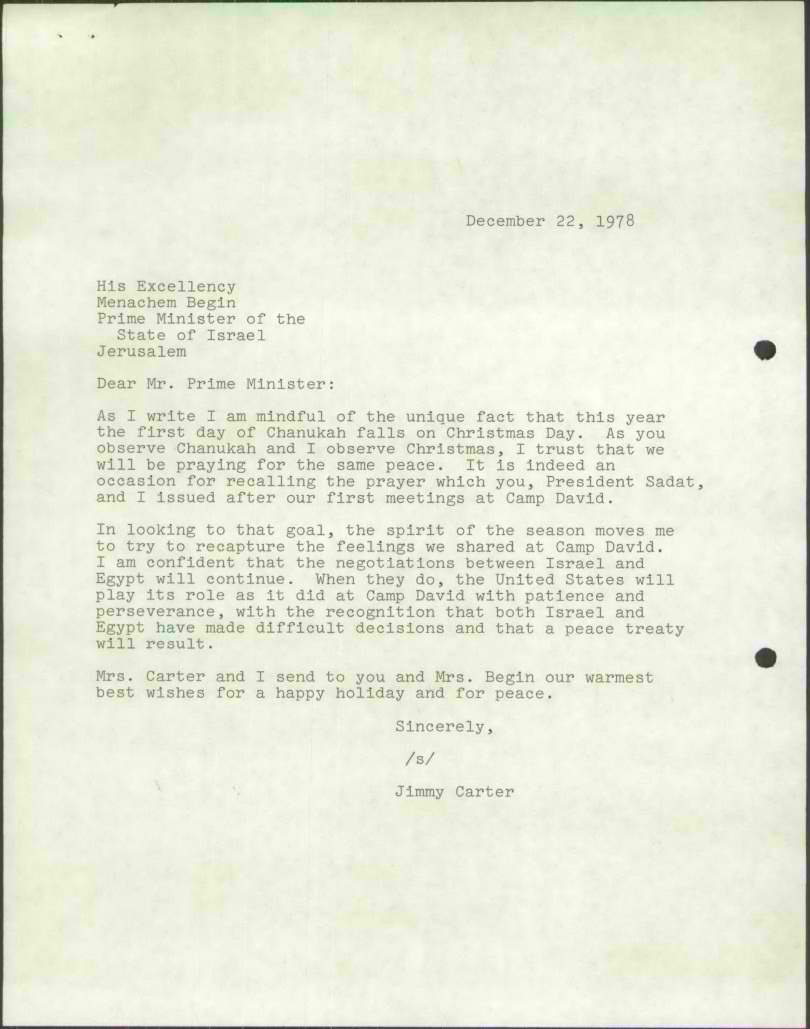

1. Buyer’s remorse? Problems in the peace talks

In mid-October talks between Israel and Egypt on an American draft peace treaty began in Washington. But soon the differences between the parties which had been papered over at Camp David began to emerge. The angry reaction of the Arab world forced Sadat to prove that he was still committed to the Palestinians and to an overall settlement. Begin, attacked by his friends and supporters for abandoning all of Sinai (see Document No. 41), was determined to make no more concessions. Carter too seemed to regret his decision at Camp David not to press Begin further on Palestinian rights. Ambassador Sam Lewis described their attitude as “buyer’s remorse.”‘

