א.1 | Introduction

In June 1992, elections for the Knesset were to be held in Israel, and Yitzhak Rabin, the Labour Party leader, pledged to reach an agreement with the Palestinians within six to nine months. In April 1992 Yossi Beilin, head of the dovish “Mashov” group in the Labour Party and a prominent supporter of Shimon Peres, Rabin’s rival, met with Terje Rød Larsen, head of the Norwegian Institute for Social Sciences (FAFO) which had carried out research on Palestinian society. Larsen’s wife, Mona Juul, worked at the Norwegian Foreign Ministry. According to Beilin in his book “Touching Peace” (1997), they agreed on a plan to establish an unofficial channel for talks with the Palestinians after the elections in order to advance the peace process.

The Labour Party won the elections and Rabin was elected Prime Minister. At that time, the talks with Palestinian representatives from Judea and Samaria and the Gaza Strip that began following the Madrid Conference (1991) were still being held in Washington. In the talks, an interim agreement based on autonomy, elections for a Palestinian Authority and negotiations on a permanent agreement after a transitional period were discussed. Disagreements emerged regarding the size of the Palestinian Council and its powers, reflecting the Palestinian fear that the interim agreement and the establishment of autonomy would become the permanent solution, as planned in Menachem Begin’s original autonomy proposal. Without open support from the PLO and its chairman, Yasser Arafat, there was no real progress in Washington.

Rabin’s speech in the Knesset on presenting his government, 13 July 1992

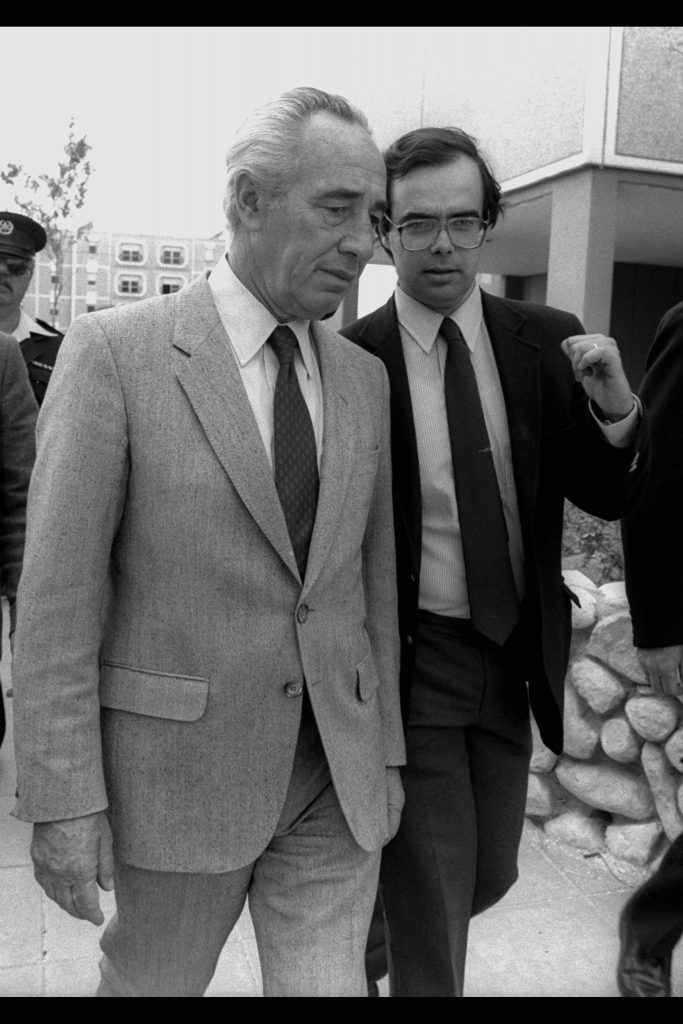

Prime Minister Rabin and Shimon Peres had competed for many years for the leadership. After the victory, Peres became Foreign Minister and they reached an agreement on joint activities, but Rabin excluded Peres from the main channels of the peace process – contacts with the Americans on an agreement with Syria and the talks with the Jordanians and the Palestinians in Washington. Peres and Beilin, who became Deputy Foreign Minister, were left with the field of multinational talks on regional issues such as the water problem and the Palestinian refugees. To expand the participation of the Palestinians in these talks, Peres turned to Egypt. In November 1992, Peres proposed to President Hosni Mubarak to establish autonomy in Gaza first before expanding the process to Judea and Samaria. (The Egyptians made this proposal back in the 1970s, after the signing of the Camp David Accords). Arafat did not reject the idea.

