessions to all the water resources in the country. The first was for Jaffa, and he was to build a hydroelectric power plant near the Aujah River (the Yarkon). Due to opposition from the Christian-Muslim Association of Jaffa and the high price of land, Rutenberg built a diesel-powered plant instead. On June 10, 1923, Allenby Street was lit up. Eventually the Jaffa municipality agreed, and in November 1923, Jerusalem Boulevard was connected up.

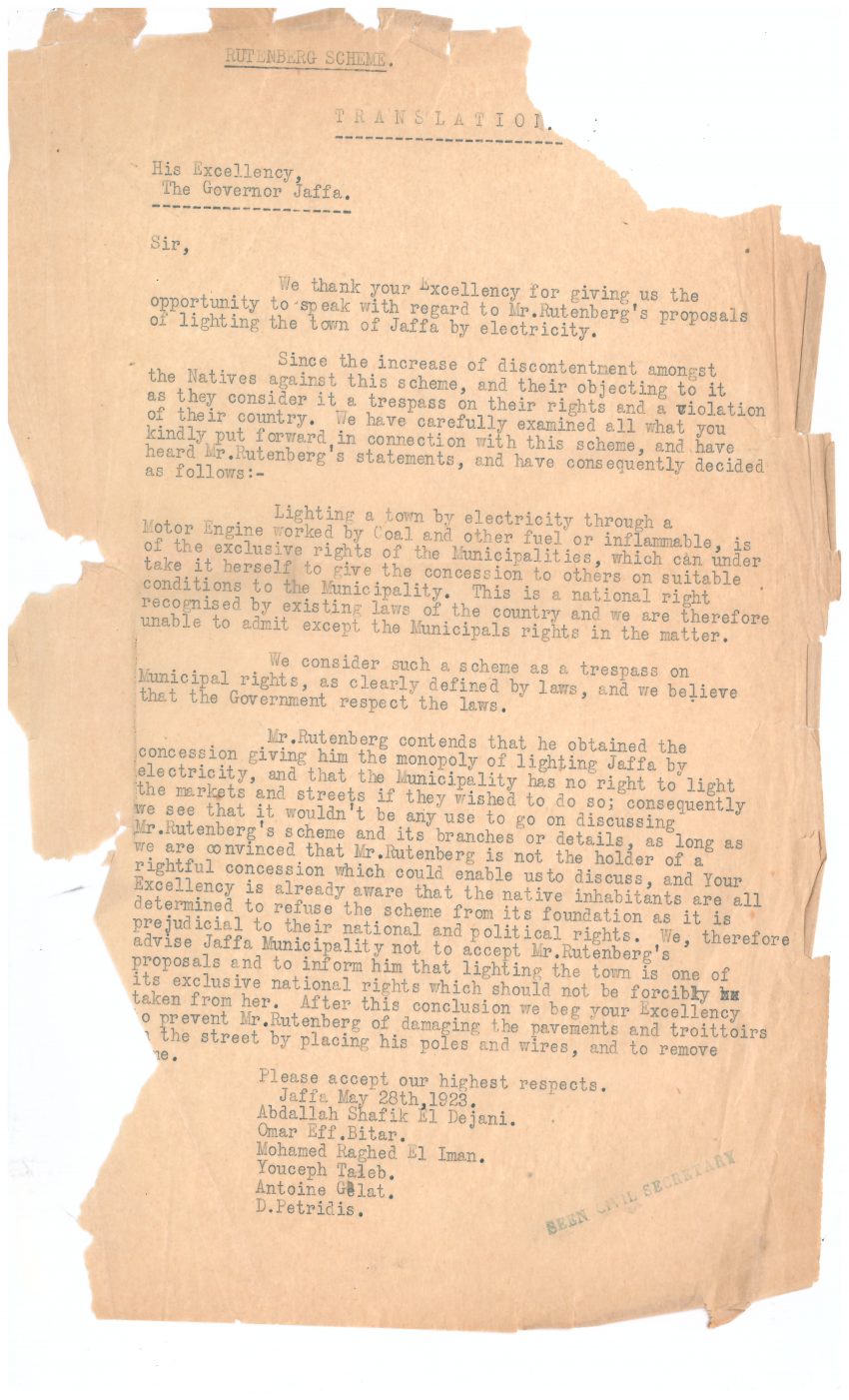

Letter of protest against Rutenberg's plan by a committee of Jaffa residents, File M 9/10