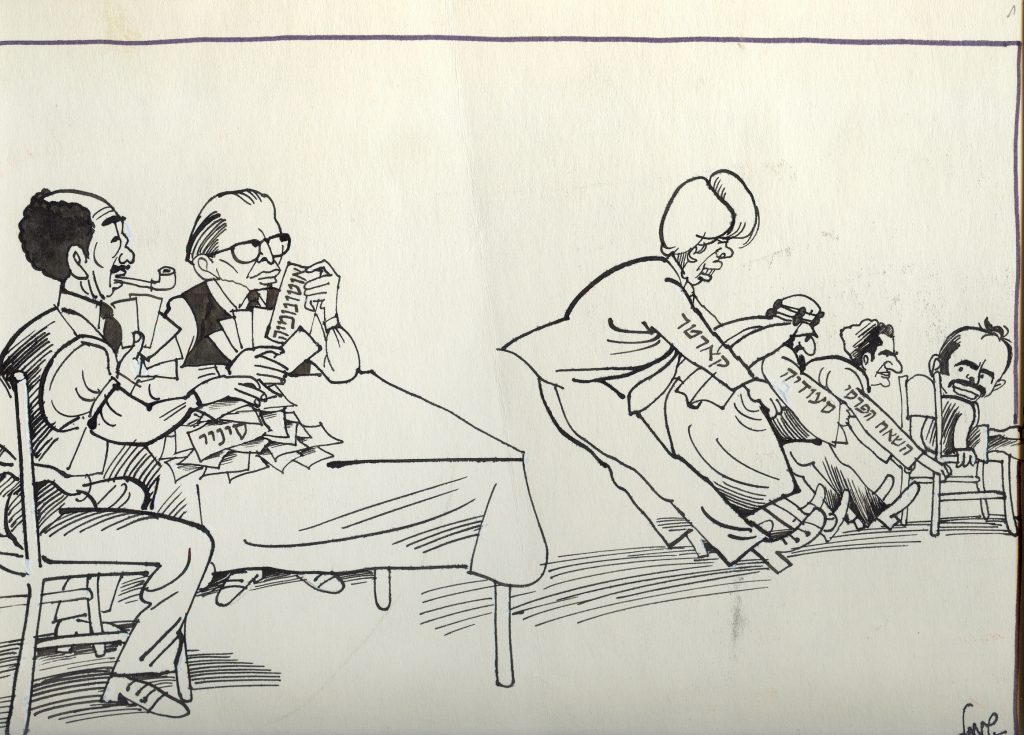

Carter was worried about the Jordanian and Saudi reactions to the Camp David Accords. The US had sent Vance to present them to the Arab states. His assistant, Alfred Atherton, reported to Begin that King Hussein was insulted that Jordanian cooperation was expected although he had not been invited to the summit. He was reluctant to commit himself unless full Israeli withdrawal was ensured. The Saudis wanted to support Sadat but were concerned about the reaction of the radical states, while Syria was firmly opposed. Atherton also met Palestinian representatives from the West Bank (see Document No. 42).

Carter, Saudi Arabia and the Shah of Iran try to drag Hussein to the negotiating table. Caricature by Shmuel Katz, courtesy of the Katz family

Carter propsed to open talks in Washington on the treaty with Egypt. Israel was in no hurry to conclude these talks, which would be followed by negotiations on the autonomy plan. In 1979 the run up to the Presidential campaign would begin and it would be harder to pressure Israel. Dayan, who was to head the delegation to Washington, held a consultation on 4 October with the other members, who included Weizman, Tamir and Rubinstein, and with senior Foreign Ministry staff. Barak was also there, although as a serving Supreme Court judge, it was not certain if he could go to Washington. They discussed the main issues of the treaty: stages of the withdrawal, what Egypt would give in return and what guarantees the US could provide. Dayan said that he hoped to postpone the opening of the autonomy talks (Document No. 43). The Egyptian delegation was headed by Boutros Ghali, now promoted to foreign minister, and Kamal Hassan Ali, the new defence minister (replacing Gamasy who had lost Sadat’s favour). Weizman and Dayan therefore led the Israeli team, but the government decided that they would represent the Ministerial Committee on Security, which would be responsible for the talks. Its members felt that the delegation at Camp David had given in to US and Egyptian pressure, and they kept Dayan and Weizman on a tight rein.

