.1 | 23 October 1973: Fighting Continues Despite the Ceasefire, SC Resolution 339

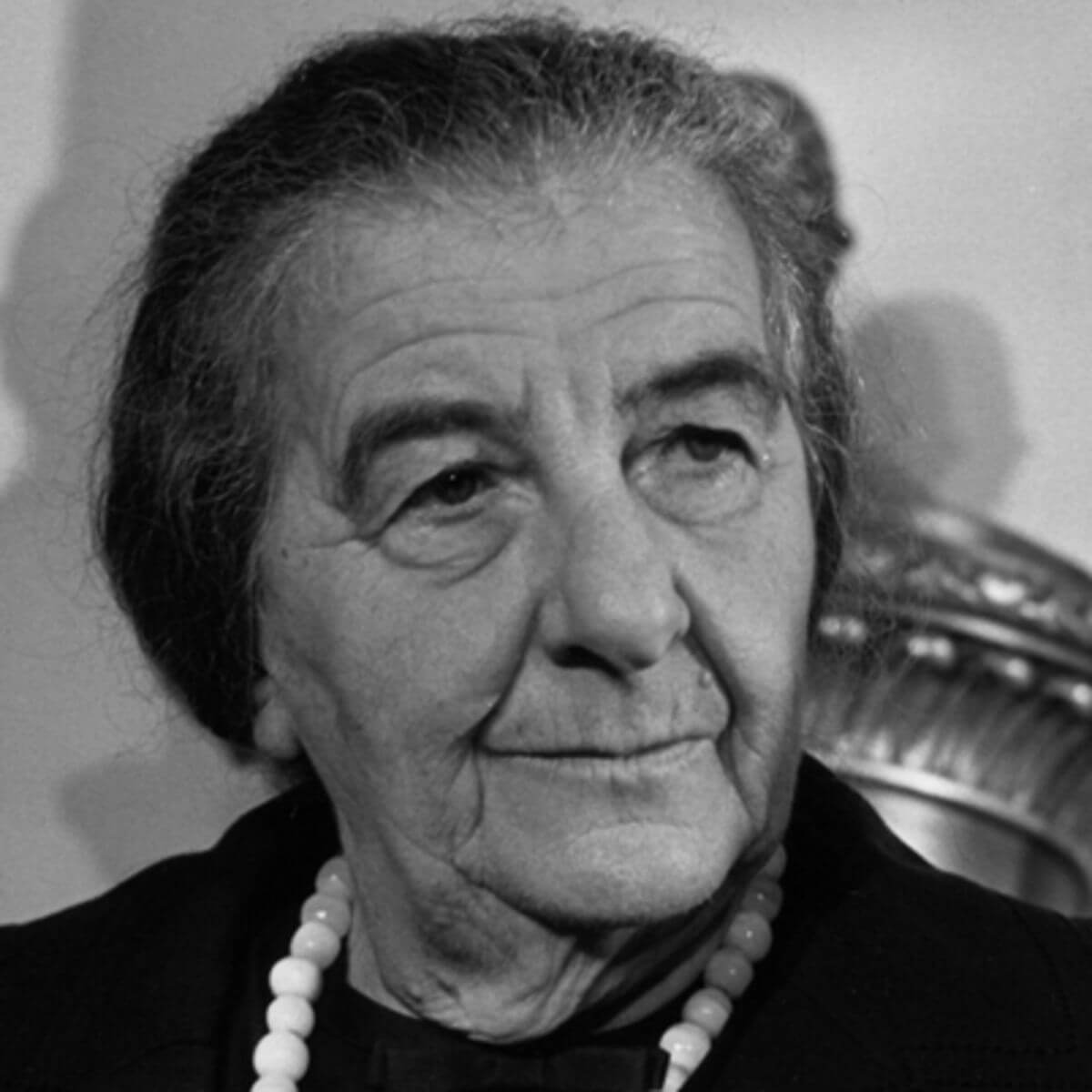

On 23 October there were no cabinet or government meetings, and the leaders’ activities were documented only in the bureau journal, which shows that despite the ceasefire, fighting continued on both fronts. The IDF commanders were eager to take advantage of their success for additional achievements. During the morning Golda approved the bombing of a store of oil tanks not far from Damascus, as a preemptive action against a Syrian attack. Elazar wanted to drag out the fighting on the southern front for two more days in order to complete the encirclement of the Egyptian Third Army, which was on the eastern side of the Suez Canal in the southern sector, opposite the Mitla and Jiddi Passes, and he sent Bar-Lev to persuade the prime minister.