Item Link

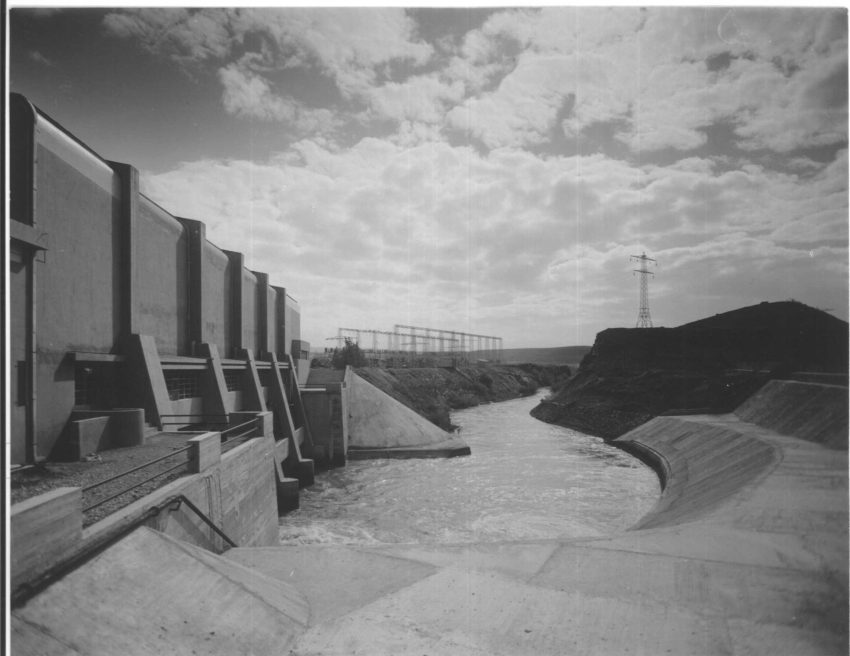

The Jordan River concession: Power plant at Nahariyim, opened 1932. Historical Archives, Israel Electric Corporation