Unlike Begin, Carter wanted to conclude the treaty quickly (see Document No. 40). On 10 October he met with Dayan and Weizmann and urged them to speed up the talks so that they would end before the summit of Arab leaders due to meet in Baghdad at the end of October. They learned of a possible problem with the timing of establishment of diplomatic relations, which was not specified in the Camp David Accords. Carter said that Sadat refused to exchange ambassadors on the signing of the treaty, but would probably agree to do so shortly after the first stage of the withdrawal, to the El Arish-Ras Muhammad line. The exchange was important to demonstrate to the public that Israel was getting true peace. Dayan agreed to speed up the talks with the Egyptians but not to open talks on autonomy without the Jordanians or the Palestinians. (See Begin’s critical comments in Document No. 44).

On 12 October the talks opened at the White House, and then moved to Blair House, the official Presidential guest house. But as both delegations were staying on different floors at the Madison Hotel, they began to hold informal meetings there and it was even dubbed “Camp Madison”. Avraham Tamir and General Taha Magdoub quickly settled down to complete the work they had started many months earlier in the military committee, planning details of the withdrawal and arms limitations, and Zalman Enav, a Tel Aviv architect, was called in to draw up the lines and eventually prepared the maps for all sides.

A committee was also set up to prepare a draft treaty. But there difficulties soon arose. The Israelis feared that Egypt might get all or most of its territory back before the exchange of ambassadors, while Egypt wanted to link the exchange to the elections for a self-governing Palestinian authority. Israel refused to include in the treaty any reference to Judea and Samaria except a reference to the Camp David Accords in the preamble. In a meeting with Atherton and Assistant Secretary Saunders on 14th October, Dayan explained that the aim was to make it clear that the agreement with Egypt stood “on its own two feet” and there was no “linkage” between it and the agreements on Palestinian autonomy. Dayan also complained that the American proposed map of the first withdrawal would force Israel to evacuate a settlement (Neot Sinai) which was on the wrong side of the line. (Document No. 45). This mistake caused Carter considerable trouble, and in the end he had to ask Sadat himself to agree to change the line. To deal with Egyptian fears that Israel would not carry out the autonomy plan, Dayan proposed that Begin and Sadat exchange letters (or sign a joint letter) to accompany the treaty, committing them to hold negotiations on autonomy (See his telephone conversation with Begin, Document No. 45A). Dayan also repeated his request for Barak’s help, and after receiving permission from the President of the Court, Judge Sussman, Barak arrived in Washington.

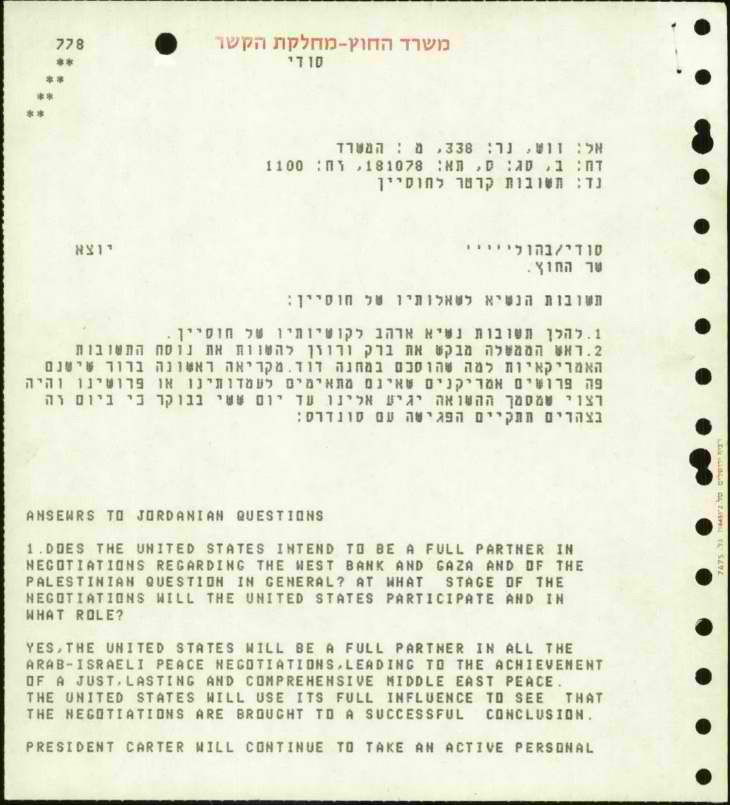

Relations between Begin and the Americans, already tense because of the argument over the settlement freeze (See Part 2), deteriorated further as a result of the US attempt to obtain Hussein’s support by supplying answers to a list of questions on the interpretation of the Accords.

