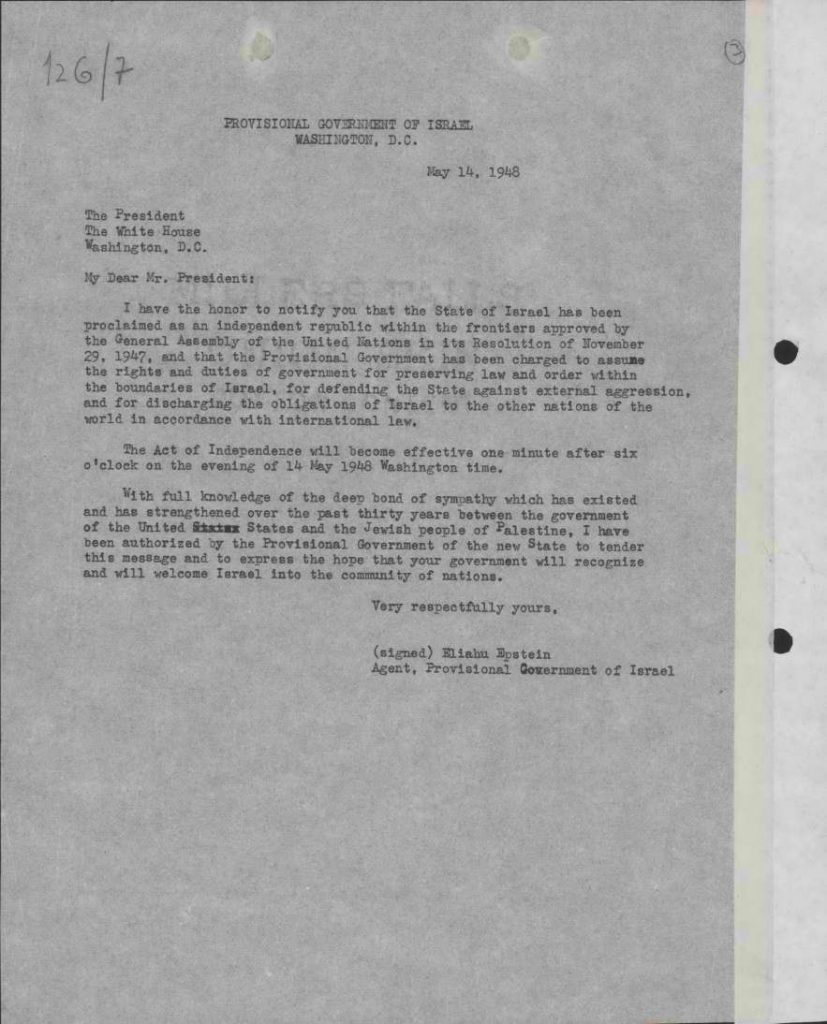

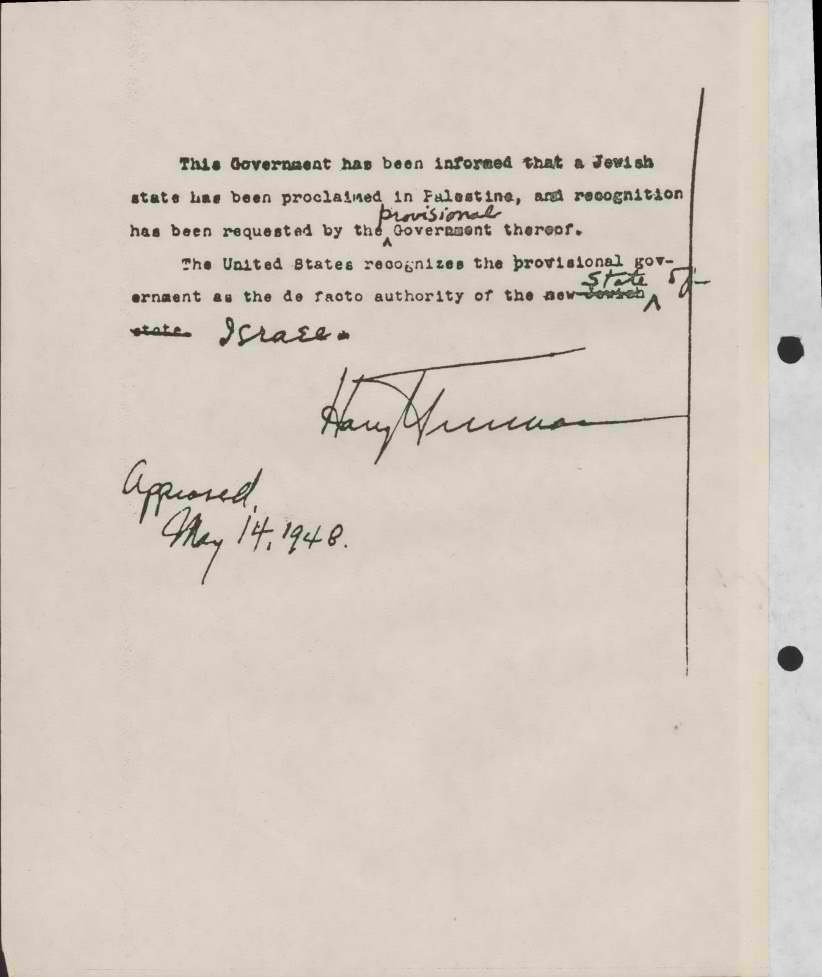