Bar-Lev met with Golda in Tel Aviv and expressed surprise that pressure was being exerted on the IDF to end the fighting. In fact he wondered why Israel had accepted the ceasefire while the IDF was in full momentum. After he heard why Israel had agreed to the US demands, Bar-Lev explained the difficulties of stopping at the present stage. The IDF was deployed in long lines which would be hard to defend against a huge army, and before the Egyptians had suffered a decisive blow. “From this war they must reach the conclusion that nothing can help, that they cannot destroy Israel”, he said. Bar-Lev wanted her to approve several more days of fighting to complete the encirclement. The prime minister agreed and gave the high command freedom of action to improve its positions on the southern front.

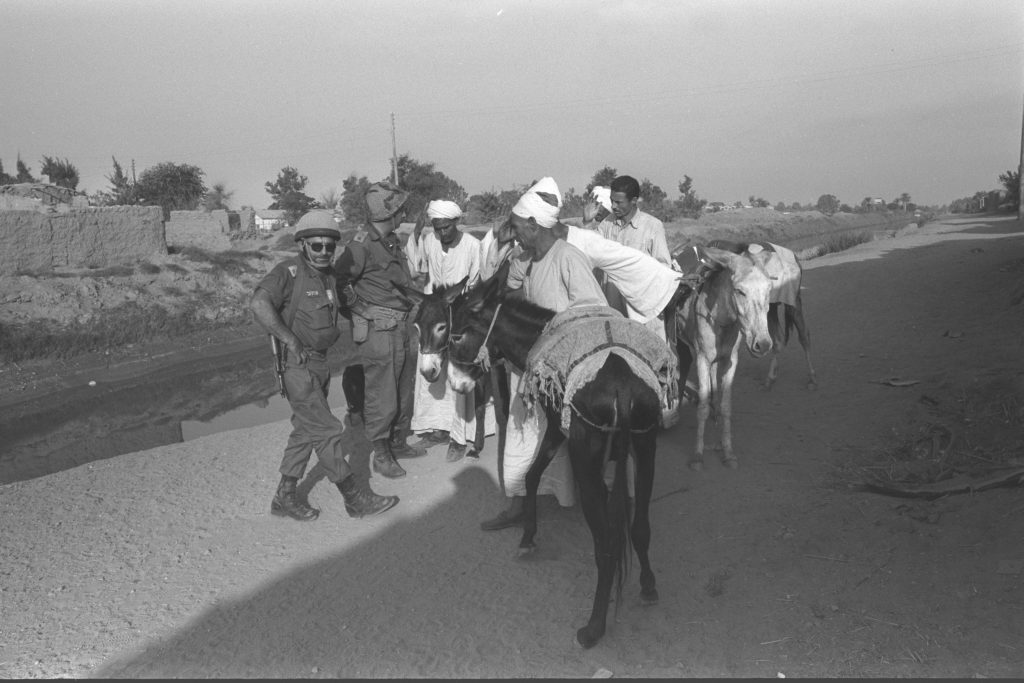

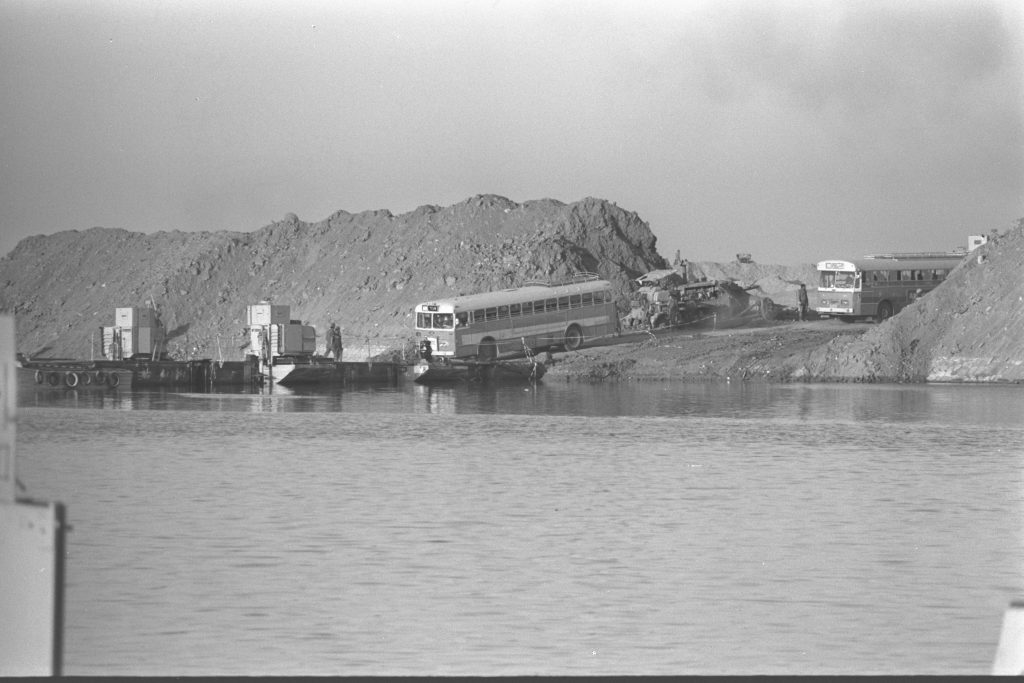

Civilian buses carrying reinforcements across the Suez Canal, 23 October 1973. Photograph: Avraham Kugel, GPO

At 18:03 the prime minister made an announcement to the Knesset, in the presence of the president, on the government’s decision to accept Security Council Resolution 338. As for the military situation, she said that on the Syrian front Israel was positioned along better lines than those of 6 October; and on the Egyptian front, although the Egyptians had achieved some successes, the IDF’s breakthrough to the western bank of the Suez Canal provided Israel with great advantages and neutralized the Egyptian threat. She emphasized that “we agreed to the ceasefire not out of weakness, but at the height of military initiatives and momentum” (See: the statement in the Knesset). Now that the war was officially over, the restraint that the opposition adopted while the fighting was going on came to an end, and the government’s decision was bitterly criticized by its spokesmen.

