ב.1 | Formulating a Proposal – and Forming a Government

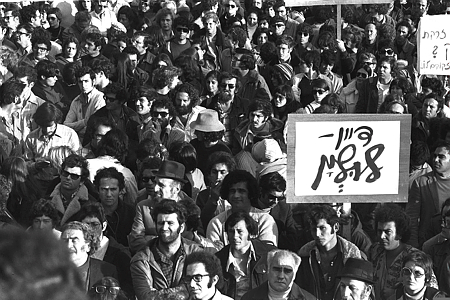

As the talks with Syria were about to open, Prime Minister Meir was still trying to form a coalition in the face of many difficulties. Within the Labour party, there were divisions between the “doves” and Dayan and his Rafi faction, who supported a national unity government with the Likud. The insistence of prominent rabbis that the National Religious Party should demand amendment of the Law of Return (the “who is a Jew” issue) before joining the government was also causing difficulties. At the same time a popular movement was forming against the government, many of its members reservists demobilized after the agreement with Egypt. At the beginning of February, reserve captain Motti Ashkenazi began a hunger strike in front of the Prime Minister’s Office. He was quickly joined by other protesters, demanding Dayan’s resignation. Dayan, who felt the party was not supporting him, threatened that Rafi would stay out of the coalition.

Motti Ashkenazi, leader of the demonstrations against the government, February 1974. Copyright © IPPA . Dan Hadani Collection, The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, The National Library of Israel

Another popular movement, Gush Emunim, was founded at the same time. Its leaders saw increased settlement in Judea and Samaria as the proper response to the war and the mood of national depression. They were afraid that withdrawal in the Golan Heights would be a precedent for Judea and Samaria, and would play an important role in the opposition to withdrawal. Many of their leaders were ex-students at Merkaz Harav, the yeshiva of Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook.

On February 24, before Kissinger’s arrival with the list of POWs, a first government meeting was held on Israel’s withdrawal plan (Document 13). The Chief of Staff presented the IDF’s maximalist plan for withdrawal within the enclave, dividing it into a Syrian area, a buffer zone area held by the UN and an Israeli area, including the Hermon outposts. Syrian citizens would be able to return. It included a plan for limitation of forces, like those in the agreement with Egypt. Israel would demand that there would be no surface-to-air missiles at a distance of 30-40 kilometres. Police Minister Shlomo Hillel reminded his fellow ministers that Israel had already offered to allow residents of the enclave to return and to transfer the Hermon outposts captured in the war to the UN in exchange for the prisoners. It could not now offer less.

At this meeting, for the first time, concern for the fate of the Israeli settlements on the Golan Heights was expressed. Ministers Yosef Burg and Moshe Kol raised fears that the Syrians would violate the agreement and harass the settlements. Burg also warned against a public backlash, which would lead to demonstrations and petitions against withdrawal. Allon replied that he understood their doubts, but settlers who went to border areas accepted the risks. What they really needed was an agreement to stabilize the ceasefire. It was doubtful whether the Syrians would accept the IDF’s proposals. Dayan warned that the war with Syria could flare up again, and remaining on the current line would certainly lead to war. Golda Meir added that the Syrians would demand a withdrawal beyond the Purple Line (the line of October 6, 1973). But that fear did not justify inaction. She wanted to help the Americans to lift the oil embargo, and also to help Egypt. The Chief of Staff confirmed that the Syrians would submit an extreme demand for withdrawal, including territory beyond the Purple Line, and he defined the IDF’s proposal as “optimistic”.

On February 27, after he had given Golda Meir the list (Document 14, A 7068/9), Kissinger met with the negotiating team, which included the Prime Minister, Eban, Allon, Dayan, Dinitz, Elazar and others (See the record of the meeting in English, A 7068/9). He said that he did not justify the agreement with Syria on military grounds and its content was of no importance. It was the act of signing an agreement with a radical Arab country that was important, as well as encouraging the moderate Arab countries, including Egypt, and expelling the Soviets from the area. The ministers’ reasons for rejecting withdrawal beyond the Purple Line mainly referred to settlements. The prime minister said that since Israel did not lose territory in the war, unlike the Egyptian front, there was no basis for the Syrian demand for territory beyond the October 6 line. She also resented the fact that Assad did not observe the ceasefire and continued to attack settlements.