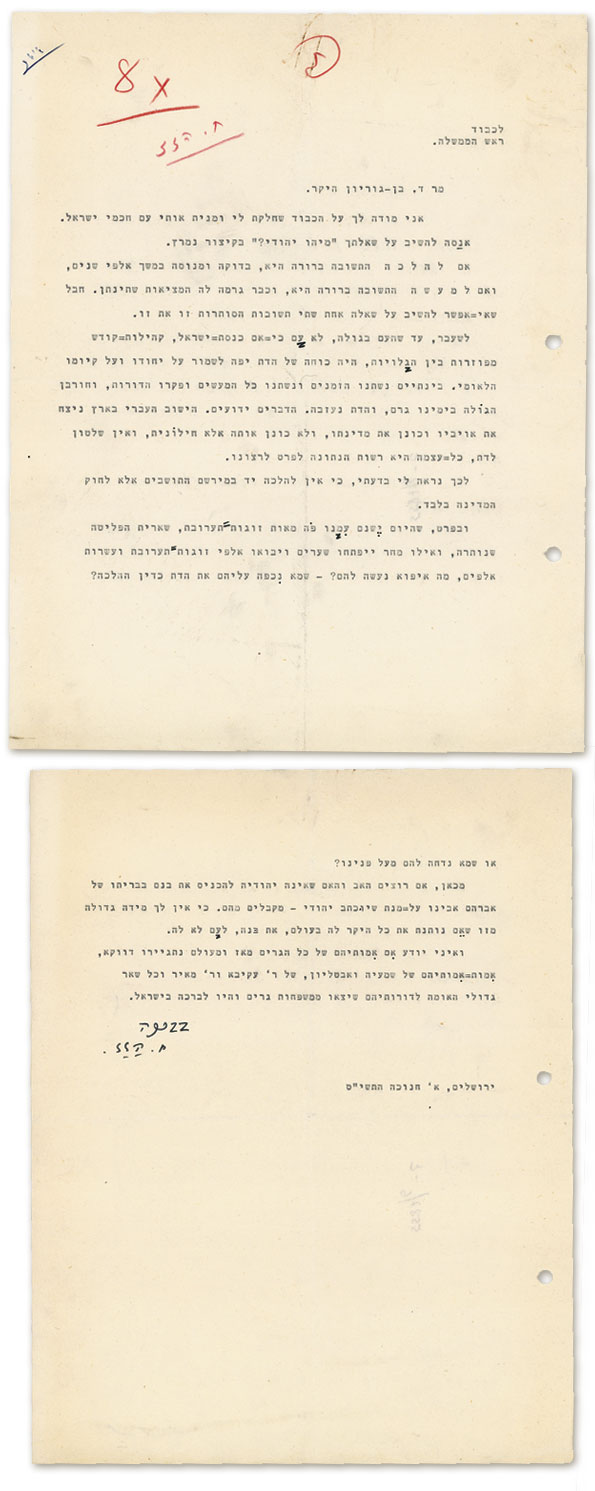

“…A Jewish State in the Land of Israel, the State of Israel…”