First page of Begin’s letter to Dayan with the US reply, asking for a legal opinion. ISA, File A4314/2

Backed by the opinion of Barak and Meir Rosenne, Begin made a scathing analysis of the reply in a meeting with Assistant Secretary Saunders, claiming that it was contrary to Camp David and would encourage the Arab states to demand a Palestinian state and Sadat to adopt an extreme position. (Document No. 46).

On the same day, in Washington, Carter told the Israelis that he had demanded from the Egyptians to establish full diplomatic relations a month after the first withdrawal. He asked them to explain the article on Priority of obligations, (Article VI (5)) dealing with a possible clash between the peace treaty and other treaty obligations. Egypt did not want to say in public that the treaty counted for more than its obligations to other Arab states. Israel argued that without this clause Egypt could join a Syrian attack on Israel. After a long argument on linkage, Carter also agreed to Article VI (2) of the treaty, saying that the parties will carry out their obligations without reference to any other agreement. But the Israeli government and Sadat still had to agree to the draft. On 22 October Carter wrote to Begin appealing to him to recommend to the government to accept it and the exchange of letters on autonomy. (See Document No. 47).

The ministers returned to Jerusalem for a government meeting which lasted 17 hours over three days. The atmosphere was tense as a result of public reaction to Saunders’ meetings with West Bank leaders and his statements. The government approved the draft and the exchange of letters in principle, but Begin suggested some amendments. To gain the support of Sharon and Education Minister Zebulon Hammer, at Dayan’s suggestion the government also decided, despite the settlement freeze, to expand existing settlements, a decision which angered Carter and the Egyptians. At a meeting of Likud Knesset members Begin also announced that the Prime Minister’s Office would be moved to East Jerusalem. Although Sadat and Begin had just won the Nobel Peace prize, Carter warned that the success of the negotiations was in the balance.