The establishment of the police

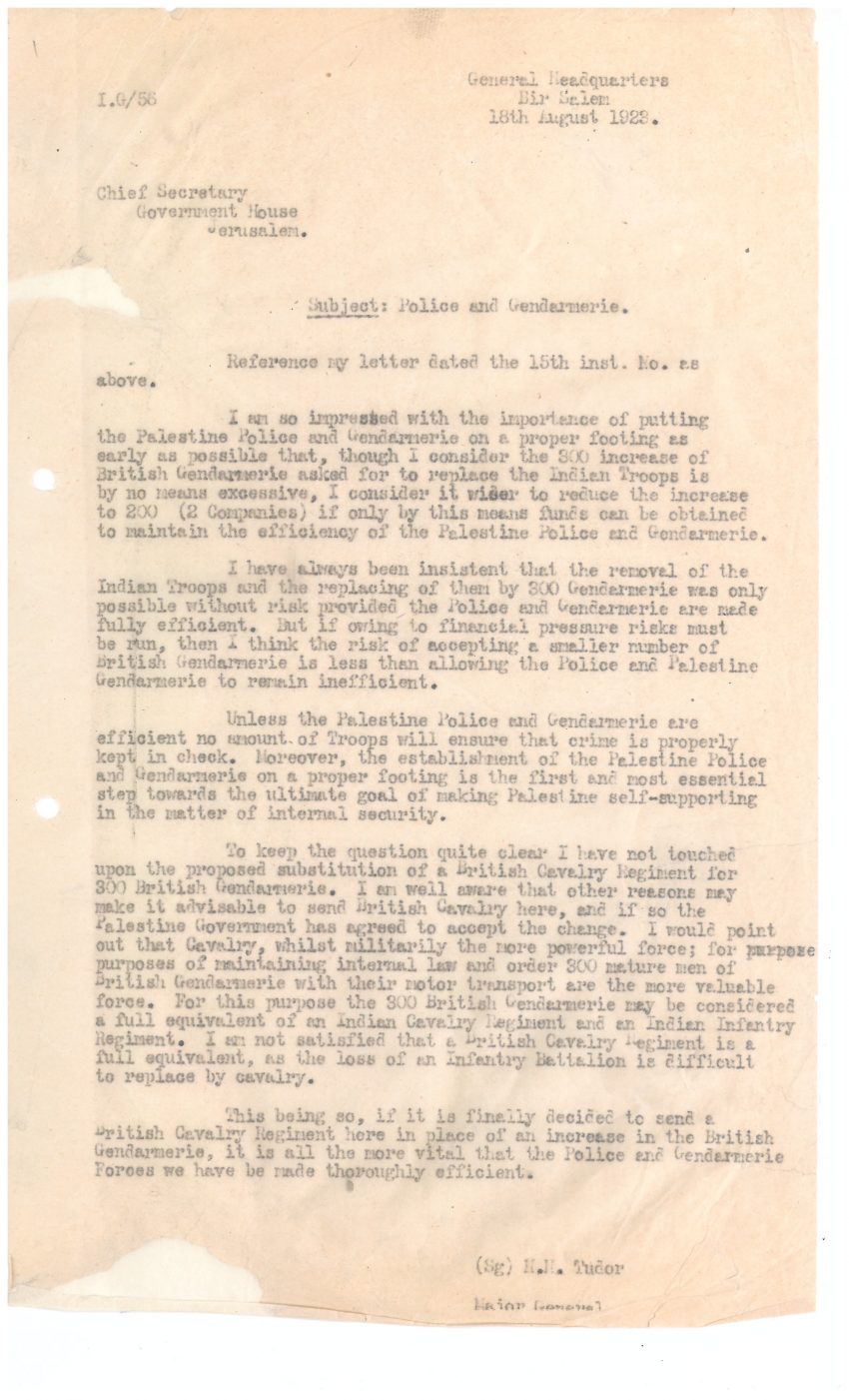

The Palestine Police was established in 1921 after a failed attempt to establish a gendarmerie – a semi-military police force – in 1919. The nucleus of the new force came from Ireland and belonged to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). This force too had semi-military characteristics but it gradually changed, until by the mid-1920s it became a regular police force using local auxiliaries – Ghaffirs or special police, known in Hebrew as “Notrim”. A Criminal Investigation Department was also set up. The Palestine Police played an important part in shaping the image of the British Mandate in the eyes of the residents – for better or worse.

General Tudor, the first commander of the Palestine Police, on ways to improve efficiency, File M 4784/39

From the standing orders: adoption of the Turkish kalpack as regulation police headgear

