Introduction

On 26 March 1979 Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat signed a peace treaty between their two nations. Afterwards they joined hands with US President Jimmy Carter in the famous triple handshake, symbolizing an event which changed the history of the Middle East. The ceremony on the White House lawn barely hinted at the dramas of the previous months. The negotiations overcame many obstacles before they reached their goal. Frequently it seemed that they would fail, and the area would return to the era of conflict and bloodshed its inhabitants knew so well.

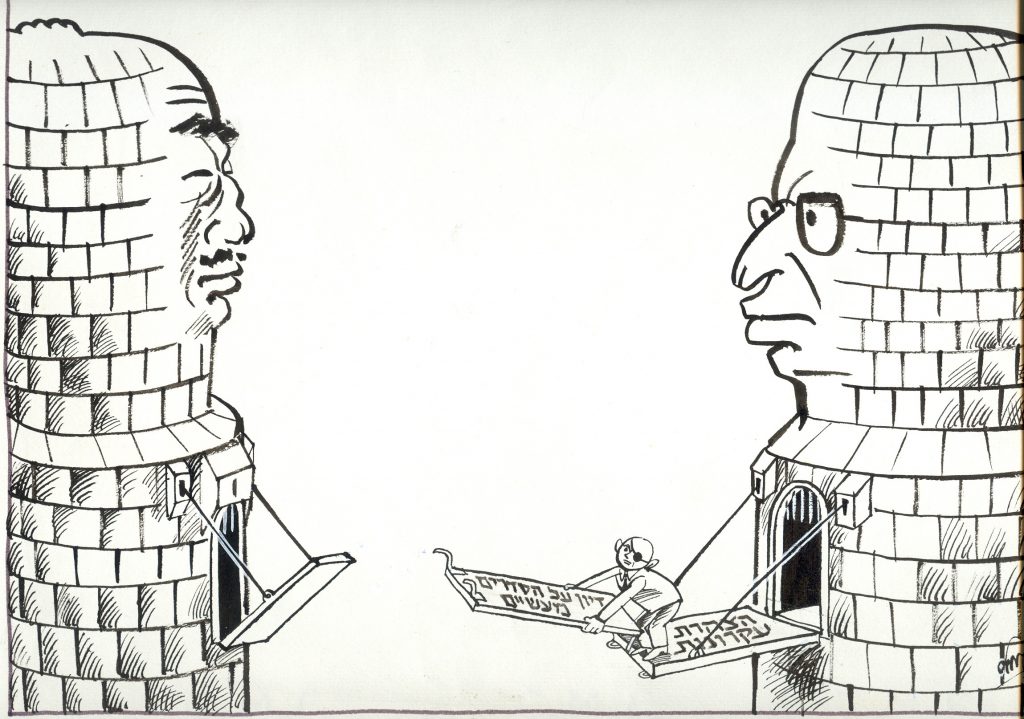

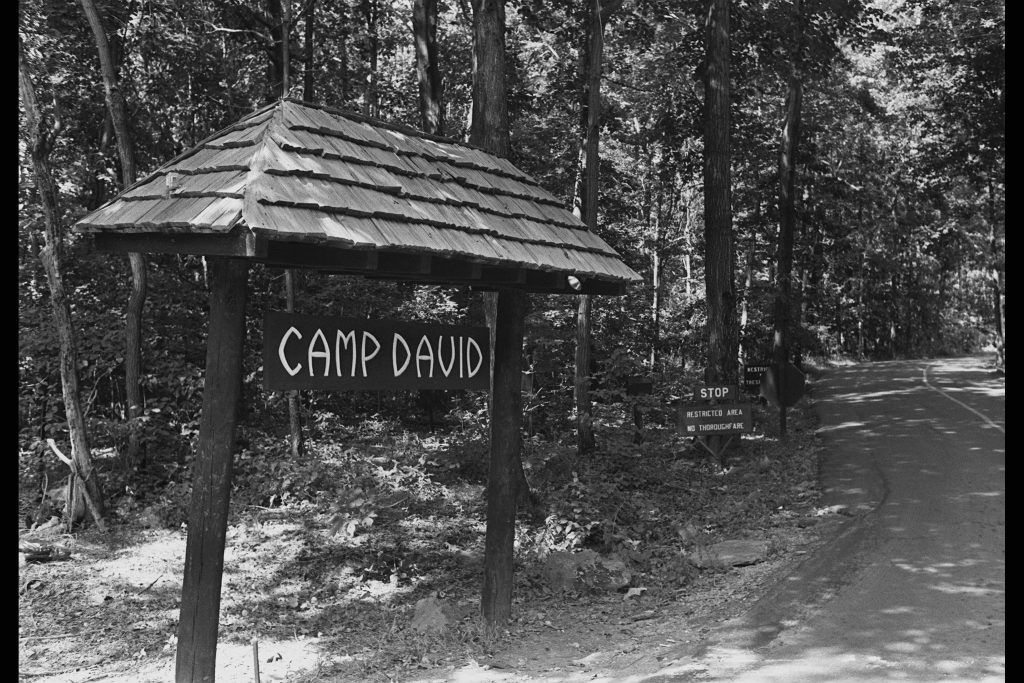

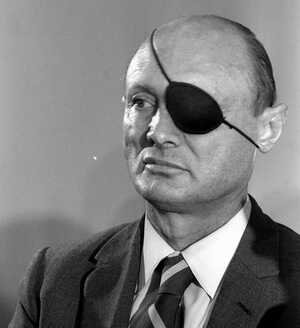

Only nine months earlier, in the summer of 1978, the parties had reached deadlock. The Israeli government, plagued by internal dissension, had clashed with the US administration, which blamed Israel’s obstinacy for the lack of progress. The high hopes raised by President Sadat’s visit to Israel had dissipated. Months of talks, at times direct and at others with US mediation, failed to bring a breakthrough. Each side barricaded itself in its positions and condemned the other. In July 1978 an attempt was made to renew the talks, but Sadat, offended by Begin’s public rejection of his request for an Israeli goodwill gesture, again broke them off. President Carter invited Begin and Sadat to a summit conference in his mountain retreat at Camp David. There agreement was reached on a framework for peace, which eventually led to the ceremony in Washington.