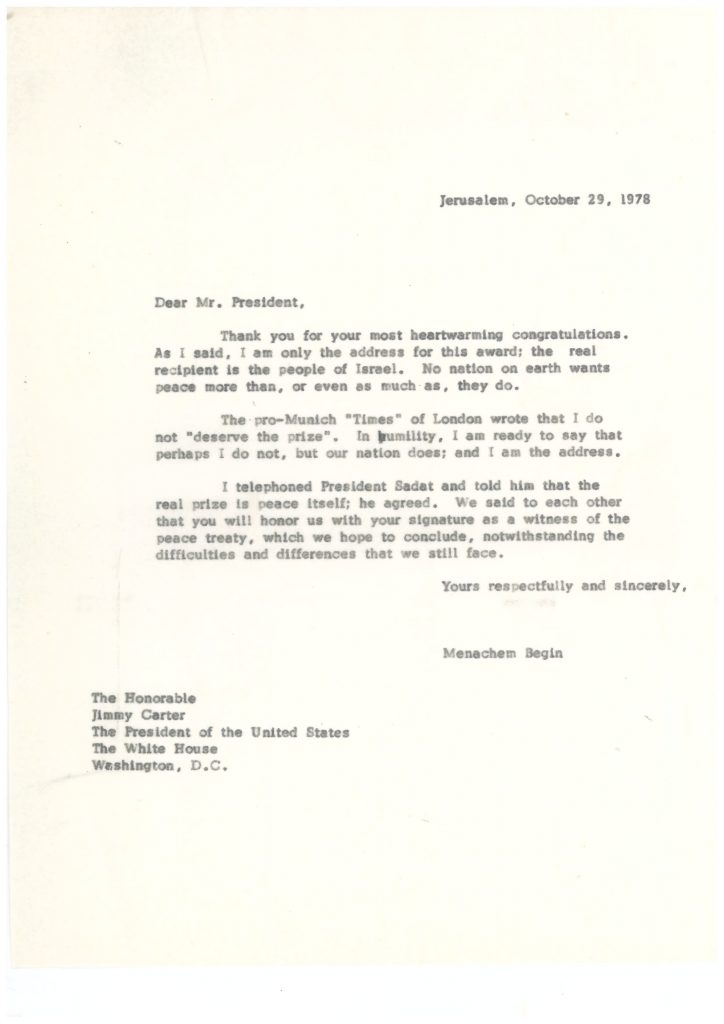

Begin’s reply to Carter’s letter congratulating him on winning the Nobel prize for peace, 29 October 1978. File A438/6

The Egyptians wanted to return to Cairo for consultations, but after Dayan threatened to leave, they resumed the talks. Dayan told Ghali and Ali bluntly that Israel had no intention of giving up its interests in the West Bank, “neither settlements nor Army [posts]”. (Document No. 48).

On 30 October Weizman wrote to Begin and asked him to ask the government to approve the early withdrawal from El Arish as promised to the Egyptians (Document No. 49). The government refused to change the date of 9 months as fixed in the Camp David agreements.

“Mr. Negotiations” on a stairway leading nowhere: a drawing found in the papers of the delegation to Washington

On 2 November Vance met with Begin, who was on his way to visit Canada, and the delegation in New York. Begin objected to setting a target date for the establishment of autonomy and to a clause in the preamble about Camp David starting with the word “Noting”. Vance warned him that without this clause, they would not have a treaty, and added angrily that any changes risked reopening issues that were settled (Document No. 50). Begin also brought up Israel’s request for economic aid to cover the costs of the treaty and asked to receive it as a loan from the US, instead of partially as a grant as arranged with Finance Minister Simcha Ehrlich. Vance refused to make any promises, and Carter objected strongly to the implication that Israel was trying to blackmail the US into giving aid.

The Baghdad summit condemned Egypt and threatened it with sanctions if the treaty with Israel was signed. Jordan and Saudi Arabia attended the summit and King Hussein, who was promised generous aid, met with his old enemy Yasser Arafat.

Under this pressure, Sadat and the Egyptian army reacted badly to the news that the Israeli government had refused to bring forward the withdrawal from El Arish (Weizman’s conversation with Ali, see Document No. 51). Weizmann told his friends that he had told Ali that as the negotiations wound down, everyone was becoming nervous and impatient: “You can have a long comfortable flight with a crash landing. I feel that we are going towards a bad landing“.

On 9 November Dayan met with Ghali, who had just returned from Cairo, and heard from him about the demand of Sadat and the Egyptian leaders to fix a target date for the elections on autonomy in 4-5 months and a date for Israeli withdrawal in order to show that Egypt would not sign a separate peace. Dayan and Weizmann were willing to consider some gestures to the Palestinians but rejected a new Egyptian proposal for autonomy in Gaza first. Now that it was clear that Jordan would not co-operate, Egypt proposed to implement autonomy in Gaza, where it had more influence, and to give it a special role there. Ghali suggested a solution to Israel’s concern about its oil supply after withdrawal from the oilfields in Sinai – extension of the US guarantee of 1975. (Document No. 52). Israel wanted a long term Egyptian commitment to sell oil to Israel, while Egypt saw inclusion of special treatment for Israel in the treaty as an infringement of its sovereignty. At this stage Vance turned down the idea, but four months later it was to provide a way out allowing the signing of the treaty.