Palestine Police unit drilling in kalpack hats, PIO collection

Item LinkHealth

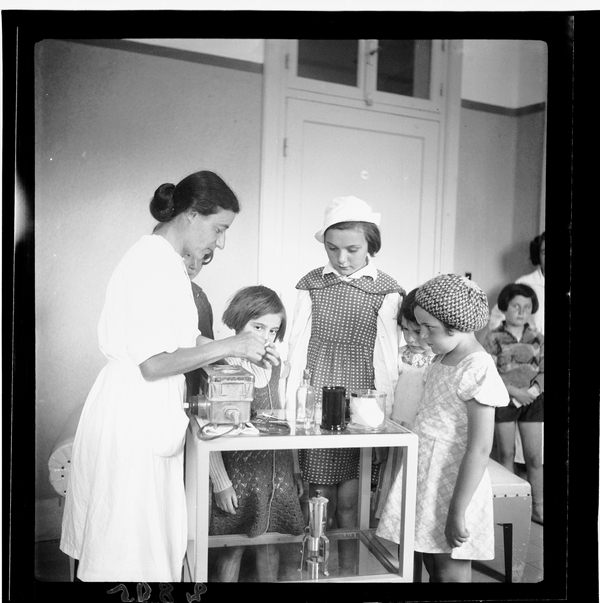

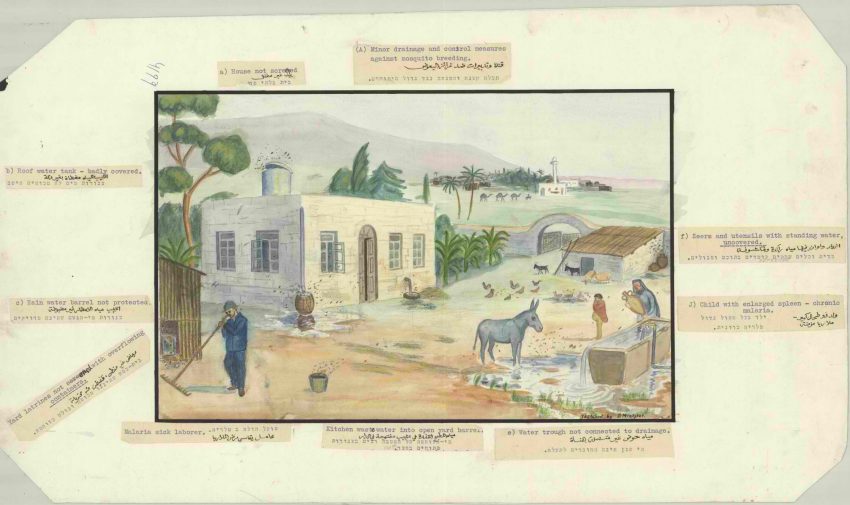

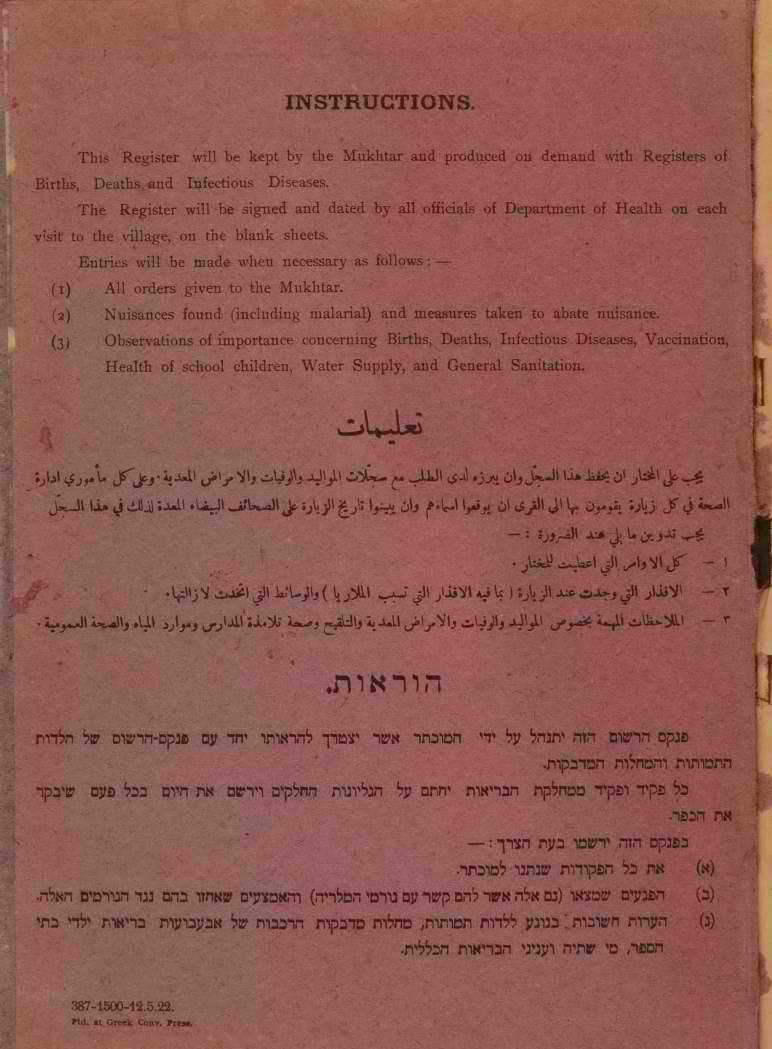

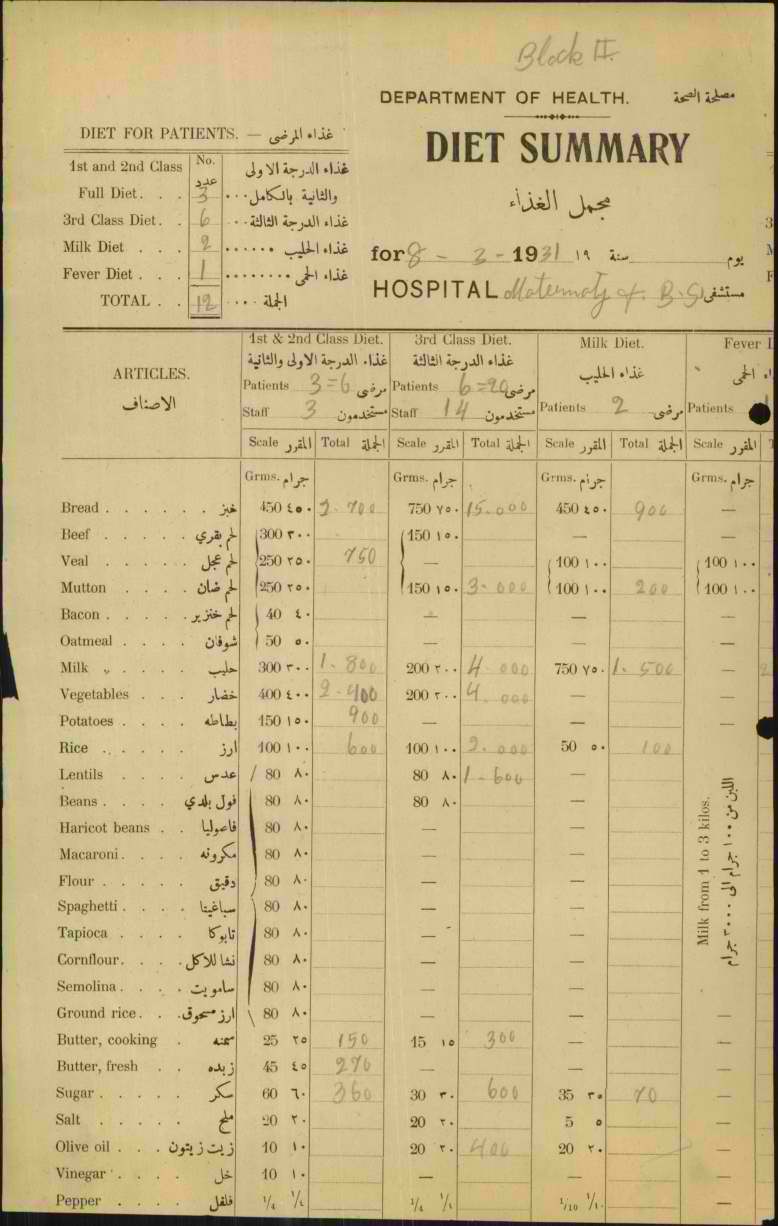

Under Turkish rule there were medical services in the cities, especially Jerusalem, often funded by foreign bodies, but few for the rural population. The Military Government set up a health department to treat infectious diseases. The Mandate Health Department continued its work in preventive medicine, licensing and sanitation. The war on malaria, one of the main aims of the government, included draining the marshes, but also ensuring that any standing water was drained or covered. Since health received only 3% – 5% of the budget, expensive services like hospitals and clinics were limited. The Jewish public looked after itself through the health funds and “Hadassah”. Government hospitals mainly served British workers and the Arab public. Only third-class care was free.