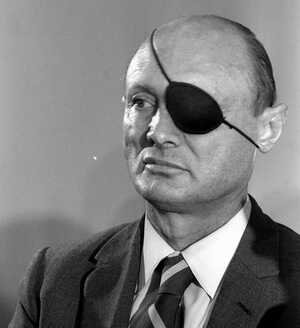

Dr. Yair Hirschfeld, 2018. Pthotograph: Wikimedia

In December 1992, Dr. Yair Hirschfeld, an Israeli academic and Beilin’s partner in the Economic Cooperation Fund (ECF), a research body to promote peace that sought to influence government policy, met in London with Abu Ala (Ahmed Qurei), one of the leaders of the PLO and the head of its economic department, and Afif Safieh, the PLO representative in the UK. Abu Ala came to London as part of the steering committee of the multinational talks, and the meeting was made possible following contacts between Beilin and Hirschfeld and the Palestinian activist Hanan Ashrawi and Larsen. This meeting led to the opening of a dialogue between Hirschfeld and his student and fellow-academic, Ron Pundak, a former member of the security establishment, and the PLO in January 1993.

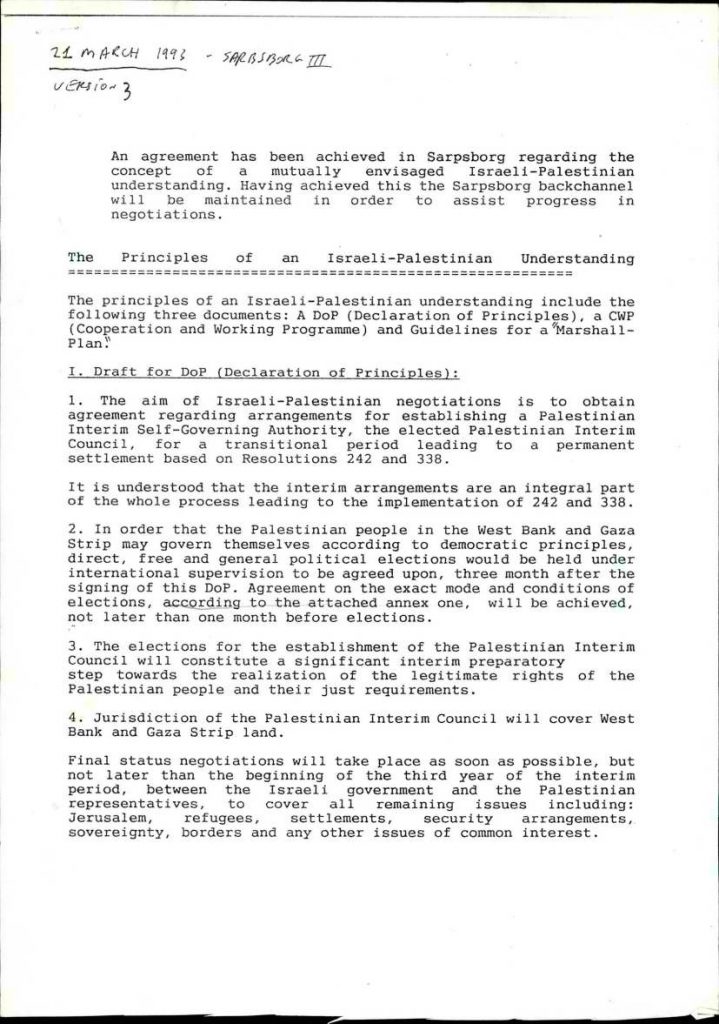

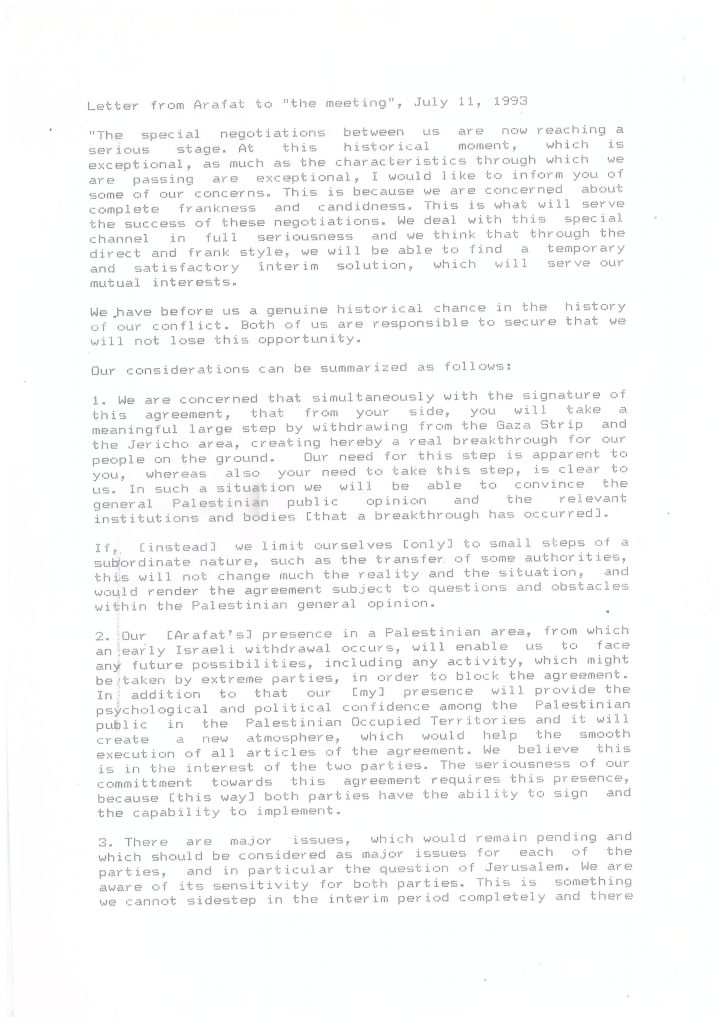

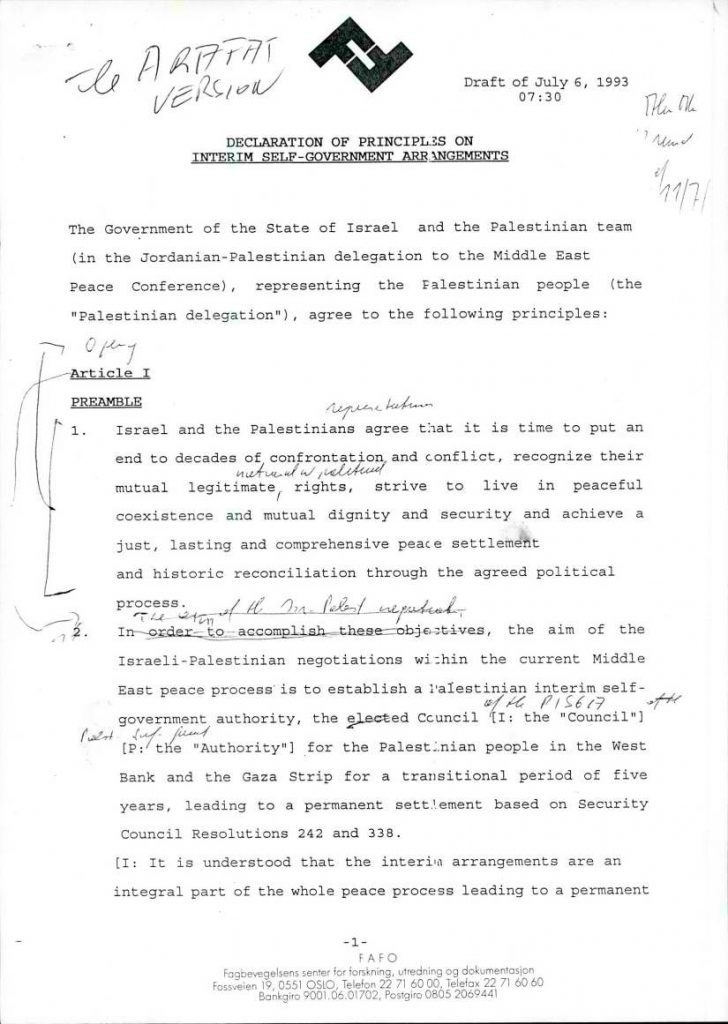

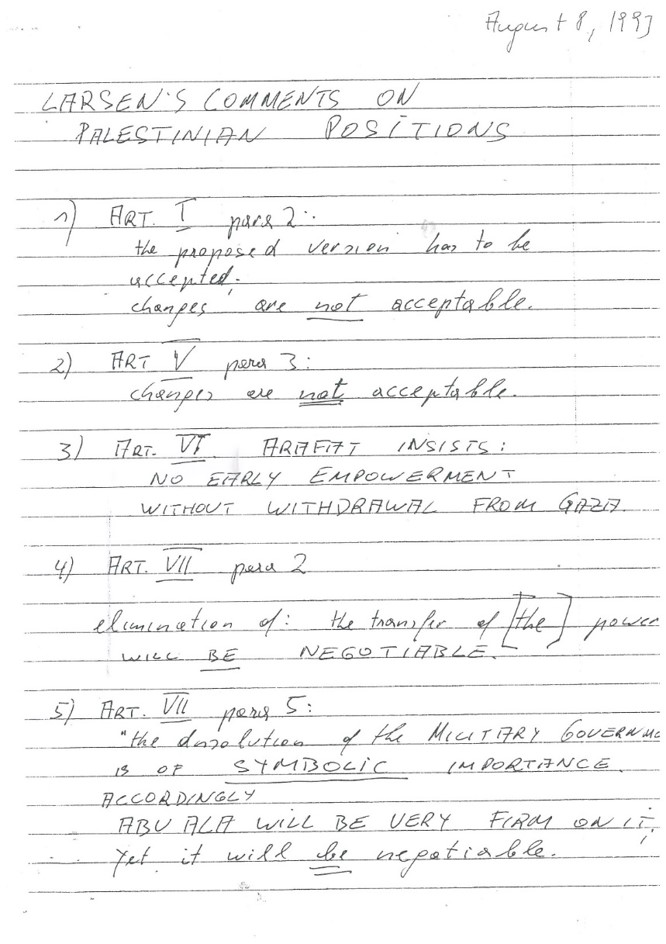

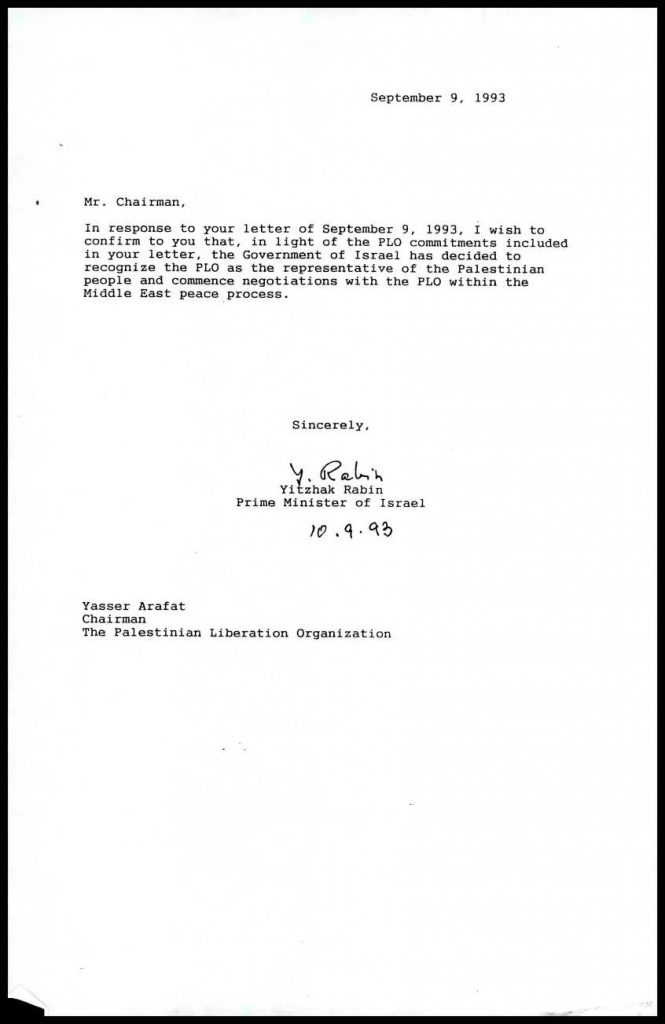

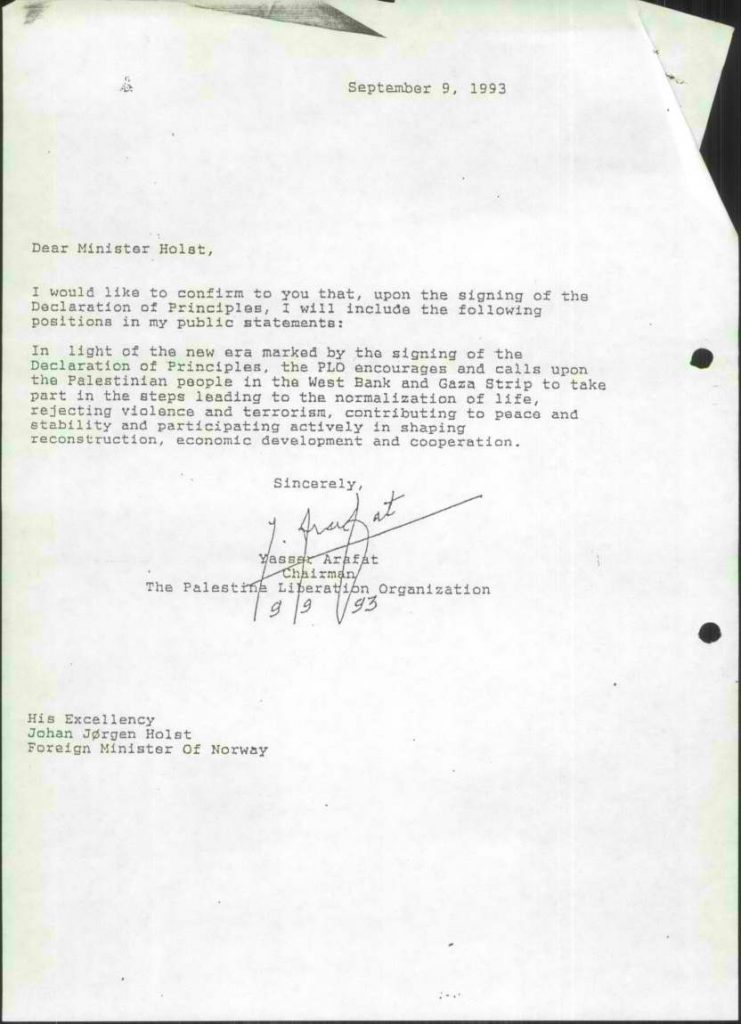

These talks were at first unofficial ones, and even after official representatives joined them in May 1993, they remained secret and so far no record of them has been found in the government files at the Israel State Archives. However, the Archives recently received a collection of