Later that day the IDF forces swept into the southern part of the area west of the Suez Canal and reached the outskirts of the city of Suez. Thus, the IDF cut off the Egyptian Third Army from its supply sources, and the Israeli forces were deployed on the Cairo-Suez road at the 101 kilometre mark. The continued fighting and the Israeli military successes enraged the USSR, and the Americans were not happy either. For fear of the collapse of the US position in the Arab world, and a confrontation with the Soviets, Kissinger decided to halt the Israeli offensive. He approached the secretary-general of the UN and the Soviets with a proposal to draft another Security Council resolution calling on all the parties to observe the ceasefire and accept a delegation of observers to supervise its implementation. Israel, for its part, made every effort to convince the Americans that its military movements were a reaction to violations of the ceasefire agreement by the Arabs (See: Telegrams Nos. VL/2, LV/252). The Soviets, for their part, exerted heavy pressure, hinting that the US was cooperating with Israel, and worked for an immediate meeting of the Security Council to pass an additional resolution, with a demand to the fighting parties to return to the positions they were in when the ceasefire resolution was passed, which was, of course, aimed at Israel. Israel vehemently objected, but Kissinger told Dinitz that the US could not oppose it and would not veto the resolution, although it would make it clear that the implementation of the withdrawal was not practical (See: Telegrams Nos. LV/256, 257). Soon afterwards Kissinger demanded, in Nixon’s name, that Israel stop firing immediately, or at least stop its offensive (See: Telegram No. LV/258).