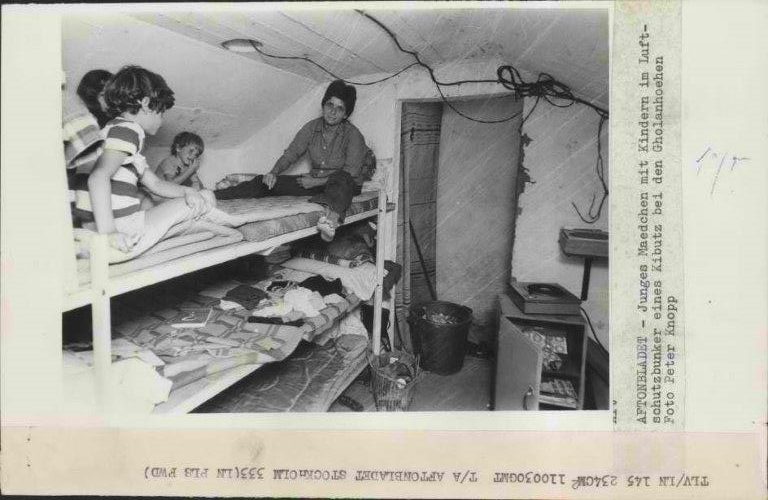

Women and children in a shelter in a kibbutz on the Golan Heights. ISA, Press photograph collection, TS 3009/199

After the proposed line was presented, Kissinger said that it was not serious and that he had no intention of presenting it to the Syrians. He suggested postponing the start of negotiations for ten days and sending an Israeli representative to Washington, with a Syrian one arriving later. He suggested that Dayan (or whoever replaced him if he did not join the government), should come to Washington. Already at this meeting, Kissinger accepted the principle that settlements should not be dismantled as part of a separation agreement. In his opinion, the line with Syria should not be brought closer to the Israeli one and it was better to expand the UN held area. Eban asked if there was no danger in handing over all of Israel’s assets in the Golan Heights at this stage. Kissinger replied (contrary to what he had promised the Syrians and the Saudis), that negotiations on another withdrawal could be postponed indefinitely.

After visiting Cairo, Kissinger returned to Israel and explained Sadat’s position: if Israel insists on withdrawing to the Purple Line and war breaks out, he will be forced to support Syria. But a withdrawal of a few kilometres more, perhaps from Quneitra, could solve the problem. Golda Meir replied that talking about withdrawing beyond the Purple Line was “dynamite in Israel”. Kissinger emphasized that Sadat was ready to help convince Assad to accept a proposal similar to the separation agreement with Egypt (Document 15, A 7069/8). In another meeting with Assad on March 1, Kissinger talked about the difficulty of changing Israel’s position. Assad presented Syria’s minimum demands – a withdrawal of about 8-10 kilometres, including Quneitra and the hills around it.

After visiting Saudi Arabia, Kissinger returned to Washington and did not stop off in Israel. At a summit of Arab countries, it was decided to end the oil boycott of the United States, but to re-evaluate the decision two months later – to ensure progress on the agreement with Syria.

At the government meeting on March 3, Warhaftig asked whether the separation agreement was more urgent for Syria or Israel. Could Israel risk renewing the war? In his opinion the aim should be a full peace agreement. Dayan explained that Israel was paying a high price for not having an agreement, including the continued mobilization of 20,000 reservists. Maybe, seen objectively, the situation put more pressure on the Syrians, he said, but in practice Assad did not care about the villagers who were driven from their homes. Israel was in dire need of American aid and “in my opinion, we are under a lot of pressure.” (Document 16, extracts from the meeting). The government decided to accept Kissinger’s request to send a representative to Washington.

At the same time, the war of attrition in the enclave was intensifying. The Syrians shelled the settlements on the Heights and IDF positions and began to build a new road to the outpost at the peak of Mount Hermon, abandoned by the IDF in the winter due to weather conditions. The war of attrition affected not only the talks with Kissinger but also the formation of the government, which had reached a crisis point. At a meeting of the Labour Party Bureau and the Alignment faction in the Knesset on March 3, after it was decided to set up a minority government based on the support of 58 Knesset members, attacks on the leadership were again heard from the left and threats not to vote for the list of ministers. Others warned that a minority government would not last long and said that a national unity government should be established. Golda Meir then announced that she would inform the president that she was giving up the attempt to form a government. She left the hall amid cries of “Golda, don’t go…” A delegation was chosen to appeal to her to return, which she did. But the infighting continued. Many attacked the idea of a unity government, due to the Likud’s opposition to the Geneva Conference and the agreement with Egypt, and the fear it would prevent an agreement with Syria.

After it was suggested that Yitzhak Rabin should replace Dayan as Minister of Defence, Dayan and his colleague Shimon Peres agreed to enter the government in light of reports of the danger of renewed fighting in the north. Some suspected these ministers and the government of exaggerating the danger of war for political purposes. On March 8, Galili said that some of the public was convinced that the news about tension in the north was intended to help form the coalition.

On March 10, Golda Meir presented the government in the Knesset. She spoke both of strengthening the IDF and refusal to return to the 1967 lines, and of the need to transform the cease-fire and separation of forces agreements into peace treaties. Begin ridiculed the government and Meir and Dayan personally for their lack of credibility, and for their use of information about the threat of war for political purposes. Nevertheless, the Knesset expressed confidence in the government by a majority of 62 to 46.

The new government with President Ephraim Katzir, 10 March 1974. Photograph: Moshe Milner, GPO