documents on the “Oslo Process” from Dr. Hirschfeld, along with many additional documents on the activities of the ECF. It is now possible for the first time to get a first-hand picture of the negotiations in Norway and the path to the Declaration of Principles on an interim agreement and to mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO. The process was preceded by talks between Hirschfeld and Beilin and Palestinian leaders in the West Bank and Gaza, which began in 1989 following the first Intifada. The leaders were Faisal Husseini and Hanan Ashrawi, who became members of the Palestinian delegation to the Washington talks. They were affiliated with the PLO but not official members of the organization. Among other meetings, in 1989 “proximity talks” between Palestinians and Israelis, including Hirschfeld and Beilin, were held in The Hague, the capital of the Netherlands, which also served as a prelude to the Oslo process. These meetings, along with contacts with pro-Jordanian residents of the territories, are documented in the Hirschfeld collection

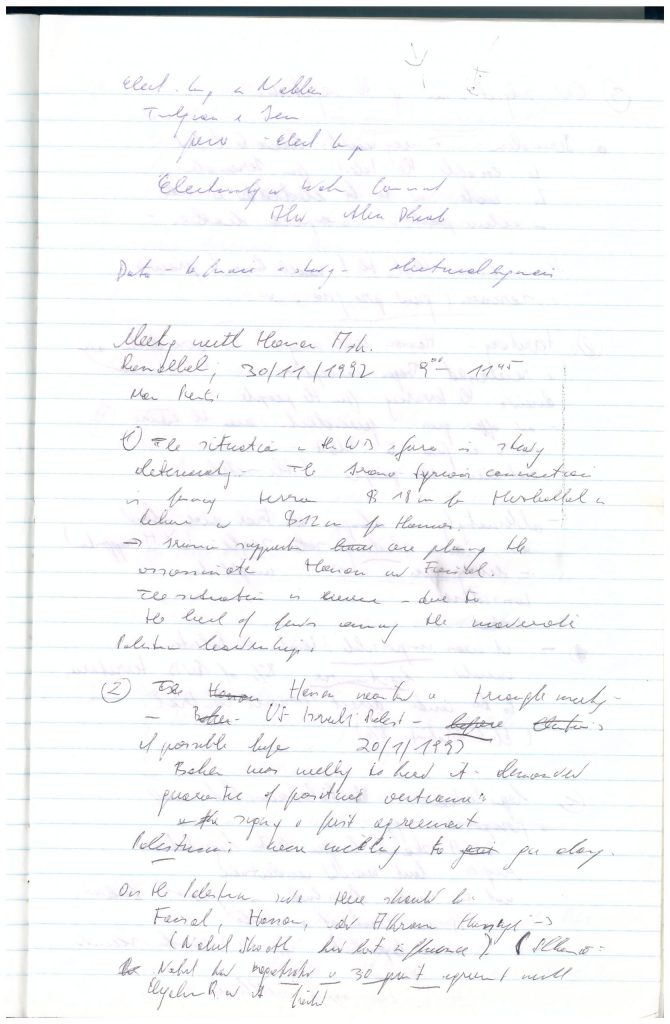

In this chapter we present a selection of unpublished sources from the collection. The files on the Oslo Agreement have been scanned and appear on the ISA website (mainly in Boxes P 5513, P 5514). They include minutes of the meetings, drafts of the agreement, reports to Prime Minister Rabin and Foreign Minister Peres and records of internal meetings of the Israeli negotiators. High-level talks in which Prime Minister Rabin took part are not included in the collection, and on this subject we have used secondary sources. Dr. Hirschfeld also gave the Archives a collection of “Appointment Diaries” including handwritten notes he made during the talks. Transcripts of some of them are in the scanned collection. With the kind help of Dr. Hirschfeld, we also deciphered and transcribed a conversation that was not previously printed, which appears in the selection given here.

One of the Hirschfeld diaries

For links to data on all the files in the collection uploaded to date, see here.