The fears of both delegations of a breakdown in the talks were soon realized. The Israeli delegation, with the addition of Energy Minister Yitzhak Modai, flew to Toronto to meet with Begin before his decisive meeting with Vance, and told him about the new Egyptian demands. Barak and Rosenne emphasized that the treaty was nearly finished and it was very favourable to Israel. Weizman said that if the talks were stopped it would be hard to restart them. However Begin focused on what he saw as US and Egypt attempts to undermine the Camp David agreements, and the refusal of the Administration to discuss economic aid. He wanted to hold a government meeting immediately but Weizman and Dayan persuaded him to wait while they held further talks with the US. (Document No. 53)

The Administration was worried about their own relations with the Saudis if Sadat did not obtain their support. The Saudis were pressing Sadat to hold up signature on the treaty in order to obtain Israeli withdrawal and Palestinian self-determination, out of fear of attacks by radical states, such as Iraq and Libya, on their own regime. But the Americans themselves were in two minds how far to support Sadat’s new demands: they did not want to push Israel too far and endanger the treaty, when it was possible that neither Jordan or the Palestinians would cooperate in setting up autonomy anyway. After their experience at Camp David they realized that Sadat’s commitment to the Palestinians was limited and his main concern was the reaction of the Arab world, especially the Saudis. They decided to concentrate on a target date for autonomy, but rejected his ideas about Gaza. On 11 November Carter wrote a personal letter to Begin urging him to accept the draft treaty (Document No 54) and on the next day he spoke to him in Toronto, where Begin was the guest of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, and warned that the talks were on the verge of failure (Document No 55).

But internal pressure on Begin to make no further concessions was also strong, as we can see from a message from Arye Naor, the Cabinet secretary (Document. No. 56) telling Begin that the interior minister, Yosef Burg had said that he felt that the Egyptians and Americans were treating Israel as a defeated nation.

That day Vance met Begin and the Israeli delegation at Kennedy Airport in New York on Begin’s way back to Israel. The night before, Dayan, Barak and Rosenne met Vance and his team at the State Department for a final effort to reach compromise on the outstanding issues. Vance said that history would not forgive them if they failed, and Barak agreed. Dayan proposed to set a new target date for autonomy – by the end of 1979, after the first withdrawal by Israel but close to the nine months proposed by the US. A draft letter, this time from Carter to Sadat and Begin, was drawn up. Dayan promised to try again to persuade the ministers to agree to advance the first withdrawal in Sinai and said that any US commitment on aid to Israel could help. But at the meeting with Begin, Vance refused to commit himself on aid. Dayan was neutralized by Begin, who accused Vance of trying to take control of the Israeli delegation and refused to discuss the new draft of the letter on autonomy. (Document No. 57).

Begin and Dayan returned to Israel, while Weizman stayed in Washington to try and mend fences with Carter and the Egyptians. He met with Sadat’s deputy, Hosni Mubarak, and with Carter, and reported that Carter was liable to blame Israel if the draft treaty was not approved. On the other hand there were signs of a softening in the Administration’s stand on economic aid (See Weizmann’s report to the Knesset Defence amd Foreign Affairs Committee, Document. No. 59A).

On 19 November the government began to discuss the draft treaty, on a background of new Egyptian demands brought by Mubarak, and press reports that Egypt was trying to regain control of the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile opposition to Camp David in the West Bank was rising. Carter complained to the White House press corps on 16 November that the tension and mutual suspicion between Israel and Egypt, which had been dispelled at Camp David, seemed to have returned. Nevertheless Begin called on the ministers to adopt the draft treaty, if Egypt would also do so, and even agreed to drop his opposition to the “Noting” clause and to accept a legal formula on the status of Gaza. That evening Begin was greeted at a meeting of the Herut Central committee by an angry demonstration. After he threatened to resign, his policy was approved by 306 votes to 51. (See Document No 59). On 20 November Weizman presented his stand to a meeting of the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defence Committee and emphasized that Israel was making the agreement from a position of strength, and was not being forced into concessions as presented by the press – and some in the government itself. “We must be very careful not to give the impression that we signed [the Camp David agreements] and now we are going back on our word” (See Doc. No. 59A)