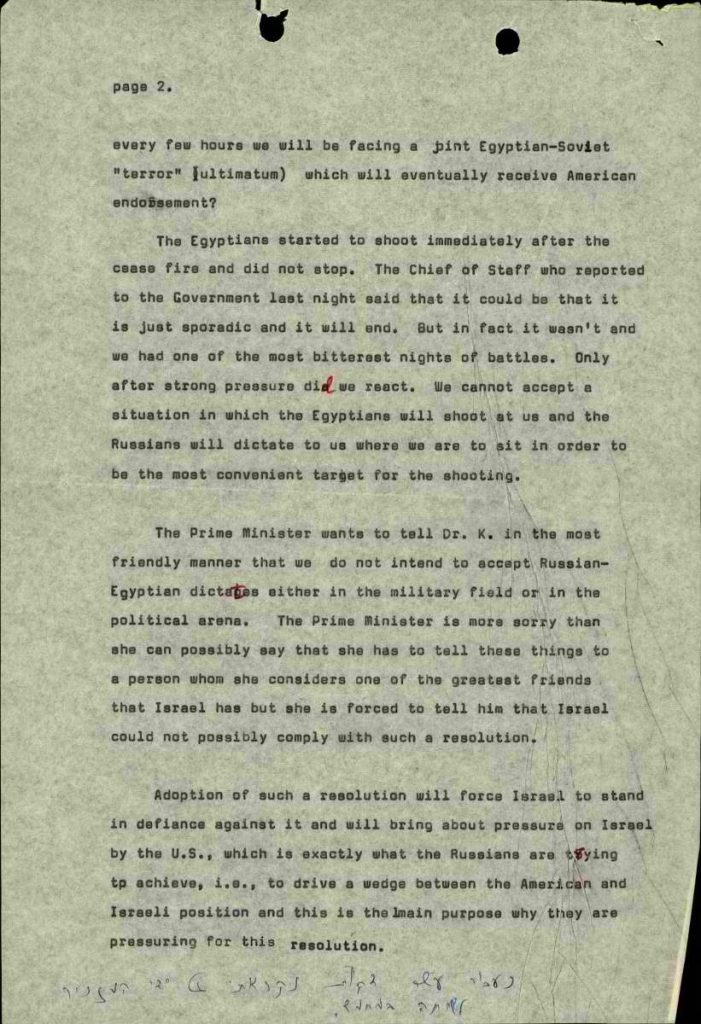

This new development, and the bitter experience of the last few days, set off alarm bells in Israel. It feared that an pattern was developing, in which the Egyptians and the Soviets would decide on steps convenient for them, and after the latter had obtained US agreement, Israel would find itself again and again confronted by dictates putting it in an unfavourable position. Golda told Dinitz in a telephone conversation to transmit a message to Kissinger that was polite but very firm. She made it clear why Israel could not agree to this behaviour, and therefore could not agree to pull back its forces to the lines of 22 October (See: Telegram No. LV/259).

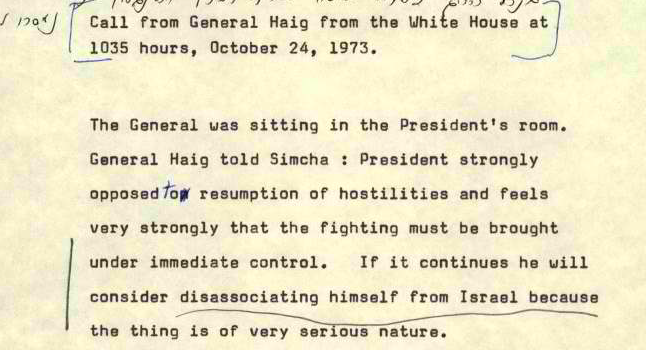

Extract from Golda’s message to Kissinger, 23 October 1973. File A 4996/5

The harsh tone of the message attests to the crisis of confidence that developed after the secretary’s trip to Moscow and his actions there. Kissinger sensed this and made every effort to soften the picture. In his talk with Dinitz and Shalev, and in a private meeting with Dinitz, he repeated that things could have been much worse for Israel were it not for his intervention. He spoke with warmth about his visit to Israel, and his emotions at “meeting with the people in Israel; he felt that he’d met with a great nation”. He explained that the resolution resulted from US interests, which would ultimately also serve Israel. Kissinger reminded them of his support for continuing the Israeli attack, and claimed that the resolution had no practical significance since he did not expect Israel to return to the 22 October lines, but at most to make some small territorial gesture (See: Telegrams Nos. LV/260, 261). However, Golda rejected this proposal, and promised “that if the Egyptians stop firing, we will too” (See: Telegram No. LV/264).

On 23 October the Security Council adopted an additional resolution, Resolution 339, calling for a ceasefire, which included a demand for the immediate return of the forces to their positions on 22 October, and the dispatch of observers to the fighting zone to supervise its observance.