Poster on defence against malaria-bearing mosquitos, File CR 459/1

Item Link

Diet menu for 1st, 2nd and 3rd class patients in a government hospital, M 6553/4

Item Link

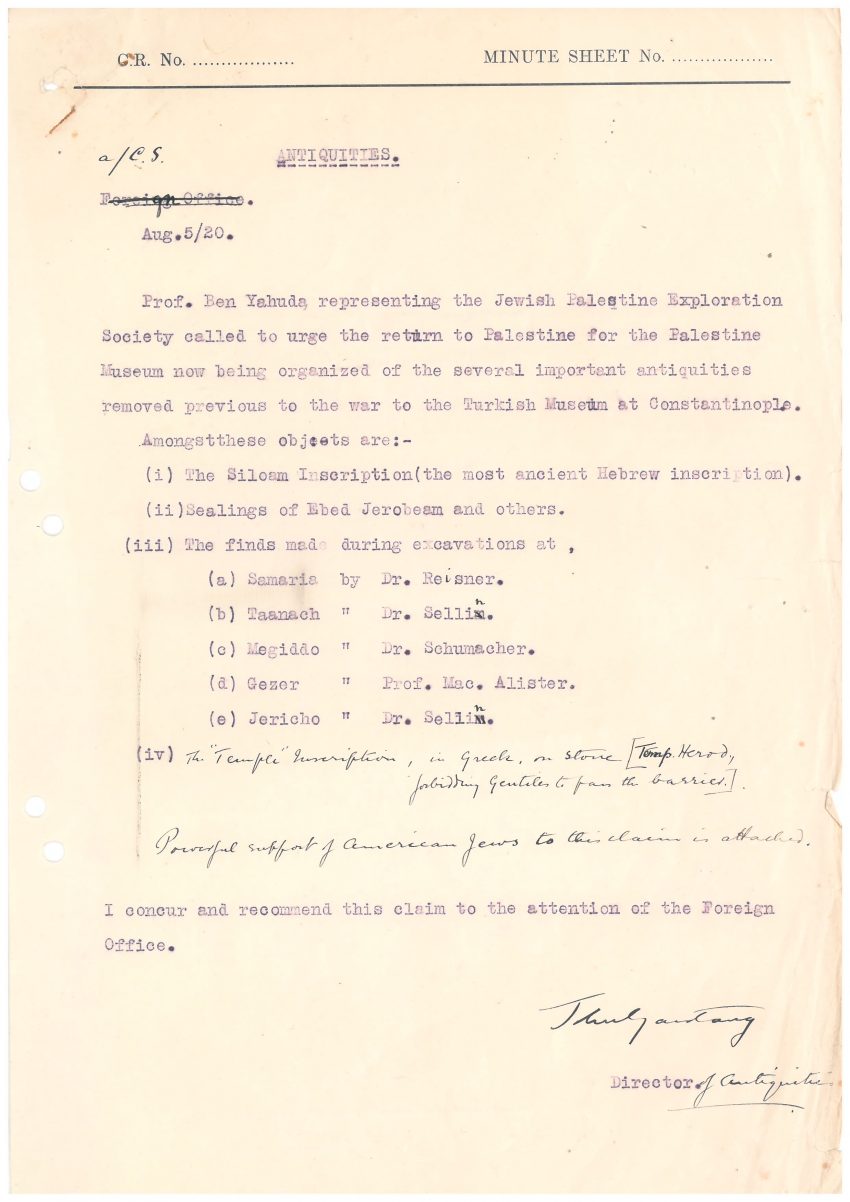

Antiquities Department

One of the first steps taken by the British after conquering Jerusalem was governor Ronald Storrs’ declaration on the preservation of the Old City and its environs. Storrs also founded the interfaith Pro-Jerusalem Society. In August 1920 Samuel wrote to the Foreign Office about the appointment of Professor John Garstang of the British School of Archaeology to establish an antiquities department. Monitoring excavations and preventing the export of antiquities were even required by the Mandate.