However the process of turning the framework into a binding peace treaty, which began in October 1978 in Washington and was supposed to take three months, soon ran into difficulties. Once Begin and Sadat returned from the summit, where they were isolated from outside pressures, the disagreements between the two countries re-emerged. Egypt wanted to link the bilateral agreement with progess on Palestinian autonomy, while Israel rejected this linkage. Saudi Arabia and Jordan refused to support the agreement and US attempts to draw them in led to further complications. Although the Israeli government approved a draft treaty on 21 November 1978, the talks again broke down. After several unsuccessful attempts, they were restarted in February 1979 after the revolution in Iran. It took athe personal intervention of President Carter, and a dramatic visit to the Middle East to bring about the final breakthrough.

PM Begin speaking at the peace signng ceremony, 26 March 1979. GPO

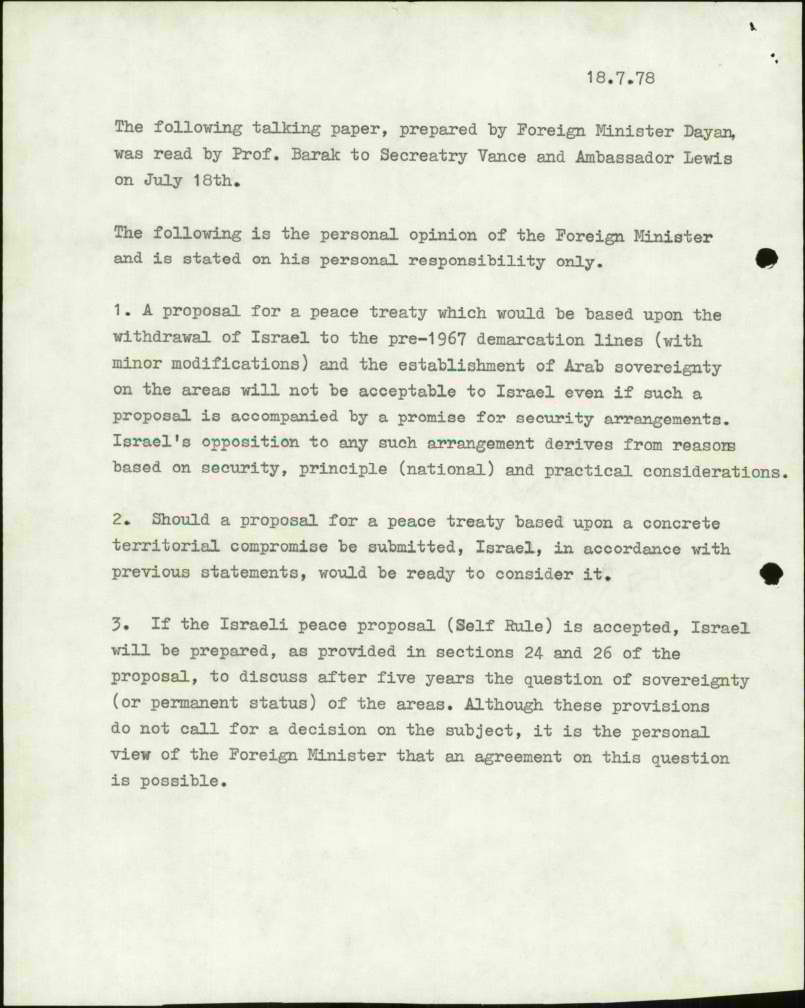

To mark the 40th anniversary of the Camp David summit and the signing of the peace treaty on 26 March 1979 we present a special publication of 93 documents, 27 of them in English, including telegrams and letters, records of conversations and meetings, and records of government meetings. They include documents first published in 2013 and 37 new documents on the later stages of the negotiations. We also present a collection of 46 scanned files on Camp David and the negotiations on the peace treaty and 7 stenographic records from the Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defence Committtee, released for the first time for publication by the military censorship. Part 1 opens with documents on the failed attempts to bridge the gap between the two sides in the summer of 1978. Part 2 deals with the doubts and dramas at Camp David until the final success. Among the documents are five records of the meetings with the US delegation recorded by the legal adviser Prof. Aharon Barak in his own hand, presented here after transcription with the kind assistance of Prof. Barak. We also present a selection of the internal consultations of the Israeli delegation. The rest were used for preparing the introductions.

Part 3 show hows, despite the Camp David accords and areas of agreement between Egypt and Israel, negotiations broke down again, due to opposition in the Arab world and among Begin’s previous supporters. Part 4 deals with the intervention by President Carter, the second Camp David conference, Begin’s visit to Washington and Carter’s decision to go to the Middle East. His dramatic last minute visit to Cairo and Jerusalem in March 1979 opened the way for the signing of the treaty.

See all the new documents in the special publication on our Hebrew website

See “Making peace”, our previous publication in Hebrew

Some documents from the ISA in English translation, together with some of the US documents on the peace process, can been seen on the website of the Center for Israel Education.

See also the historical documents in English on the website of the Israel Foreign Ministry and the Carter Library exhibit on the Camp David Accords.