The name of the State

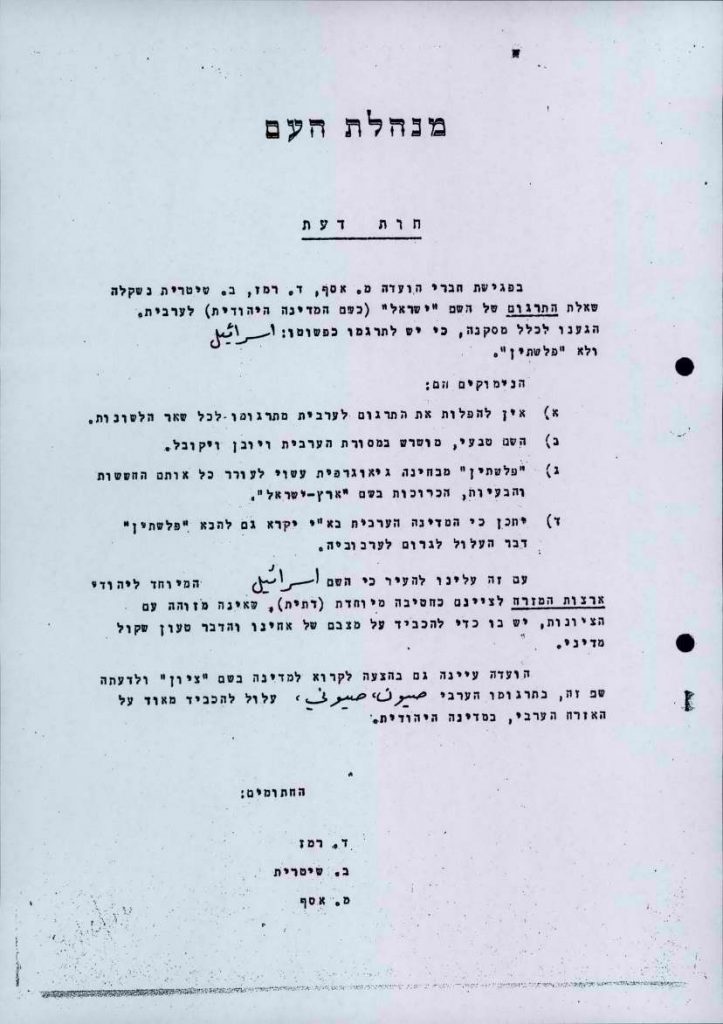

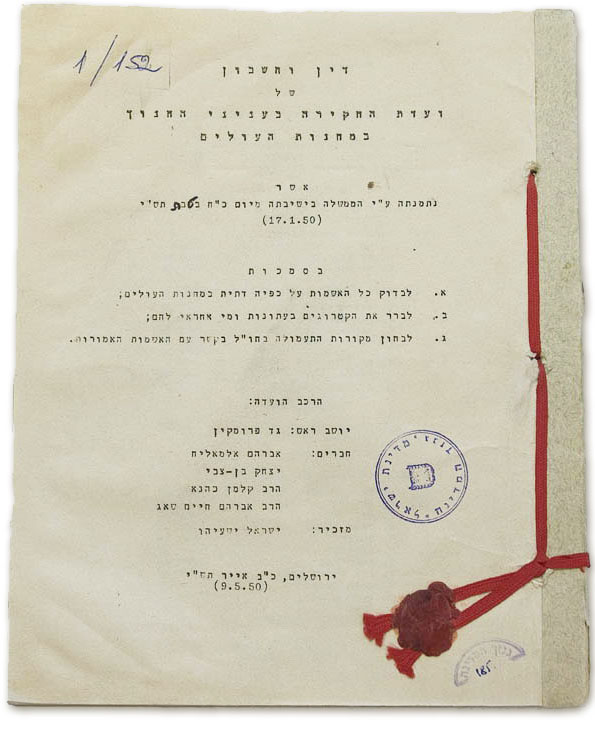

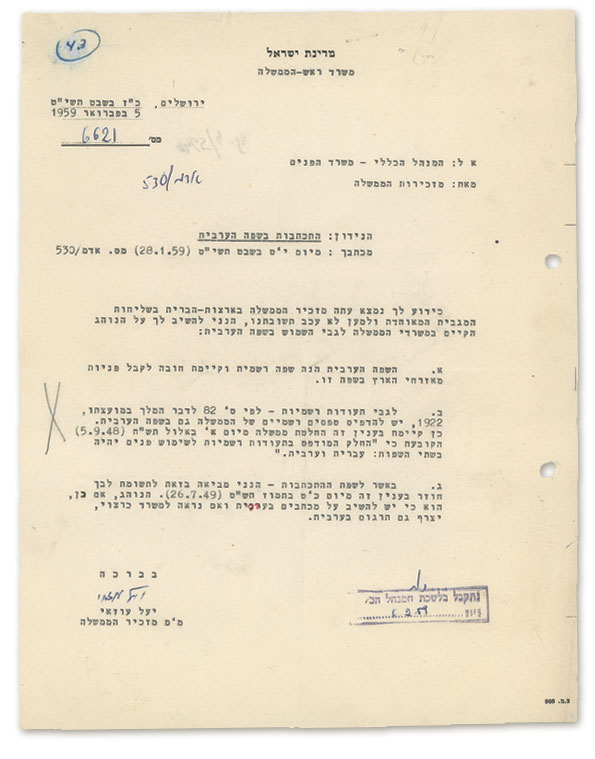

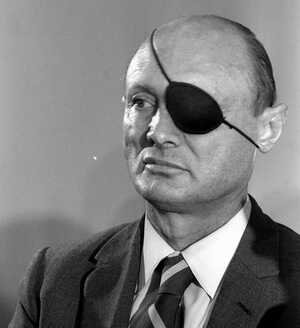

The question of the name of the State of Israel was not always so clear. At first, a number of proposals were made: such as the State of the Jews, the State of Israel, the State of Zion, the State of Judea, the Jewish State of Palestine and more. A committee consisting of three members of the Provisional Government submitted a reasoned opinion on how to call the state to be.