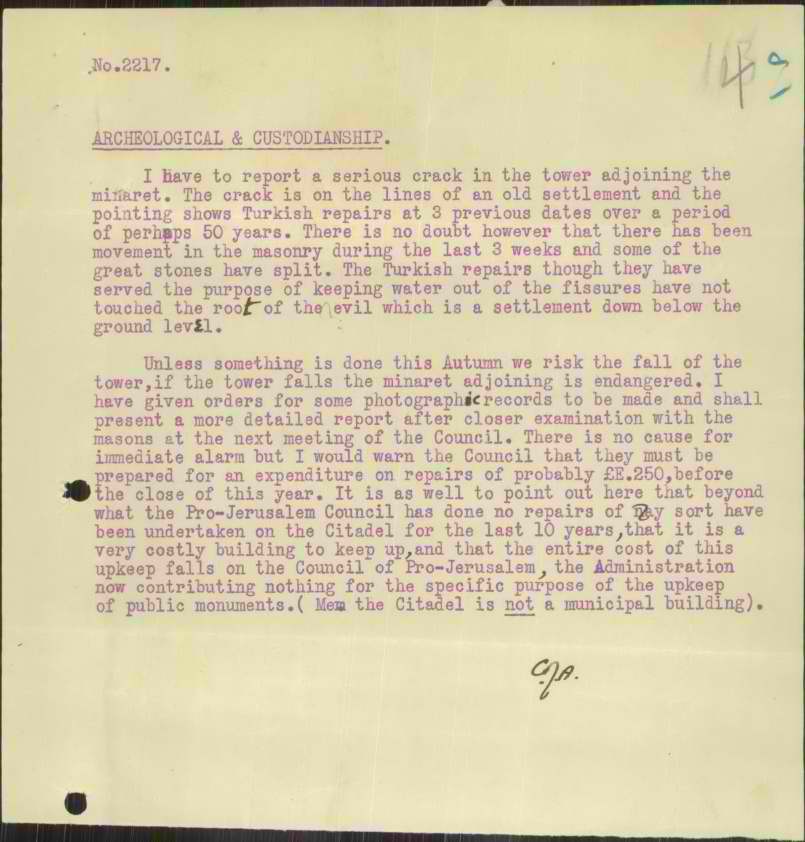

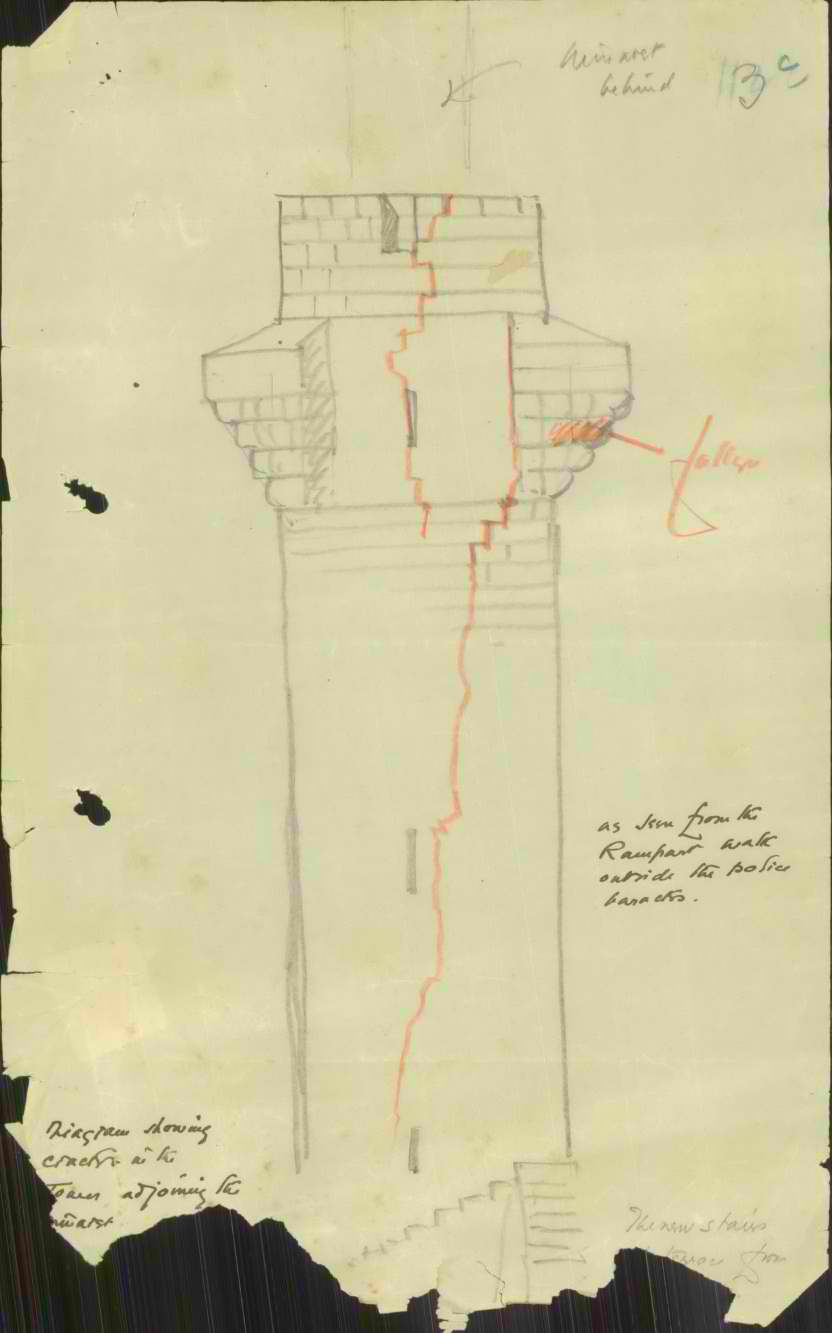

The Citadel in Jerusalem was a major site initially run by “Pro-Jerusalem”. Because of its poor condition, plans were made to demolish part of it to build a museum. Eventually, a new museum was built.

Garstang supports the claim of Jewish researchers for the return of important finds from Turkey, File M 2/2

Item Link

Letter from the Civic Advisor, Charles Ashbee, to the Public Works Department, on the crack in the Citadel in Jerusalem, File M 4145/4