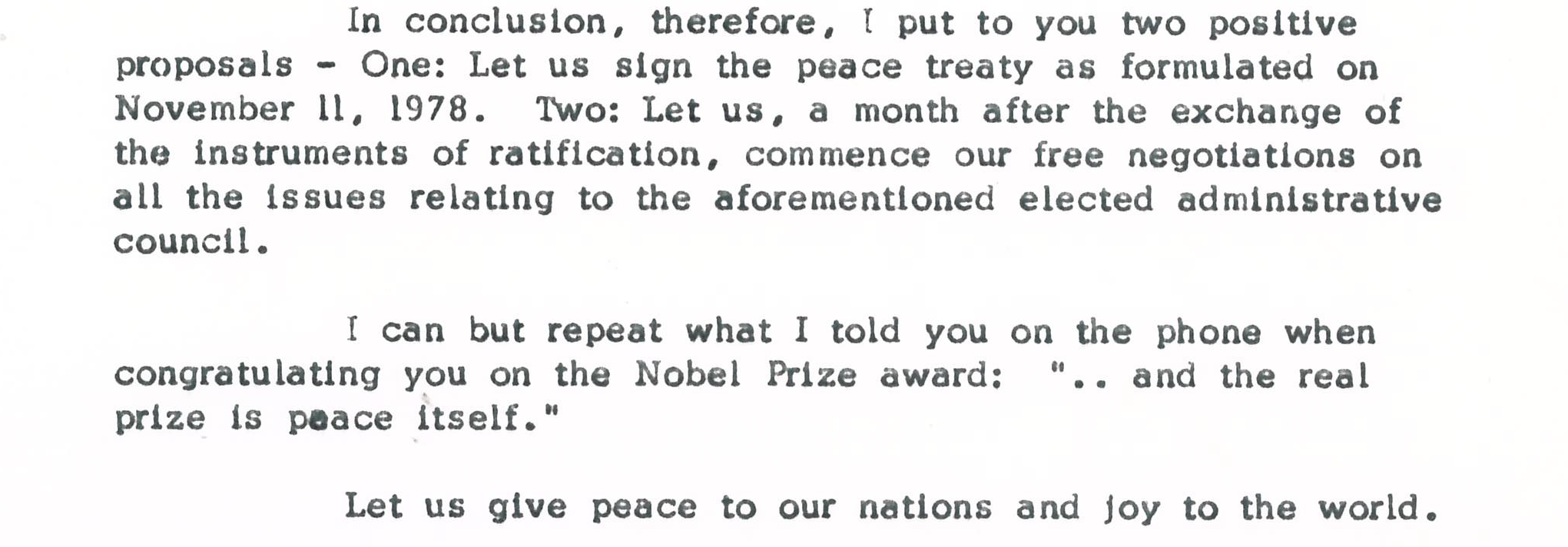

On November 21 the government approved the final version of the treaty by a majority of 15 to 2. According to the press, Hammer and Haim Landau of Herut voted against the proposal. The ministers unanimously rejected a target date for autonomy. Begin explained the decision to Carter in a telephone conversation (Doc. No. 61). Although Carter asked Begin to send Dayan and Weizman back to Washington for more talks, in fact the government decision marked a stalemate in the negotiations. Against a background of warlike press statements on both sides, Begin and Sadat exchanged long argumentative letters. In his letter sent on 30 November (Doc. No. 62) Sadat listed all the advantages that peace offered Israel and accused Israel of frittering away time on minor points and going back on points it had already accepted, including bringing forward the interim withdrawal.. If autonomy could not be set up due to the Palestinians. Israel would not be held responsible. It was not doing enough to encourage moderate Palestinians. On 4 December Begin replied pointing out that Egypt too insisted on legal formulas where its interests were involved.

Extract from Begin’s reply to Sadat, ISA, File A4156/1

But there was no real dialogue between them.