ג.1 | The discussions before Kissinger's return: the importance of American aid

After the head of Syrian intelligence, General Shihabi, visited Washington, the Israeli embassy reported that the Syrians had rejected Dayan’s proposal, but agreed for the first time to a demilitarized zone and limitation of forces. Kissinger commented that he would only come if Golda Meir and Dayan told him it was worthwhile (see Gazit’s reply, Document 20, MFA 6857/10). In the meantime, discussions with the Americans continued on the terms of military aid.

At the same time, the war of attrition intensified, in particular around the Mount Hermon outpost. On April 14, it was again captured by the IDF. Syrian commando forces tried to recapture it but were repulsed. Two Israeli planes and several Syrian planes were shot down in air battles. On April 27, the Syrians shelled another post and caused casualties. A helicopter coming to evacuate them hit the side of the mountain and six of the crew were killed. The Syrians shelled the Hermon outposts every day, and the IDF responded with air strikes on the Syrian army camps on the slopes of the mountain. On the night of May 1-2 two soldiers were killed in an attack on a tank unit and two more were captured. The losses increased public hostility towards Syria and made it difficult for the government to make concessions.

The Mt. Hermon outpost recaptured in October 1973. GPO.

On April 11, members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine from Lebanon carried out a massacre in Kiryat Shmona, in which 16 civilians and two soldiers were killed. Israel responded with an air strike in Lebanon, and the United States rejected its request to veto a condemnation resolution in the UN Security Council, and even joined in the condemnation. According to press reports, Kissinger justified the vote due to Arab pressure and his desire to ensure the success of his mission to end the war and achieve the agreement with Syria. (For Dinitz’ protest, see Document 21, A 7033/11).

On April 29, a consultation was held in preparation for his arrival (Document 22, A 7073/17). After Golda Meir and Mossad head Zvi Zamir presented Kissinger’s well-worn geopolitical arguments, Dayan said that it was time for long-term thinking, especially about the next phase of negotiations with Egypt. The actions of the Americans were not unreasonable and they would provide economic and military aid to the Arab states. If Israel was not integrated in this plan, it would not prevent the Americans from advancing. Dayan proposed negotiations with them that would guarantee Israel “arms and grants to buy them and political help on issues important to Israel” – such as deterring the Russians and securing oil sources. In his opinion, they might also be able to obtain a letter from President Nixon, declaring that he considers the withdrawal in the Golan to an agreed line a final one, and that he will not demand another withdrawal. Dayan added that the Purple Line was not sacred. He thought that the eastern neighbourhoods of Quneitra could be given up – about a third of the city

Most of the ministers supported Dayan’s position. Sapir spoke of the high economic and human cost of continuing the war. Peres doubted the chances of success of Kissinger’s plan to drive the Soviets out of the region, but he too thought that the IDF was having trouble meeting its aims, including maintaining the latest weapons. Israel needed a cease-fire and a respite.

Allon argued that the debate about Quneitra was theoretical, because Kissinger had already promised it to the Syrians. If they gave up the Quneitra Valley, they were actually giving up the land of the three kibbutzim. In his opinion, the Americans had committed themselves to the Arabs to return Israel to the 1967 borders in stages. He was concerned about Kissinger’s need for achievements at any cost, against the background of the Watergate affair and Nixon’s desire to make a state visit to the Middle East. Golda Meir repeated her concern about the atmosphere in the army and in the public. Dayan said that he was not ready to move the military line west in Quneitra, even if this led to war, or to give up the kibbutz land.

At the government meeting on April 30, Dayan’s position on American aid was supported by Dinitz, who arrived from Washington, and the foreign minister. Dinitz described the struggle in Congress to approve financial aid to Israel according to the president’s decision. He warned that the Americans had not yet decided how much Israel would receive in 1975, which hinted at pressure on Israel to cooperate. Dayan repeated his views on the importance of relations with Egypt and the need for US arms and money to pay for them. Israel had ordered arms for a decade, which would cost 4 billion dollars, and for which it could not afford to pay.

His position was supported by the new Chief of Staff, “Motta” Gur, who was appointed on April 14. Gur had previously served twice as the head of the Northern Command. He had also served as the IDF attaché in Washington and participated in the military talks with the Egyptians in Geneva after the conference. Gur believed that negotiations should be conducted from a position of strength, but that the Syrians were realistic and they too had an interest in a period of calm.

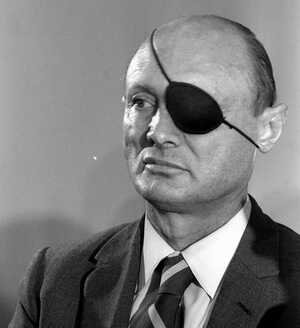

Lieutenant -General Mordechai “Motta” Gur, the Chief of the General Staff. Photograph: GPO

At the meeting (Document 23), he warned that if there was no agreement, serious fighting would develop, either initiated by Syria or as a preemptive strike by Israel. Intelligence suggested that Egypt and Jordan would join in. Israel’s dependence on arms and aircraft from the US must be weighed against the need for territory and whether that territory was critical to Israel. Gur did emphasize the importance of controlling the Hermon outposts for electronic warfare and the advantages of the Purple Line, However, Quneitra and the village of Rafid had no military importance, “and if I, as Chief of Staff, have to answer the question of a better relationship with the United States and the continued supply of weapons as against Quneitra and Rafid – my answer is unequivocal and clear.” There was no danger allowing Syrian civilians into Quneitra and in his opinion the Syrians only needed the eastern parts of the city.

Eventually it was decided to present to Kissinger both the map Dayan had brought to Washington and the new map, without the proposal to evacuate eastern Quneitra. The negotiating team could discuss this with him on condition that they clarifed a number of “essential matters”: preserving the settlements, arms supply and financing, Egypt’s commitment not to join Syria if a war breaks out, guaranteeing fuel needs, negotiating another stage with Egypt and the fate of the small community of Syrian Jews (Israel sought to use the opportunity to allow them to leave). This meeting established the outlines of the Separation of Forces Agreement from Israel’s point of view.

Before the arrival of Kissinger, who was coming from Cairo, the negative publicity about him in the Israeli press increased. “Maariv” reported that Begin had cut short his visit to the US in order to head a campaign against withdrawal beyond the Purple Line. An advertisement by a group called “Citizens for the Prevention of a Political Holocaust” called for action against the government’s capitulation to the “High Commissioner” (Kissinger). The editorial also opposed withdrawal to satisfy the “Syrian lust for prestige”, in view of the American condemnation of Israeli action in Lebanon.

Demonstrations against the UN vote by the Americans after the attack on Kiryat Shmona near the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where Kissinger was staying, 2 May 1974. Photograph: Ya’acov Saar, GPO.

The heads of the US Administration were kept informed about the atmosphere in Israel by their embassy in Tel Aviv. Kissinger and Nixon himself wrote personal letters to Golda Meir, in which they tried to justify the vote at the UN. Kissinger wrote that the US had condemned the attack in Kiryat Shmona in another statement. The president emphasized the importance of the secretary’s efforts to weaken Soviet influence in the region and mentioned the generous aid Israel had received during and since the war (Document 24).