Item Link

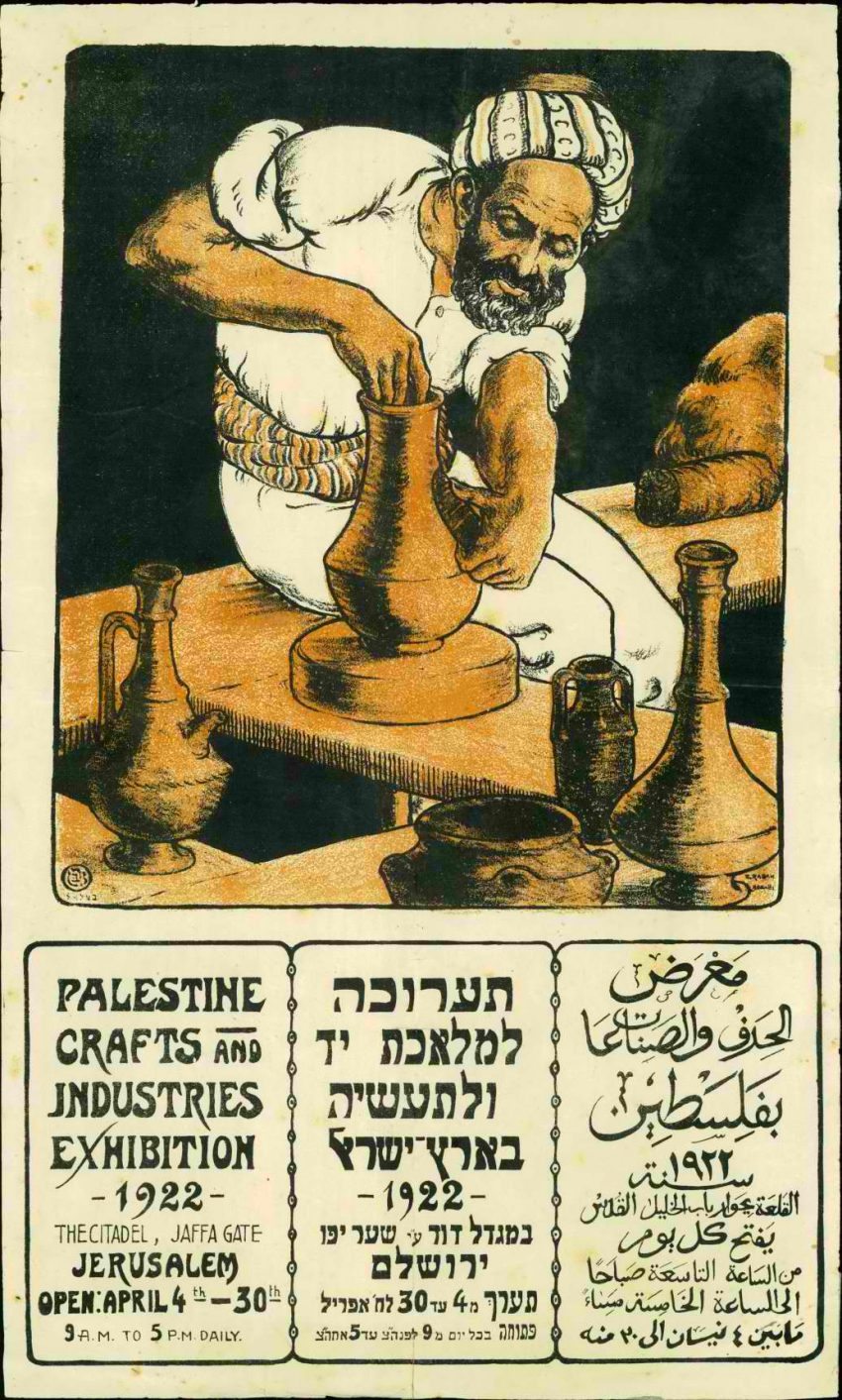

The Citadel also served as an exhibition centre and a museum of folk art. File P 654/1

Item LinkEpilogue

Sir Herbert Samuel left Palestine in July 1925. He wanted to stay on as a private citizen, but his successor, Lord Plumer, objected. Samuel believed that he had laid the foundations for the development of a modern society. But lack of money held up many of his plans.

According to the Babylonian Talmud (Tractate Shabbat), the sages once debated whether Roman rule benefited the people. “R. Yehuda… said: How fine are the acts of this nation: They established markets! They established bathhouses! They established bridges!… R. Shimon [bar Yohai] answered and said, “Everything they established, they established only for themselves: They established markets – to put prostitutes there; bathhouses – to pamper themselves; bridges – to take tolls.” Who was right?

Near the end of his term of office, members of the American Colony in Jerusalem gave a parting gift to Samuel – a photograph album called MIZPAH. You are invited to browse the exhibition dedicated to this album.

See also the collected papers of Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a leader of the workers’ movement and the Vaad HaLeumi.

More links to the ISA catalogue

Herbert Samuel Collection (documents)

Herbert and Edwin Samuel Collection (photographs)

Palestine Government departments and other institutions ( גופים מנדטורייםMandatory bodies)

Curated by Louise Fischer

With Arnon Lammfromm and Shlomo Mark

- Start Exhibition

- Exhibition link

What are you looking for ?

Type your question

-

Popular searches

-

Popular People

-

Popular Government Bodies